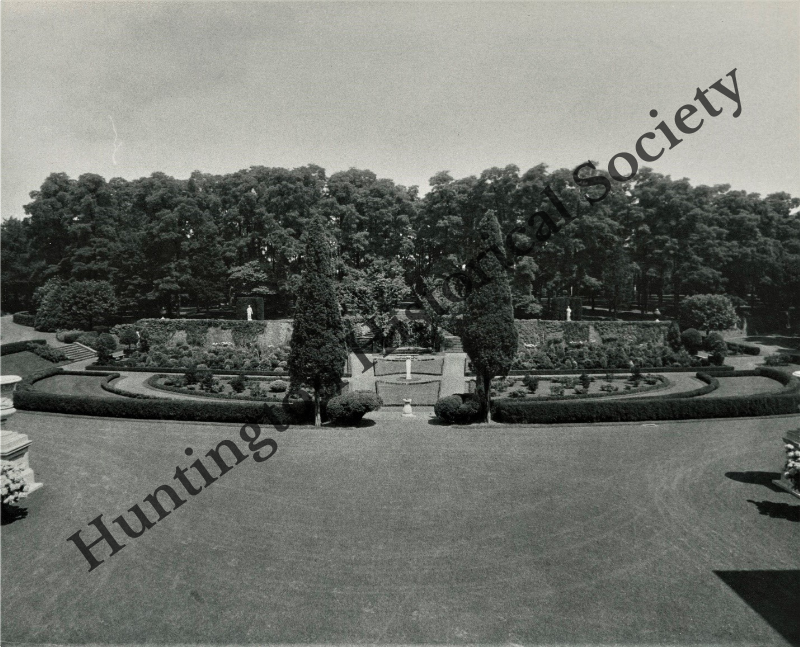

By Barbara LaMonicaAssistant Archivist The period from roughly 1877 to the early 20th century demarks the era known as the “Gilded Age.” The term Gilded Age was first coined by Mark Twain who, in his usual ironic fashion, used the word gilded to denote something that was shiny on the surface, but corrupt underneath. The Gilded Age coincided with a period of vast social and economic restructuring known as the Second Industrial Revolution. Urbanization and innovations in transportation, communication, production techniques and cheap immigrant labor opened up markets and allowed for the quick delivery of goods over vast distances. This growth in production created great wealth, but also great inequality and poverty, rendering the economic system inherently unstable, and culminating in the crash of 1929. The industrialists of this period - the railroad men, the oilmen, the steel men and the bankers -epitomized the lifestyle of the Gilded Age. Luxurious houses along Fifth Avenue were furnished with rich fabrics, marble, gold, carved ornate furniture imported from Europe and expensive antiques and art collections. Many mansions had ballrooms that hosted parties for hundreds of people. With an abundance of disposable wealth, families such as the Fricks, the Morgans, the Vanderbilts and the Coes built weekend or summer homes along the North Shore of Long Island, known as the Gold Coast. One such industrialist, Walter Jennings (1858-1933), built his estate in Lloyd Harbor. Jennings was the son of Standard Oil co-founder Oliver Burr Jennings, and was a first cousin to William, Percy and Geraldine Rockefeller. He was a director of Standard Oil New Jersey, president of the National Fuel Gas Company, director of the Bank of Manhattan, and trustee of the New York Trust Company, eventually to become Chase and Chemical Banks respectively. Beginning in 1895, Jennings began buying property in Cold Spring Harbor* (in buying 374 acres Jennings also acquired the Glenada Hotel, which he tore down). In 1898, he engaged architects Carrere & Hastings to design a Georgian mansion and the Olmstead Brothers to create the formal gardens. Carrere & Hastings had both apprenticed to Stanford White, and among their impressive achievements in Manhattan are the main branch of the New York Public Library on 5th Avenue, The Standard Oil Building, the Henry Clay Frick House and the Cunard Building. The Olmstead Brothers’ famous creations include Central Park, Bayard Cutting Arboretum, Forest Park and Prospect Park.

Jennings and his wife, Jean Brown Jennings, and their three children made Burrwood their summer residence. In retirement, Jennings moved permanently to Burrwood where he enthusiastically engaged in farming activities.

In a little over 50 years’ time, many of the Gold Coast Mansions were abandoned or torn down. The Great Depression, increased income taxes, rising land costs, high maintenance and personnel costs contributed to their demise as the cost of maintaining the estates became prohibitive. Some families lost their fortunes, or subsequent generations had less disposable income or simply found the style of the mansions not to their taste. Many estates were subdivided due to social and economic changes such as the movement to the suburbs of a growing middle class creating a demand for land to build single-family homes. Jennings died in 1933. His will stipulated that his wife could continue to live at Burrwood, while leaving the estate to his son. After Mrs. Jennings’ death, The Industrial Home for the Blind purchased the mansion and 32.5 acres for $90,000 in 1951. In 1952, it opened as a residence for the blind, but by the early 1980’s the maintenance and personnel costs became too expensive. Additionally, the resident population was decreasing due to more community support services enabling the disabled to remain in their homes or with family. After the remaining residents relocated to nursing homes or other housing programs, the property was sold in 1987 for 5.5 million to a New Rochelle developer who intended to restore the mansion to a single family home and subdivide the rest of the land to build 10 homes. However, the deal fell through and the mortgage holder seized the property. Another development company bought 10 lots and built houses. Unfortunately, there were no buyers willing to restore the house, and the Village of Lloyd Harbor had no landmark preservation ordinance in place that would have prevented destruction of the mansion. Burrwood was torn down in 1995. Property taxes at that time assessed at over $100,000 as well as 6.5 million dollars for restoration. If you still want to see a vestige of Burrwood’s opulence, you can take a stroll in the Elizabeth Street Garden in Manhattan’s Little Italy. Among various sculptures, you can sit under an Olmstead iron wrought gazebo from the Burrwood estate. *The property later became part of the Incorporated Village of Lloyd Harbor.

0 Comments

|

AuthorThis blog has been written by various affiliates of the Huntington Historical Society. Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

Become a Member

Donate Today!

Signup For Our Newsletter

Thanks for signing up!

© Huntington Historical Society. All rights reserved.

The Huntington Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the Town of Huntington for its steadfast support.

The Huntington Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the Town of Huntington for its steadfast support.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed