|

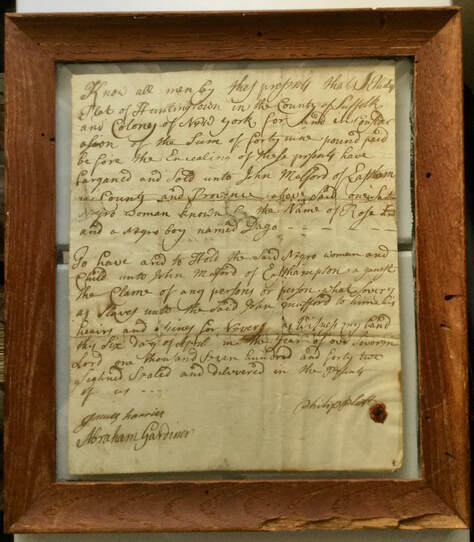

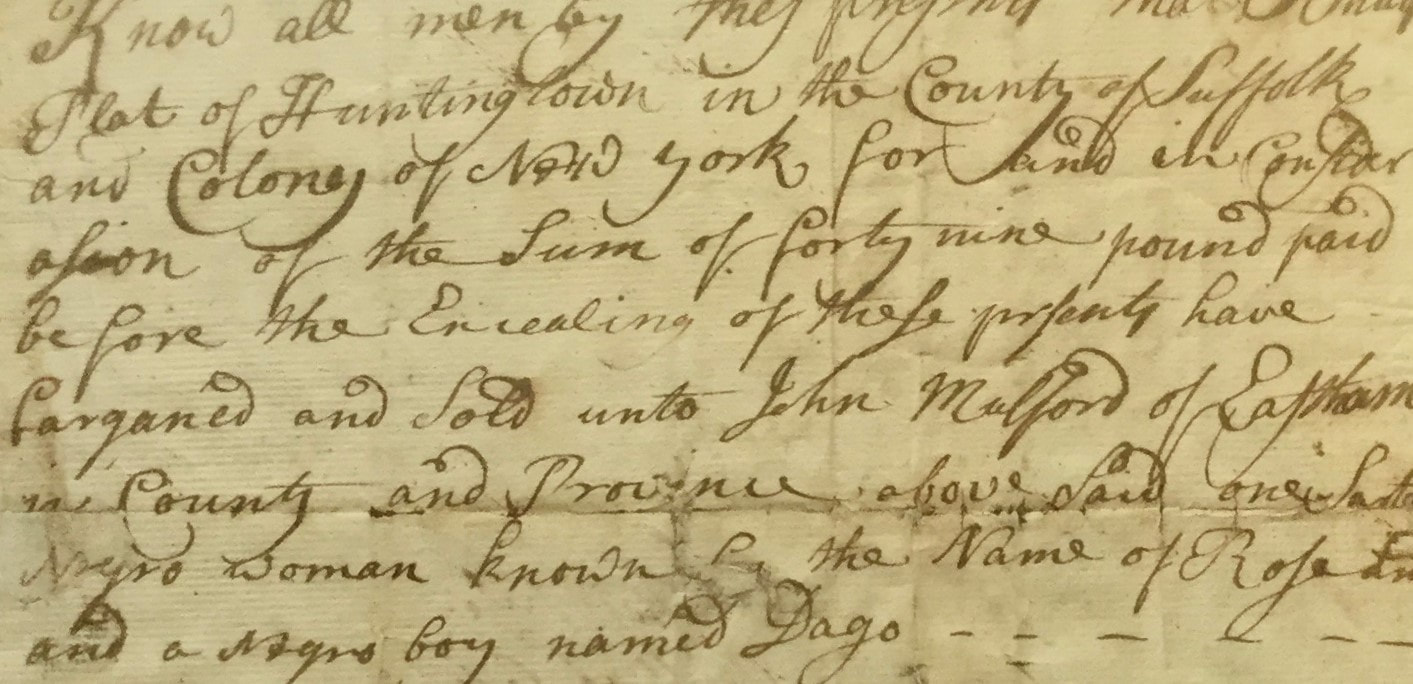

It is a common misconception that slavery was rare in New York state. According to The Long Island Museum's 2019 exhibit "Long Road to Freedom: Surviving Slavery on Long Island," in 1749 14% of the population of Suffolk County was comprised of enslaved persons. The first U.S. Census, conducted in 1790, records approximately 3,260 people living in the Town of Huntington, of which 221 were enslaved, and 74 were free people of color. The document pictured here, just acquired by the Huntington Historical Society, is a transactional record of the sale of two enslaved persons by Philip Platt of Huntington to John Mulford in "Easthampton." Document Transcription

(Please note: This is a direct transcription and includes errors or variations in spelling. Blanks denote a word that is indecipherable.) Know all men by thes presents that I Philip Plat of Huntingtown in the County of Suffolk and Colony of New York for and in consideration of the sum of forty nine pound paid before the ensealing of these present have bargained and sold unto John Mulford of Easthampton in County and Province above said one ______ Negro woman known by the name of Rosean and a negro boy named Dago. To have and to hold the said Negro woman and child unto John Mulford of Easthampton a ganest the claim of any persons or person whatsoever as slaves unto the said John Mulford to him, his heirs and __________ for ever. As witness my hand this sixth day of April in the year of our Sovereign Lord one thousand seven hundred and forty two signed sealed and delivered in the presence of us James Harries Philip Platt Abraham Gardiner

0 Comments

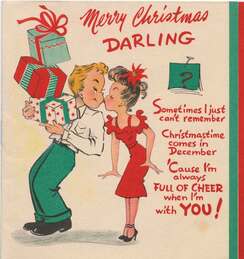

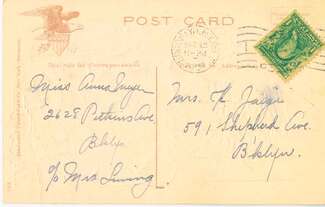

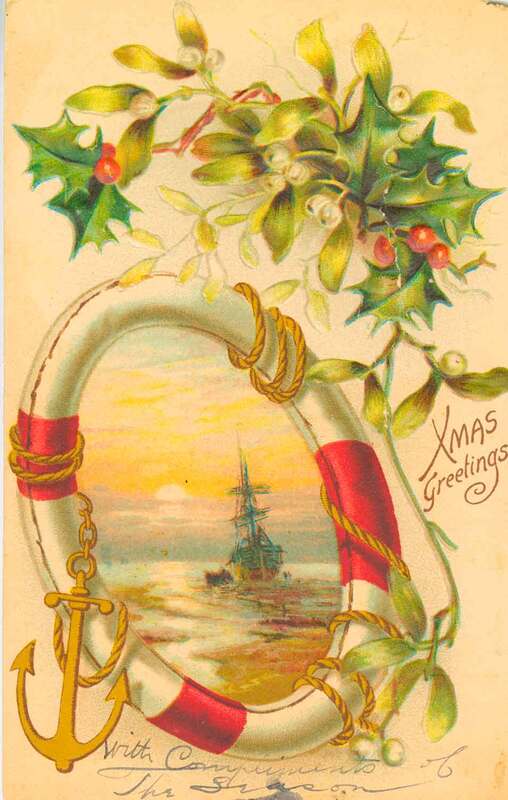

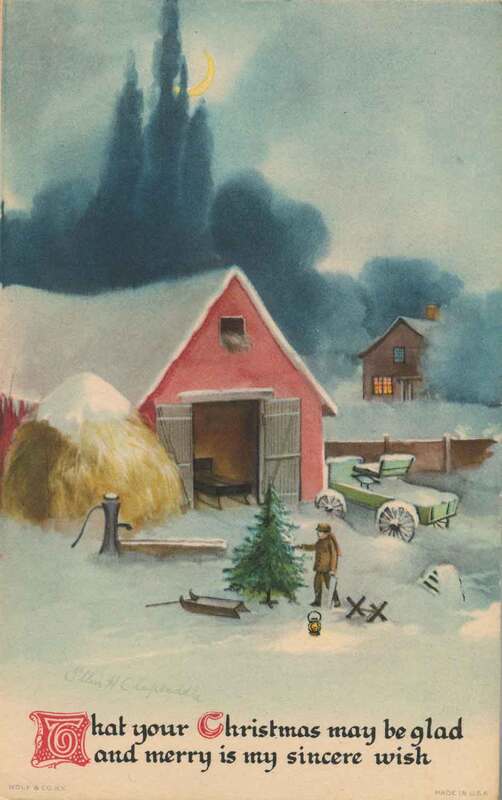

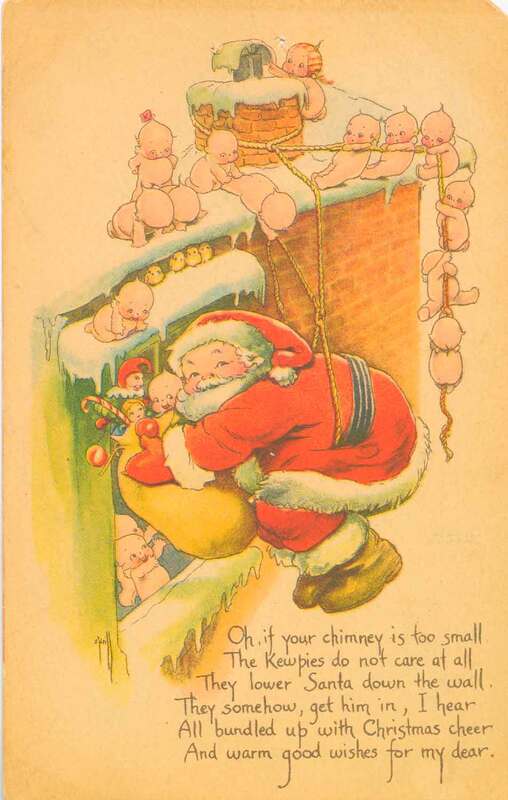

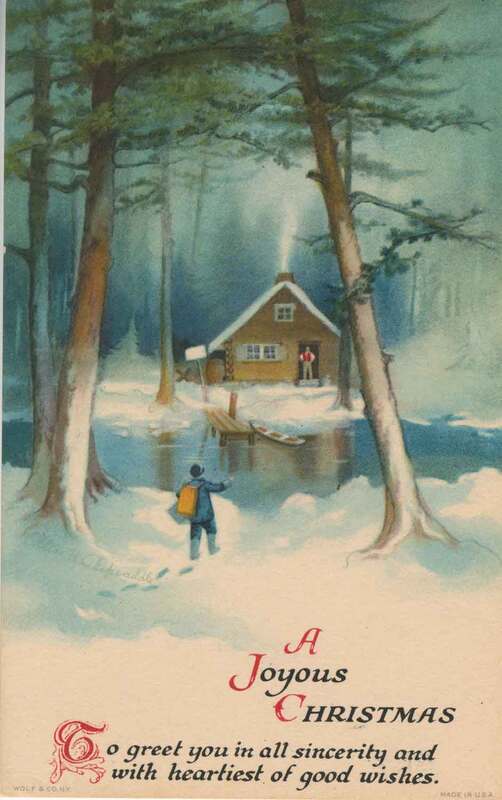

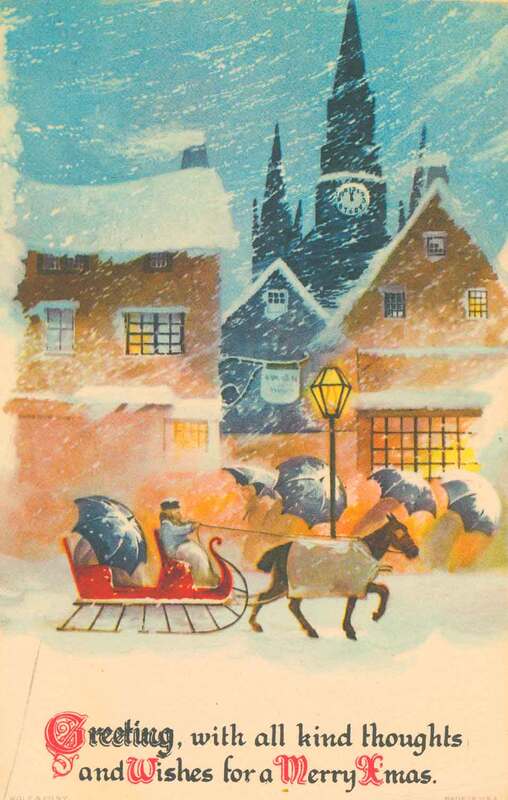

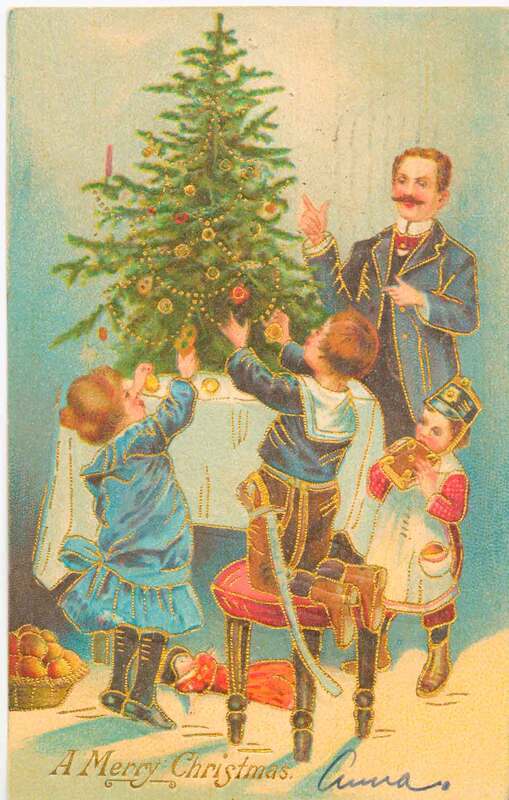

What is Ephemera? Typically made of paper, ephemera is the name given to collectible memorabilia that was intended for one-time or short term use. Examples include ticket stubs, political flyers, advertisements, maps, invitations, and greeting cards. We're excited to share these examples of holiday ephemera, hand picked by our archives team from The Huntington Historical Society's collection. Dated 1950, this fold-out holiday card was designed by George Earl Buzza, a commercial artist who opened his own greeting card company. Holiday cards in the 1950s frequently featured family-oriented and lighthearted motifs. First Christmas Cards The Christmas card tradition began in England in the 1840s when socialite Henry Cole found answering his stack of holiday mail a daunting task. Therefore, he asked his artist friend, J.C. Horsley, to design and print holiday cards with a salutation. By the end of the century, printed holiday greetings were commonplace in Britain and the United States. Christmas cards were imported from England and Germany to America until 1874, when printer and lithographer Louis Prang printed the first American holiday greeting cards in Roxbury, Massachusetts. Initially the cards were scenes of woods and nature, but over the years, he included images of Santa and Christmas trees. By the 1880s, he printed about 5 million Christmas cards annually. Christmas Postcards The U.S. Post Office was the only agency allowed to print and produce postcards until 1898, when congress passed the Private Mailing Card Act allowing publishers to produce cards for mailing by individuals. It was stipulated that the back could not be divided into space for both address and message. In 1907, the Post Office allowed postcards with a divided back, where the message was written on one side and the address on another. This is one way to date early postcards that don't have a dated postmark! Do you see a name written under the stairs on the left side? This signature belongs to Ellen Clapsaddle, one of the most prolific illustrators of the late 1800s and early 1900s. She was one of very few working female illustrators/commercial artists, and her designs, usually featuring children, were and remain popular and highly collectible. Click the images below to see vintage Christmas cards from our ephemera collection! From all of us at The Huntington Historical Society, we wish you a very happy holiday! The Huntington Historical Society is dedicated to preserving and sharing the history of the Town of Huntington. Please help us continue this work by making a donation!

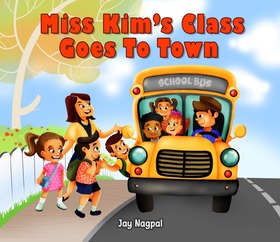

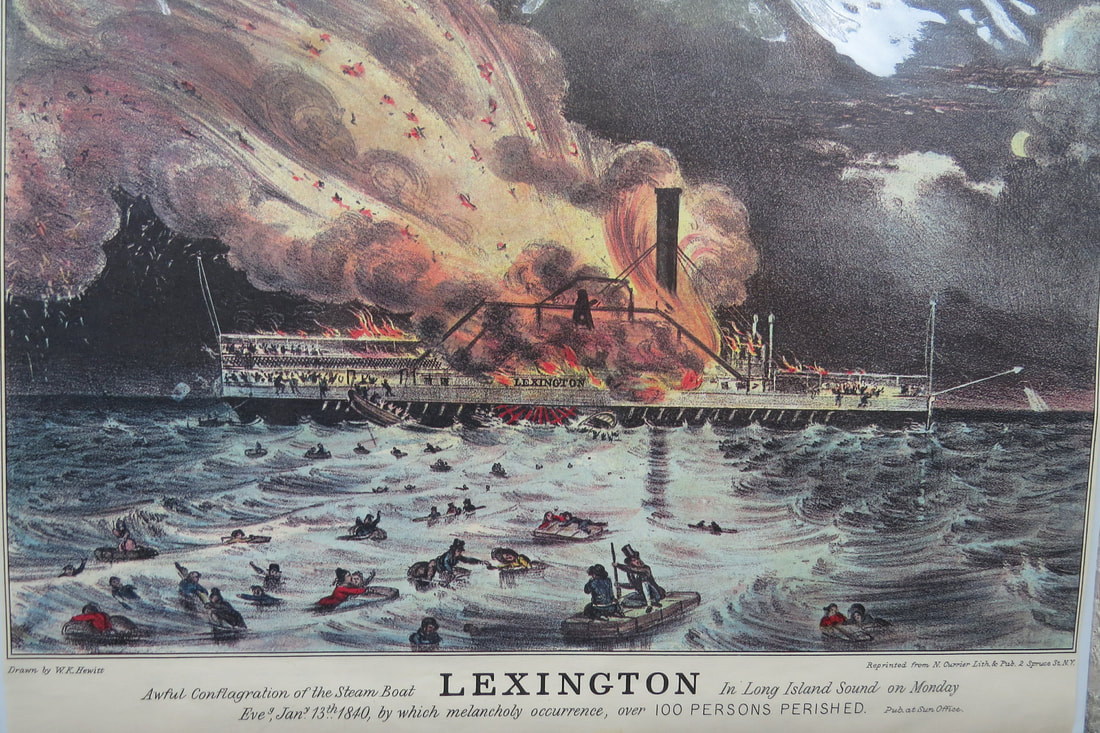

The Huntington Historical Society is excited to announce a new children's book about the Town of Huntington's historic sites. Miss Kim’s Class Goes To Town is a glimpse into the rich history of the Town of Huntington written by a local high school senior, in order to spark curiosity and foster a love of history in young minds. Readers of all ages will enjoy following Miss Kim’s class on a field trip to the historic sites of Huntington. The class is guided by Mr. Robert, the Town Historian, who is inspired by Town Historian, Robert Hughes. The students, who suspect the day will be a drag, find themselves thoroughly fascinated and surprised by the wonderful history that surrounds them. The book's publication is sponsored by People's United Bank and will go on sale just in time for the holidays. All are welcome to join us at the Huntington Branch (182 East Main Street) of People's United Bank for a book launch and meet and greet with the author. Stop by the branch on Saturday, November 30th between 1pm–3pm to meet Jay and pick up your copy!  About the Author: Jay Nagpal is a senior at Half Hollow Hills High School East in Dix Hills, New York. He is deeply passionate about history and founded the Dix Hills-Melville Historical Association. He has written several historical research papers. One of his papers was published in The Concord Review and his writing has been featured in Teen Ink magazine. He was also awarded first place at the regional National History Day competition. Jay has received recognition from his school district’s Board of Education for his dedication to raising awareness of local history. He is also a recipient of the 2019 Brown University Book Award. In addition, Jay is engaged in sustainability research at Stony Brook University. By William H. FrohlichHuntington Historical Society Board Member Currier & Ives first big selling lithograph in 1840. The Lexington was a paddlewheel steamboat that operated in the Long Island Sound between 1835 and 1840. It was commissioned by Cornelius Vanderbilt, and was considered one of the most luxurious steamers in operation at 220 feet in length. It began service between New York City and Providence, Rhode Island. But in 1837, the Lexington switched to the route between New York and Stonington, Connecticut, to connect with the newly built Old Colony railroad to Boston. You might remember that this was the same time that the Long Island Railroad was building the main line to bring people to Greenport. There, they would board the ferry to Stonington and get on the new train to Boston. The Long Island Railroad claimed that this rail-boat-rail route would cut the steamer journey from New York City to Boston from 16 hours to 11. The Lexington was the fastest steamer on Sound, at the time, in effect competing with the LIRR! It is important to note that the Lexington was not aloud to leave the Sound and enter open ocean, so it couldn’t go all the way to Boston. And, it didn’t have staterooms for overnight guests. On the night of January 13th, 1840, midway through the ship's voyage through the Sound, the casing around the ship's smokestack caught fire. Unfortunately, it igniting nearly 150 bales of cotton that were stored on deck aft of the smokestacks! (Bad idea!) The resulting fire was impossible to extinguish, and order was given to abandon ship. The ships' overcrowded lifeboats sank almost immediately, leaving the ship's passengers and crew to drown in the freezing water. Rescue attempts were virtually impossible due to the rough water, lack of visibility, the frigid cold and the wind. Of the 143 people on board the Lexington that night, only 4 survived, clinging to large bales of cotton that had been thrown overboard as makeshift life rafts. The ship's usual captain, Jacob Vanderbilt (the Commodore’s brother), was sick and couldn’t make the trip, and was replaced by veteran Captain George Child. The ship was four miles off Eaton's Neck when the fire started. With the ship's paddlewheel still churning at full speed, crewmen couldn’t reach the engine room to shut off the boilers. Once it was apparent that the fire could not be put out, the ship's three lifeboats were lowered. The first boat was sucked into the paddlewheel, killing all. Captain Child had fallen into that lifeboat and was among those killed. The ropes used to lower the other two boats were cut, causing the boats to hit the water stern-first and they sank immediately. Pilot Stephen Manchester turned the ship toward the shore in hopes of beaching it. But, the drive-rope that controlled the rudder quickly burned through, and the engine stopped 2 miles from shore. With the ship out of control, it drifted northeast and away from the land. The ship's cargo of cotton bales ignited quickly causing the fire to spread from the smokestack to the entire super-structure of the ship. Passengers and crew threw empty baggage containers and the bales of cotton into the water to use as rafts. The center of the main deck collapsed shortly after 8 p.m. The fire had spread to such an extent that by midnight most of the passengers and crew were forced to jump into the frigid water. Those who had nothing to climb onto quickly succumbed to hypothermia. The ship was still burning when it finally sank at 3 a.m. in the middle of the sound. According to legend, poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was scheduled to travel on the Lexington's fatal voyage, but missed the boat. This was due to discussing with his publisher the merits of his recent poem, The Wreck of the Hesperus - a poem that, ironically, also included a ship sinking. The Lexington disaster was depicted in a celebrated colored lithograph by Currier and Ives, and was their first major-selling print. Of the 143 people on board the Lexington, only four survived: Three were rescued by the ship “Merchant,” but the last man, David Crowley, the Second Mate, drifted for 43 hours on a bale of cotton, coming ashore 50 miles east, at Baiting Hollow. Weak, dehydrated and suffering from exposure, he staggered a mile to the house of Matthias and Mary Hutchinson, and collapsed after knocking on their door. A doctor was immediately called, and once well enough, Crowley was taken to Riverhead, where he recovered. An inquest jury found a fatal flaw in the ship's design to be the primary cause of the fire. The ship's boilers were originally built to burn wood, but converted to burn coal in 1839. They found that conversion had not been properly completed. Not only did coal burn hotter than wood, but extra coal was burned on that night because of the bad weather and rough seas. Sparks from the over-heated smokestack set the stack's casing ablaze on the freight deck. And, that fire spread to the bales of cotton stored improperly on deck close to the stack. The jury found crewmen's mistakes and violation of safety regulations to be at fault. Hilliard testified that once crewmembers noticed the fire, they went below deck to check the engines before attempting to fight the blaze. The inquest jury believed that the fire could have been extinguished if the crew had acted immediately. Additionally, not all of the ship's fire buckets could be found during the fire. And, only about 20 of the passengers were able to locate life preservers. They also found that the crewmembers were careless in launching the lifeboats, all of which sank immediately. The sloop Improvement, then less than five miles from the burning ship, never came to the Lexington's rescue. Captain Tirrell said he was running on a schedule and didn’t attempt a rescue, because he didn’t want to miss high tide and be late. The public became furious at his excuse, and Tirrell was attacked by the press in the days following the disaster. Ultimately, the U.S. government in the wake of the tragedy passed no legislation. It wasn’t until the steamboat Henry Clay burned on the Hudson River 12 years later that new safety regulations were imposed. The Lexington fire remains Long Island Sound's worst disaster. Of the 143, on board 139 perished. An attempt was made to raise the Lexington in 1842, and then again in 1850. The ship was brought to the surface briefly, and a 30-pound mass of melted silver coins was recovered from the hull. $50,000 in cash was never found and likely had burned up. During the raising attempt, the chains supporting the hull snapped, and the ship broke apart into three pieces sinking back to the bottom of the Sound. Today, the Lexington sections lie in 140 feet of water off Old Field Point. There is allegedly still gold and silver onboard that has not been recovered. The silver recovered in 1842 is all that has ever been found to date. There was talk of salvaging the remains of the ship about 10 years ago, but nothing came of it. Where is the Lexington? Today the wreck lies broken up across the bottom in anywhere from 80 feet deep to 140 feet of water. The wreck is covered in wire from the various salvage operations, fishing line, and other wreckage. The bottom is very dark, cold, and extremely hazardous. The actual locations of the paddlewheel, bow and stern are known. Location of two section of the Lexington in Long Island Sound. Point 4 is the location of the paddlewheel & Point 3 is the location of the bow. They are still there after nearly 180 years. A copy of the inquest report that analyzes what happened and who was to blame. It also includes all the names and hometowns of those who perished.

Scroll through the images from the 2018 Garden Tour! The final slide on each location features a more in-depth description of that site. "Our English Garden”

When my wife, Donna and I purchased our home in 2000 our backyard had absolutely zero appeal. It had very minimal plantings and the lawn had more weeds than it had grass. I took this as an opportunity to express my creativity and develop a landscape that reflected our carefree and relaxed personalities. We both adore the outdoors and wanted to have a peaceful sanctuary that we could enjoy on a warm summer day. Growing up in England I always loved the look and feel of an English Cottage garden. I used that inspiration when I was creating the walled flower beds and pathways. My vision was to be able to walk through the pathways and discover a new type of flower or plant around every corner. I made sure to plant in every nook and cranny so there was always something of beauty to be seen. I even allow flowering weeds to accompany my plantings. There is something quite beautiful watching the controlled chaos of weeds growing in harmony within the garden. My latest addition to our English garden oasis was our chicken coop that I designed and built surrounded by a handmade fence. I knew that I wanted to build a fence that was unique, but that also felt that it belonged in a nature setting. I achieved this by using unfinished locust tree trunks in their natural shapes. Our backyard took some time and work to get it where we wanted it, but we couldn’t be happier with the result. We love sharing our space with family and friends and of course the curious neighbor! “Poetry in Thread” celebrates one of our most delicate and beautiful textiles. Our exhibit will introduce you to the history and technique of lace making from the 17th century to today. With almost 50 items on display in the Dr. Daniel Kissam House, you’ll see examples of beautiful hand and machine-made lace, many from the 19th century. We are particularly proud to have on display several fine pieces from a collection of Kissam family lace, which we recently acquired from the descendants of Dr. Kissam. There were sheep being sheared! There were “sheepy” crafts being done! There were games being played! There was music (and PLENTY of dancing too) There was food to be enjoyed! It was the Sheep to Shawl festival and it was terrific!

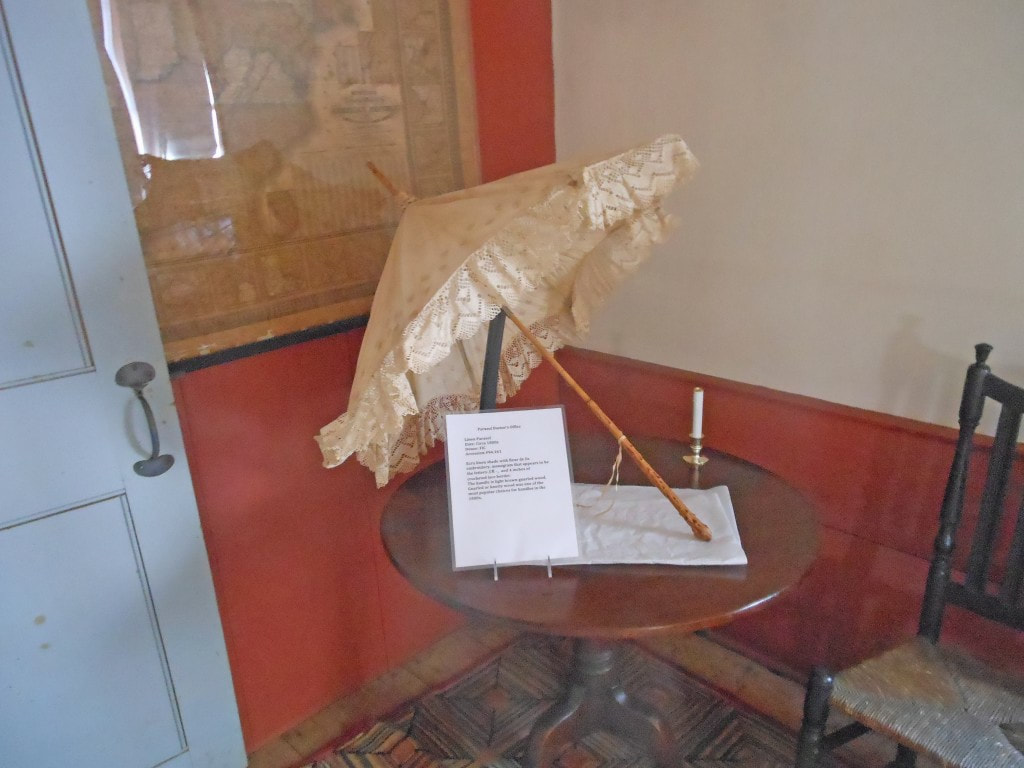

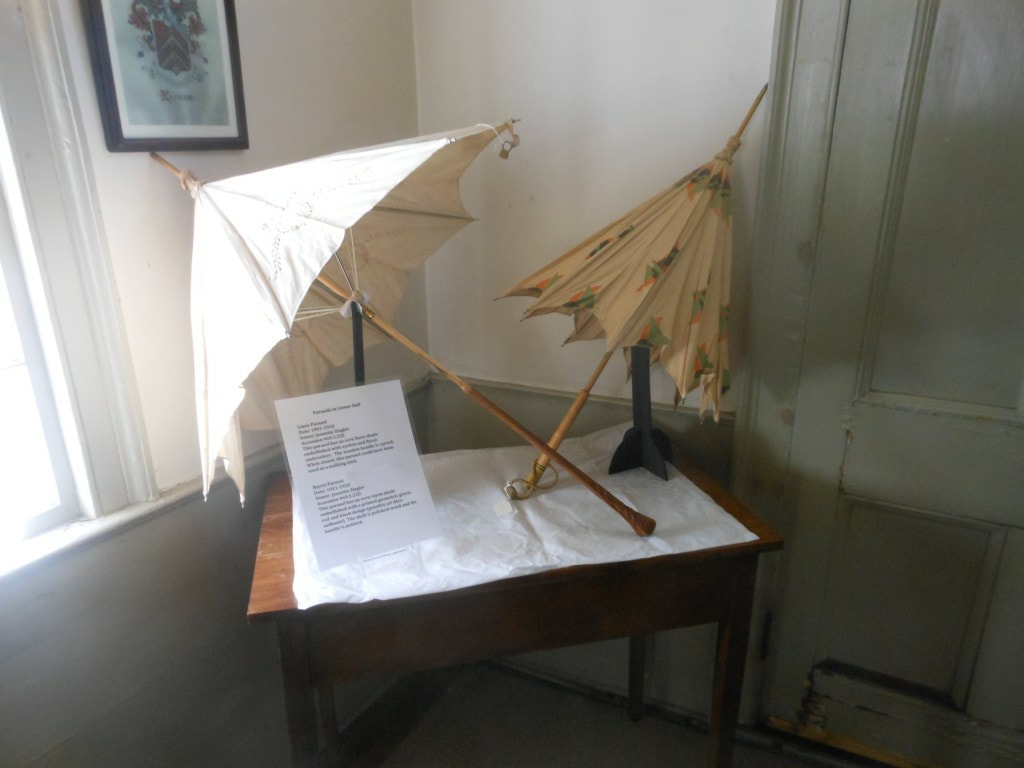

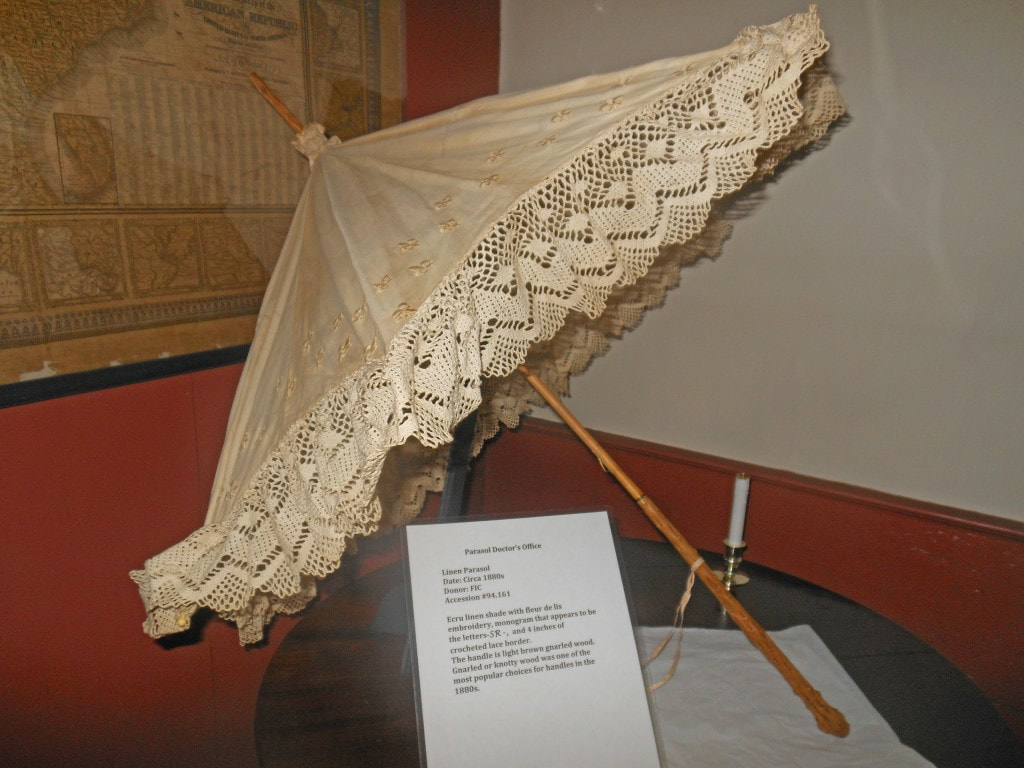

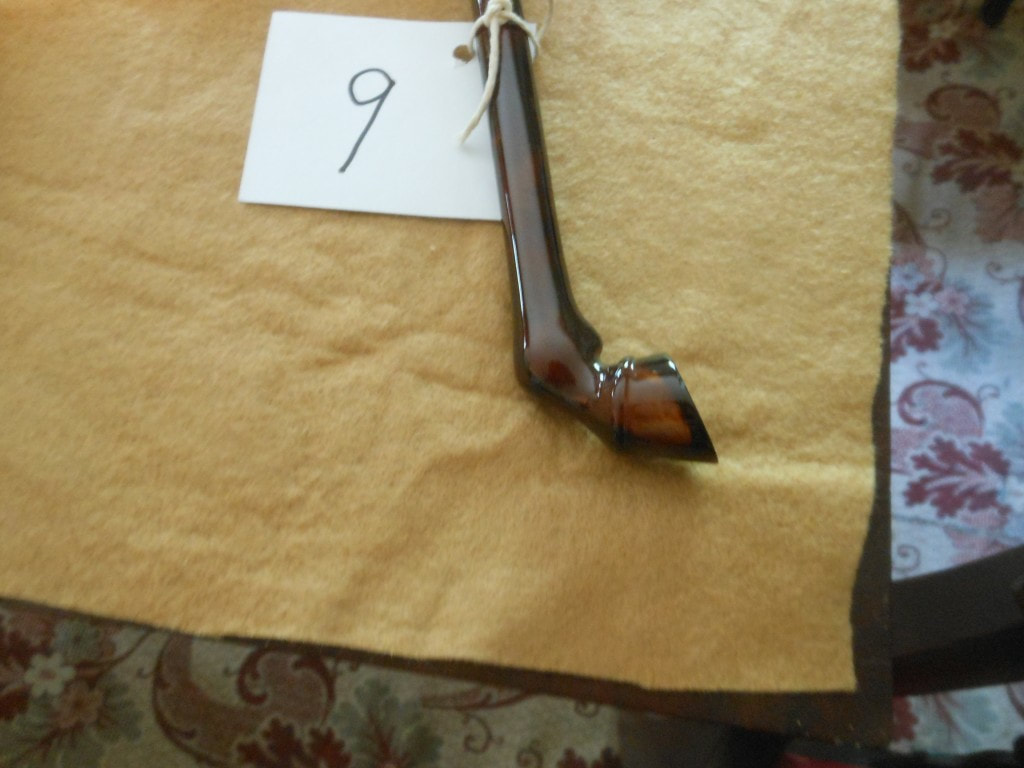

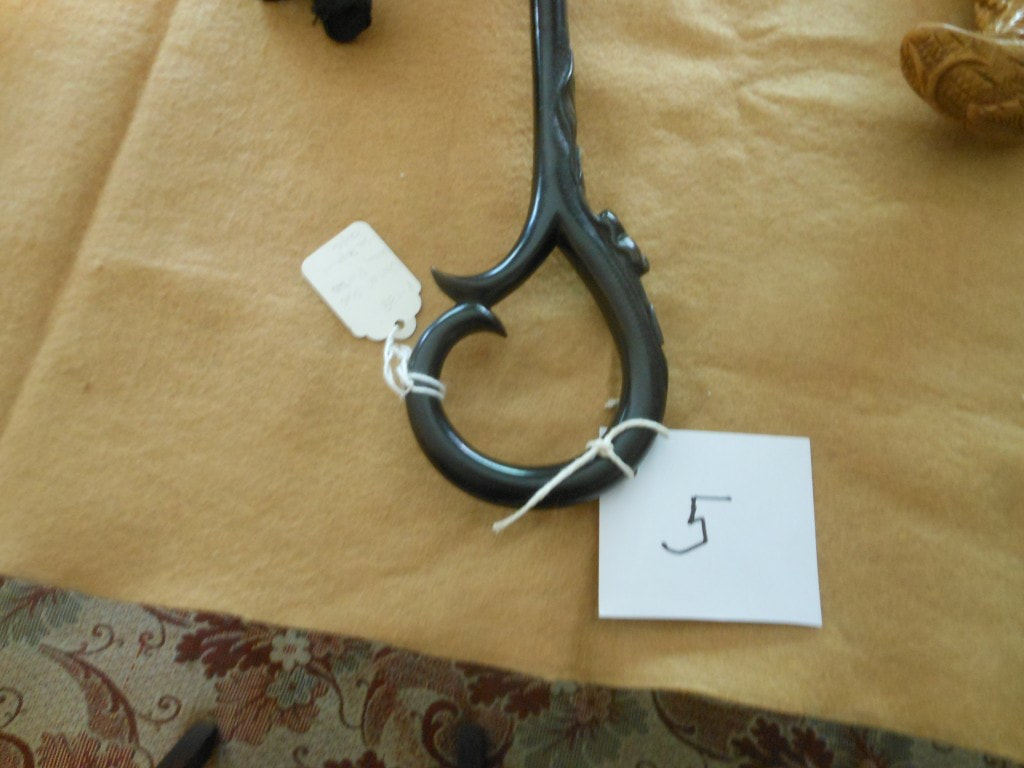

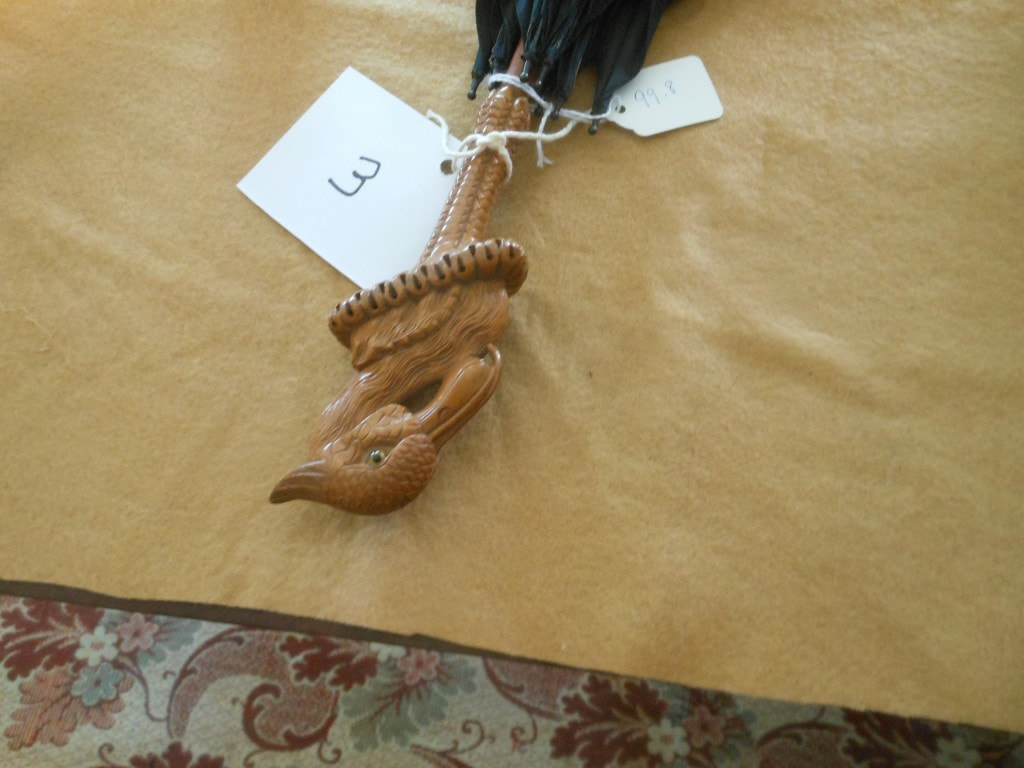

In this exhibit we featured three gowns that we consider being “jewels of our collection”. Additionally, we chose to highlight a seldom-displayed selection of antique parasols. These gowns beautifully fit into our title “promenade” which means to take a leisurely walk, ride, or drive in public,especially to meet or be seen by others. The “ladies” in our exhibit would have used parasols while wearing these gowns to promenade in the park or while riding in their carriages. A parasol is defined as a light, usually small umbrella Latin “umbra” (“shade”) carried as protection from the sun. The word parasol comes from the Latin words “parare” (“to shield”) and “sol” (“sun”). The history of parasols and umbrellas goes back thousands of years in Egypt, China and India where the use has been for protection from the sun and its heat. Only in the past few hundred years have umbrellas been used for rain protection. But it was during the Italian Renaissance of the 16th century that umbrellas and parasols were introduced to Europe. At first the umbrellas and parasols were large, used interchangeably and usually carried by a servant to protect the wealthy from rain and sun. In this exhibit our earliest parasols date to the 1860s and the others date to the early, mid and late Victorian era and through the 1930s.  The Exhibit “Wedding Days & Wedding Nights” provides a view of wedding attire from the late 1800’s through the 1950’s. In addition to the gowns and nightwear of the brides, there is some clothing for the men worn during the ceremonies. There are also photos of couples, brides and wedding parties from the period. The gowns reflect Wedding Advice from Ladies Home Journal, from March 1894: “There are some things that a bride must remember: her bodice must be high in the neck; her sleeves reach quite to the wrists, and her gown must be full, unbroken folds that show the richness of the material, and there must not be even a suggestion of such frivolities as frills or ribbons of any kind.” The Huntington Historical Society’s costume collection has an extensive selection of wonderful Bridal gowns dating back to 1839, as well as sleepwear from a variety of decades. The Ladies of the Attic, our costume collection committee, selected gowns for this exhibit to highlight fashion changes in vogue in the 19th and 20th centuries and matched them with their nightwear counterparts. Lovingly hand-made nightgowns transition to embellished silky sheer peignoirs. The result is a fun and informative look at the changing styles of brides over the decades and a peak at what they might have worn on their special night. Fashions in Wedding gowns, and weddings are constantly changing. In the early 1800’s, weddings were very solemn affairs held in a church. The bride wore a dress with a high neckline and long sleeves and was reminded she was attending a religious service and not a ball. Many brides married in their “Best Dress”, which would be of any color, including black or brown. Many married in their going-away dress, often practical traveling suits but specially trimmed for their wedding day. The bride would wear a bonnet or veil. Although not shown in the exhibit, there are many wedding dresses in the collections matching these descriptions. In two articles in the Long Islander (Huntington’s local newspaper started by Walt Whitman) describing weddings in 1879 and 1885, one bride wore dark blue silk, the other steel colored corded silk, the first married at precisely one o’clock, and took the afternoon train to the home of the groom in Brooklyn. The second, left the next day with her husband to their new home in Oyster Bay. Both weddings were held in their family homes. Queen Victoria’s wedding in 1840, was a marker which began the white wedding dress tradition. Her choice of plain white satin dress and an orange blossom wreath head-dress with lace veil was shockingly plain by royal standards. Although white had been worn for weddings earlier, the difficulty and expense of bleaching fabric made it available to only royalty or the wealthy. Godey’s Ladies Book, in 1860, published the first color spread of bridal costumes. In America, with its aristocracy of wealth, it soon became a trend to make all attempts to out dazzle one and other when it came to the brides trousseau. Veils were not worn over the face until the end of the 1860’s. In the 1890’s, “The Gay 90’s”, weddings in the home were favored. But by the turn of the century, 1901 to 1935 the white wedding dress tradition (influenced by Queen Victoria) was firmly established and the wedding gown was no longer meant to be worn for any other occasion. In 1920’s, with WW1 over and the world safe for democracy, women have the vote, there is a chicken in every pot, 2 cars in every garage. The spirit of irresponsible times carried over into weddings of the day. Informality, elopements, and a justice of the peace instead of a minister were becoming the norm. Gone were the days of many hallowed institutions along with the corseted figure bridal gowns. Now a girl could show her legs. Wedding dress styles continued to follow fashionable dress silhouettes and morphed into longer weddings that returned to the church.  A COLLECTION OF CLOTHING ITEMS DATING BACK TO EARLY 1700’S The Huntington Historical Society Costume collection contains thousands of clothing items, donated since the founding of the Society in 1903. The items range from the glorious to the mundane, from old to new, from excellent condition to poor, from hand made to machine made. Legislator Jon Cooper recently stopped by the Conklin House to see the results of his support to maintaining and displaying our Costume collection. The Huntington Historical Society Costume collection contains thousands of clothing items, donated since the founding of the Society in 1903. The items range from the glorious to the mundane, from old to new, from excellent condition to poor, from hand made to machine made.  The Huntington Historical Society Costume collection, which is stored in the attic of the Kissam House, is precious gem. The collection consists of a variety of clothing items collected over the last 100 years. The original items were donated to the Society, when it was formed following Huntington’s 250th anniversary celebration. The original dresses had been provided as a display at the celebration. After the celebration the ladies of the community, who had organized the affair, decided to start the Historical Society, and they kept the dresses to start the collection. The Costume collection consists of various types of clothing. There are women’s dresses, blouses, hats, shoes, gloves and shawls. There are marvelous gowns and simple day wear. There are men’s coats, pants, shoes and gloves. There are uniforms and official hats. There are innumerable everyday clothing items and many one-of-a-kind dress items. The Historical Society puts on several costume collection exhibits in the Kissam house and the Conklin House each year which provide the community a view of clothing from our past. |

AuthorThis blog has been written by various affiliates of the Huntington Historical Society. Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

Become a Member

Donate Today!

Signup For Our Newsletter

Thanks for signing up!

© Huntington Historical Society. All rights reserved.

The Huntington Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the Town of Huntington for its steadfast support.

The Huntington Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the Town of Huntington for its steadfast support.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed