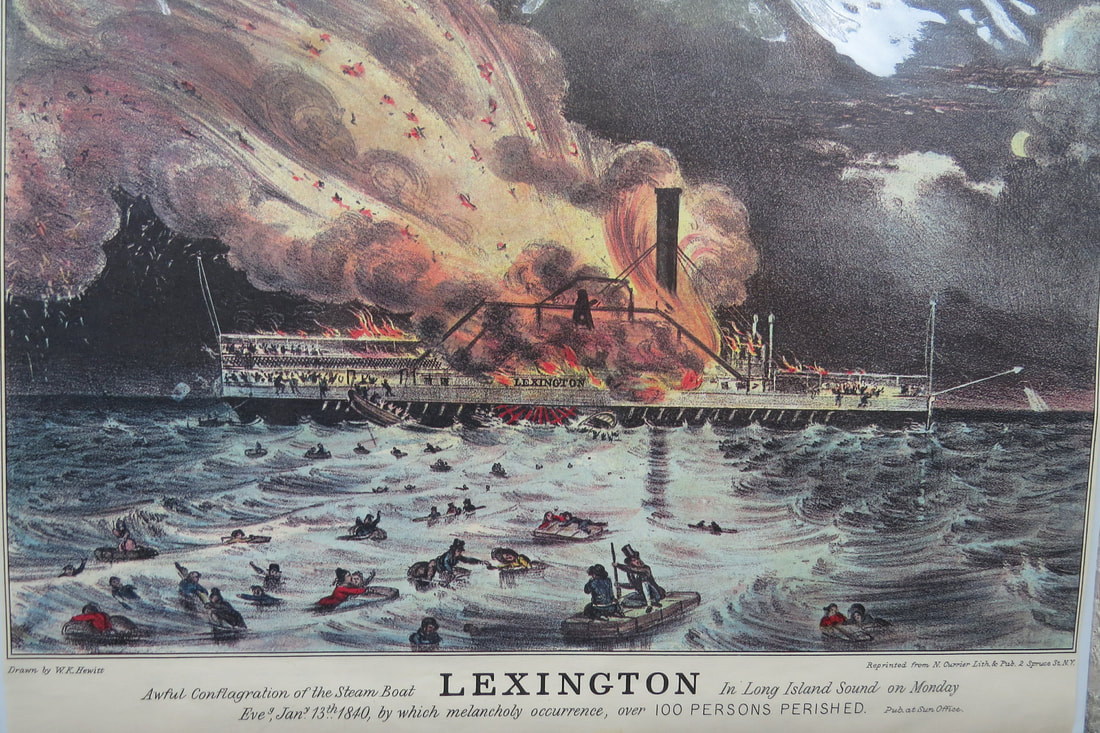

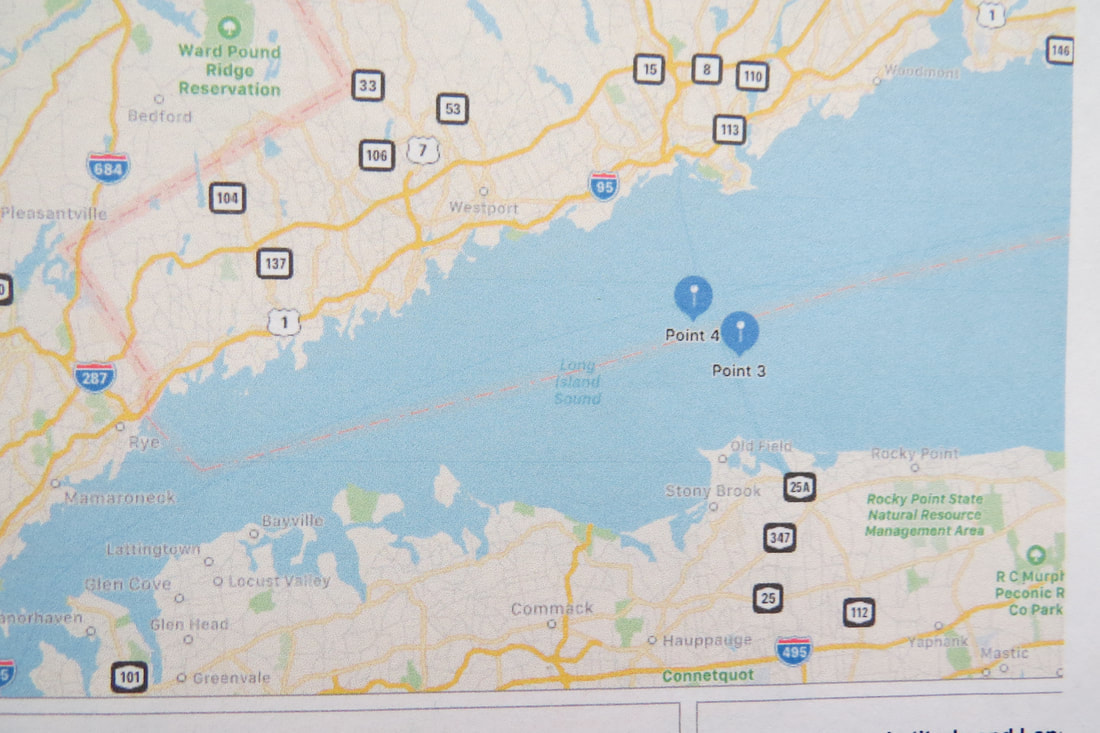

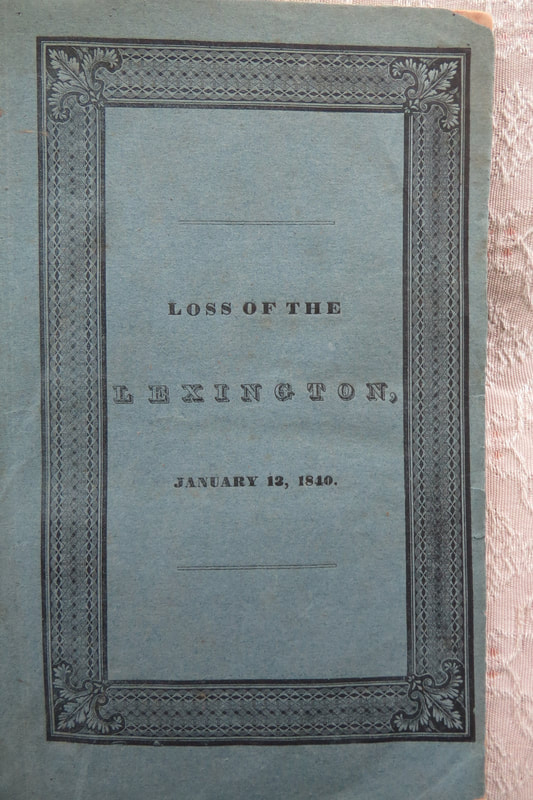

By William H. FrohlichHuntington Historical Society Board Member Currier & Ives first big selling lithograph in 1840. The Lexington was a paddlewheel steamboat that operated in the Long Island Sound between 1835 and 1840. It was commissioned by Cornelius Vanderbilt, and was considered one of the most luxurious steamers in operation at 220 feet in length. It began service between New York City and Providence, Rhode Island. But in 1837, the Lexington switched to the route between New York and Stonington, Connecticut, to connect with the newly built Old Colony railroad to Boston. You might remember that this was the same time that the Long Island Railroad was building the main line to bring people to Greenport. There, they would board the ferry to Stonington and get on the new train to Boston. The Long Island Railroad claimed that this rail-boat-rail route would cut the steamer journey from New York City to Boston from 16 hours to 11. The Lexington was the fastest steamer on Sound, at the time, in effect competing with the LIRR! It is important to note that the Lexington was not aloud to leave the Sound and enter open ocean, so it couldn’t go all the way to Boston. And, it didn’t have staterooms for overnight guests. On the night of January 13th, 1840, midway through the ship's voyage through the Sound, the casing around the ship's smokestack caught fire. Unfortunately, it igniting nearly 150 bales of cotton that were stored on deck aft of the smokestacks! (Bad idea!) The resulting fire was impossible to extinguish, and order was given to abandon ship. The ships' overcrowded lifeboats sank almost immediately, leaving the ship's passengers and crew to drown in the freezing water. Rescue attempts were virtually impossible due to the rough water, lack of visibility, the frigid cold and the wind. Of the 143 people on board the Lexington that night, only 4 survived, clinging to large bales of cotton that had been thrown overboard as makeshift life rafts. The ship's usual captain, Jacob Vanderbilt (the Commodore’s brother), was sick and couldn’t make the trip, and was replaced by veteran Captain George Child. The ship was four miles off Eaton's Neck when the fire started. With the ship's paddlewheel still churning at full speed, crewmen couldn’t reach the engine room to shut off the boilers. Once it was apparent that the fire could not be put out, the ship's three lifeboats were lowered. The first boat was sucked into the paddlewheel, killing all. Captain Child had fallen into that lifeboat and was among those killed. The ropes used to lower the other two boats were cut, causing the boats to hit the water stern-first and they sank immediately. Pilot Stephen Manchester turned the ship toward the shore in hopes of beaching it. But, the drive-rope that controlled the rudder quickly burned through, and the engine stopped 2 miles from shore. With the ship out of control, it drifted northeast and away from the land. The ship's cargo of cotton bales ignited quickly causing the fire to spread from the smokestack to the entire super-structure of the ship. Passengers and crew threw empty baggage containers and the bales of cotton into the water to use as rafts. The center of the main deck collapsed shortly after 8 p.m. The fire had spread to such an extent that by midnight most of the passengers and crew were forced to jump into the frigid water. Those who had nothing to climb onto quickly succumbed to hypothermia. The ship was still burning when it finally sank at 3 a.m. in the middle of the sound. According to legend, poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was scheduled to travel on the Lexington's fatal voyage, but missed the boat. This was due to discussing with his publisher the merits of his recent poem, The Wreck of the Hesperus - a poem that, ironically, also included a ship sinking. The Lexington disaster was depicted in a celebrated colored lithograph by Currier and Ives, and was their first major-selling print. Of the 143 people on board the Lexington, only four survived: Three were rescued by the ship “Merchant,” but the last man, David Crowley, the Second Mate, drifted for 43 hours on a bale of cotton, coming ashore 50 miles east, at Baiting Hollow. Weak, dehydrated and suffering from exposure, he staggered a mile to the house of Matthias and Mary Hutchinson, and collapsed after knocking on their door. A doctor was immediately called, and once well enough, Crowley was taken to Riverhead, where he recovered. An inquest jury found a fatal flaw in the ship's design to be the primary cause of the fire. The ship's boilers were originally built to burn wood, but converted to burn coal in 1839. They found that conversion had not been properly completed. Not only did coal burn hotter than wood, but extra coal was burned on that night because of the bad weather and rough seas. Sparks from the over-heated smokestack set the stack's casing ablaze on the freight deck. And, that fire spread to the bales of cotton stored improperly on deck close to the stack. The jury found crewmen's mistakes and violation of safety regulations to be at fault. Hilliard testified that once crewmembers noticed the fire, they went below deck to check the engines before attempting to fight the blaze. The inquest jury believed that the fire could have been extinguished if the crew had acted immediately. Additionally, not all of the ship's fire buckets could be found during the fire. And, only about 20 of the passengers were able to locate life preservers. They also found that the crewmembers were careless in launching the lifeboats, all of which sank immediately. The sloop Improvement, then less than five miles from the burning ship, never came to the Lexington's rescue. Captain Tirrell said he was running on a schedule and didn’t attempt a rescue, because he didn’t want to miss high tide and be late. The public became furious at his excuse, and Tirrell was attacked by the press in the days following the disaster. Ultimately, the U.S. government in the wake of the tragedy passed no legislation. It wasn’t until the steamboat Henry Clay burned on the Hudson River 12 years later that new safety regulations were imposed. The Lexington fire remains Long Island Sound's worst disaster. Of the 143, on board 139 perished. An attempt was made to raise the Lexington in 1842, and then again in 1850. The ship was brought to the surface briefly, and a 30-pound mass of melted silver coins was recovered from the hull. $50,000 in cash was never found and likely had burned up. During the raising attempt, the chains supporting the hull snapped, and the ship broke apart into three pieces sinking back to the bottom of the Sound. Today, the Lexington sections lie in 140 feet of water off Old Field Point. There is allegedly still gold and silver onboard that has not been recovered. The silver recovered in 1842 is all that has ever been found to date. There was talk of salvaging the remains of the ship about 10 years ago, but nothing came of it. Where is the Lexington? Today the wreck lies broken up across the bottom in anywhere from 80 feet deep to 140 feet of water. The wreck is covered in wire from the various salvage operations, fishing line, and other wreckage. The bottom is very dark, cold, and extremely hazardous. The actual locations of the paddlewheel, bow and stern are known. Location of two section of the Lexington in Long Island Sound. Point 4 is the location of the paddlewheel & Point 3 is the location of the bow. They are still there after nearly 180 years. A copy of the inquest report that analyzes what happened and who was to blame. It also includes all the names and hometowns of those who perished.

1 Comment

frederick h. terry

12/18/2023 08:32:16 pm

Deep within the headlands of the Terry Family Farm on Sound Avenue in Baiting Hollow lies Crowley Rock, a huge glacial erratic dubbed so by my great-grandfather Columbus Franklin Terry and subsequent progeny to mark the site of David Crowley’s shore landing amidst the “porridge ice” between a peninsula dubbed Negro Head by the British (Friars Head) and the now 4-H Eastern Camp. Crowley navigated up the woodlot road (which at the time extended to the beach!) and ended up at the Hutchingson farmhouse (approximately 500 yards and slightly West of Columbus Terry’s farmhouse on Sound Avenue. (still occupied by a Terry ancestor). Crowley suffered from severe frostbite and reportedly lost a few digits from the episode. The “Rock” is still celebrated in the family to this day. Professor Frederick H Terry Sr. 2023

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorThis blog has been written by various affiliates of the Huntington Historical Society. Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

Become a Member

Donate Today!

Signup For Our Newsletter

Thanks for signing up!

© Huntington Historical Society. All rights reserved.

The Huntington Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the Town of Huntington for its steadfast support.

The Huntington Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the Town of Huntington for its steadfast support.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed