By Emily WernerHHS Curator & Collections Manager In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, many professional weavers immigrated from Germany, Scotland, Ireland, or England after lengthy apprenticeships in specialized weaving techniques, such as damask or carpet weaving. Known as “fancy weavers,” they settled in small towns along the east coast, including New York, and adapted their specialized knowledge to weaving “bed carpets” or “carpet coverlets.”

Professional weavers were almost exclusively men. Although women continued to play a vital role in supporting textile production by preparing the raw materials and finishing the cloth after it was woven, few women actually became professional weavers themselves. Many professional weavers were not only weavers, but also worked other jobs, such as farming, to support themselves throughout the year. They set up workshops at home or at another established location, where customers could bring their design preferences and homespun yarn for the textiles they were commissioning. Professional weavers made coverlets for specific customers, typically women, and wove her name and the date into the corner block or along the border of the coverlet. Occasionally weavers included other phrases as well, such as their name, a town name, or even the name of the pattern. The text was almost always woven lengthwise into the coverlet (in the warp direction). Because of the reversibility of double cloth fabric, the text is legible on one side of the coverlet and appears reversed on the other. The practice of naming and dating coverlets in this manner is thought to have originated on Long Island. Long Island coverlets were woven in a weave structure called double cloth. Double cloth coverlets are created by weaving two layers of fabric simultaneously, each layer intersecting at specific points to produce the pattern. The fabric is reversible, with one side predominantly dark and the other side predominantly light. The dark yarn was indigo-dyed wool, usually provided by the customer, while the light yarn was undyed machine-spun cotton. Because they used twice as much yarn as other types of fabrics and required great skill and technology to weave, double cloth coverlets were some of the most costly and prized textiles in nineteenth-century American homes. Visit our new exhibit, From Farm to Fabric: Early Woven Textiles of Long Island, to find out even more about these beautiful textiles! Open through September 17, 2023 at the Soldiers & Sailors Memorial Building at 228 Main Street, Huntington. This exhibit was part of a collaboration with Preservation Long Island to highlight the importance of Long Island’s early weaving practices and industry. Their exhibit, Blanket Statements: Long Island’s Early Weaving Industry, explores Long Island’s early textile industry and the broader historical events that shaped its growth during the first half of the nineteenth century. Open through October 8, 2023 at the Preservation Long Island Gallery at 161 Main Street, Cold Spring Harbor. Photo captions: Geometric double cloth coverlet, woven for Phebe Titus, December 21, 1817. Attributed to Mott Mill. Huntington Historical Society, 1987.20 / Figured and Fancy double cloth coverlet, woven for Mary H. Wood, 1839. Huntington Historical Society, 1966.7.1.

0 Comments

By Barbara LaMonicaAssistant Archivist

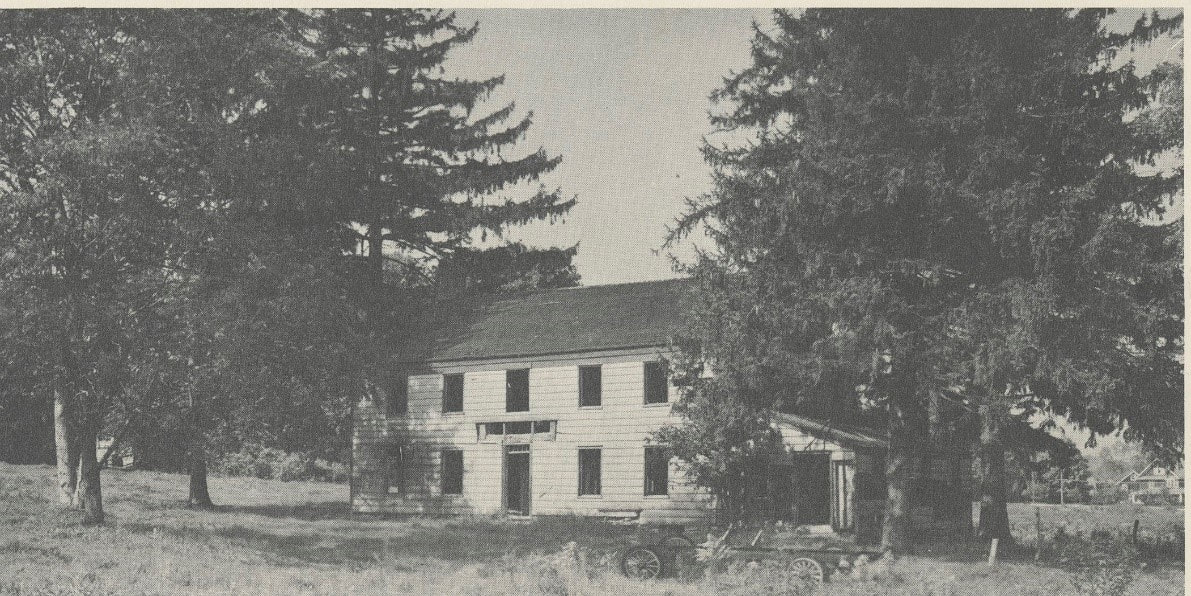

This law addressed the gap in care of the poor created by Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries, as the monasteries had been the main source of charity. The Elizabethan law established the precept of local control, meaning each village had the responsibility for its own poor. Local officials had the power to raise taxes and appoint an overseer to administer the charity funds. A later law, The Law of Settlement and Removal, empowered villages to expel persons back to their home village should they become dependent, insuring that “no vagabonds or beggars allowed. “ As early as 1687, the Province of New York passed a law mandating towns and counties take care of their own poor. Pre and post revolution New York continued to establish statutes such as binding out poor children as apprentices and servants, and the establishment of poor or work houses. Eventually children were removed from these institutions and placed in orphanages. According to Huntington Town Records, the town trustees who acted as overseers evaluated destitute residents on a case-to-case basis. Eventually separate overseers were appointed. These individuals came from prominent Huntington families. Town overseer records show in 1763 the first overseers came from the Brush, Platt, and Wood families. Over the years such personages as William Woodhull, Solomon Ketchum, John Rogers, Israel Scudder, Hiram Baylis served multiple terms. As an interesting aside, it was not until 1921 that the first woman overseer, Maude E. Henschell, was elected. A Brooklyn Times Union article dated December 29, 1921 took note of her reelection: “There previously had been grave doubts as to whether the office could be fulfilled successfully by a woman...the women and children with whom she came in contact find in her a friend ready to aid them and many of the kindness have been done by her outside of her official duties. She has ably proved that some features connected with the office can be looked after by a woman better than a man.” A proportion of funds raised by the town from taxes, licensing fees and fines were distributed to the overseers. Traditionally, destitute able-bodied residents were placed with families to do household chores or farm work in exchange for room and board. The families were expected to provide food, clothing and shelter, and medical care. Some professionals were paid by the town as records show that during the early 1800s Dr. Kissam received $35 a year to attend the poor. Children whose families could not maintain them or who were orphaned were placed as apprentices. The town also paid for younger children to be boarded with families. Widows were often placed with families as well, as an entry in the records of the Huntington Overseers of the Poor dated October 29 1736 states: “M. Wickes President of the Trustees-I desire you to Lett the Carrel here of Isaac brush have the Sum of Thirty four Shill it being the third payment for my keeping the widdow Jones in so doing you will Oblige your friend Benjamen Soper. Over time responsibility for the poor slowly evolved toward a more centralized model. By the mid-1800s with the growth in population, it was becoming obvious that the practice of placing the poor in homes was becoming unwieldly and inefficient. In 1821, It was determined that the poor should be placed in one location, and by 1824, the town purchased a farm on the the village green to house the poor. Those who refused to go would be denied any further aid. A manager was hired to work the farm with the residents. Proceeds from the farm went to support the house. Concurrently New York State passed a law requiring each county to construct a poorhouse. By 1871, a poorhouse was constructed in Yaphank and the town resolved to relocate the poor there, but Town overseers continued to provide for widows and families in their own homes. Eventually however care of the poor would be transferred from the local level to county and state. The last Overseer or Superintendent of the Poor was in 1929. In 1929, the year of the Great Depression, New York State enacted a repeal of the poor laws in order to expand responsibility for the poor from a local level to more centralized control with uniform standards throughout the state. Previous laws were deemed a hodgepodge of incoherent rules and amendments differing from town to town. Now each county would have a Superintendent of the Poor who had control over local overseers. The new state laws emphasized in home care and rehabilitation, with special concern for child welfare. The New Deal and the Social Security Act of 1935 solidified care for the poor and unemployed in Federal and State programs thus completing the transfer from town/local control to county, state and federal levels. For more detailed study see:

Bond, Elsie M. “New York’s Public Welfare Law”. Social Service Review, vol. 3, 1929, pp.412-21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30009380 Lindsay, Samuel McCune, “Social and Labor Legislation”. American Journal of Sociology, vol. 35, no.6. 1930 pp.967-81. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2766847 Huntington’s Legal History, Antonia S. Mattheou, Town Archivist, Town of Huntington Joanne Raia Archives. Companion publication to exhibition at the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Building, March 1-May 15, 2023. Stuhler, Linda S. “A Brief History of Government Charity in New York (1603-1900). VCU Libraries Social Welfare History Project. https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu Town of Huntington Records of the Overseers of the Poor Addendum 1729-1843. Rufus B. Langhans Huntington Town Historian, Town of Huntington 1992. |

AuthorThis blog has been written by various affiliates of the Huntington Historical Society. Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

Become a Member

Donate Today!

Signup For Our Newsletter

Thanks for signing up!

© Huntington Historical Society. All rights reserved.

The Huntington Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the Town of Huntington for its steadfast support.

The Huntington Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the Town of Huntington for its steadfast support.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed