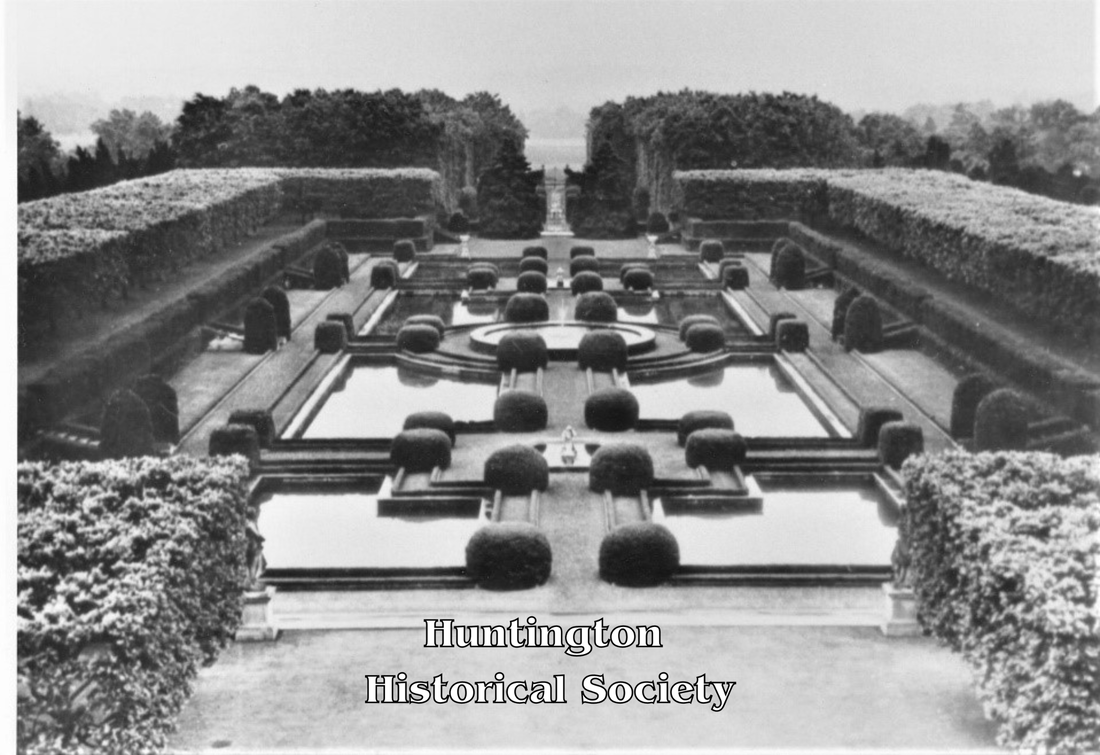

By Barbara LaMonica Assistant Archivist The George McKesson Brown Estate, aka Coindre Hall is an example of a Gold Coast mansion built around the turn of the century as a summer residence for wealthy entrepreneurs. Coindre Hall’s history is similar to that of other mansions of its time. Built during an era of great opulence, the estates eventually became untenable due to economic changes and increased taxation. Eventually the mansions and lands were sold off piece by piece by owners and descendants due to unaffordability and disinterest. Many were sold off to developers and torn down, others became public buildings or museums. Many languish as a tug of war between various community factions with differing agendas for their use. George McKesson Brown, heir to the McKesson Pharmaceutical Company fortune, purchased 135 waterfront acres facing Huntington Harbor. In approximately 1906 Brown commissioned architect Clarence Summer Luce to design a mansion inspired by chateaus he had seen while on vacation with his wife in the Loire Valley. The French Chateau style in architecture became popular in the United States around the late 19th century. This style reflected 16th century French chateaus with gabled roofs, conical towers, spires and arched entryways. Completed in 1912, the estate was known as West Neck Farm. It was essentially a self-contained manor with cows, chickens, pigs and bees as well as vegetable gardens. The out buildings, such as the garage and chauffeur’s quarters (now Unitarian Fellowship), the boat house, and the water tower were designed to reflect the style of the main mansion. At first a summer residence, West Neck Farm became a full time residence for the Browns by 1917. However, when Brown became financially strapped after losing much of his fortune after the 1929 stock market crash, he began selling off parcels of the estate’s land. In 1939 he moved into the farmhouse and sold the main house and 33 acres to the Brothers of the Sacred Heart who established a boarding school for boys. West Neck Farm was renamed Coindre Hall in honor of the founder of the religious order and the school remained open until 1971. In 1962 the former garage and chauffeur’s quarters, farmhouse and watertower was sold to the Unitarian Fellowship. In 1964 Brown died with no heirs and since then the fate of the estate has been debated.

In 1972 the Suffolk County Legislature voted to purchase the property for $750,000 with the intention of creating a harbor front park. The main mansion was leased to the Town of Huntington and continued to be used as a recreation and cultural center. In 1976 the county closed the park due to expensive upkeep. In 1981 the mansion was leased to Eagle Hill School, a school for students with learning disabilities, but by 1989 the school was struggling and had to close. Among proposals for the mansion were an expansion of Heckscher Museum, a repository for County records, a Gold Coast Museum. In 1980 the boathouse became the home of the Sagamore Rowing Club. During its tenure the rowing club put $73,000 to improve the safety of the boathouse but 70 percent of the building was eventually condemned forcing the rowing club to vacate. In 1985 the estate was listed on the National and New York State Register of Historic Places and in 1988 placed in the Suffolk County Historic Trust. It was given local landmark status by the Town of Huntington in 1990. In that same year Rep. Rick Lazio proposed the property be sold through a public referendum. In response to this the Alliance for the for the Preservation of Coindre Hall was founded with the goals of protecting, restoring and preserving the entire property. The Alliance fought off several attempt by the Legislature to sell the property. Today the mansion, which has undergone some restoration, now functions as a catering venue operated by Lessings. In 2020 the Suffolk County Legislature created an Advisory Board to oversee the rehabilitation of the property including the boathouse, the pier and the seawall. In 2023 the boathouse was put on the list of Endangered Places by Preservation Long Island. However, some residents are concerned that the park’s wetlands will be compromised by the planned renovations. The task ahead is to create a strategy that will include concerns for the natural environment as well as the preservation of an important historical legacy.

0 Comments

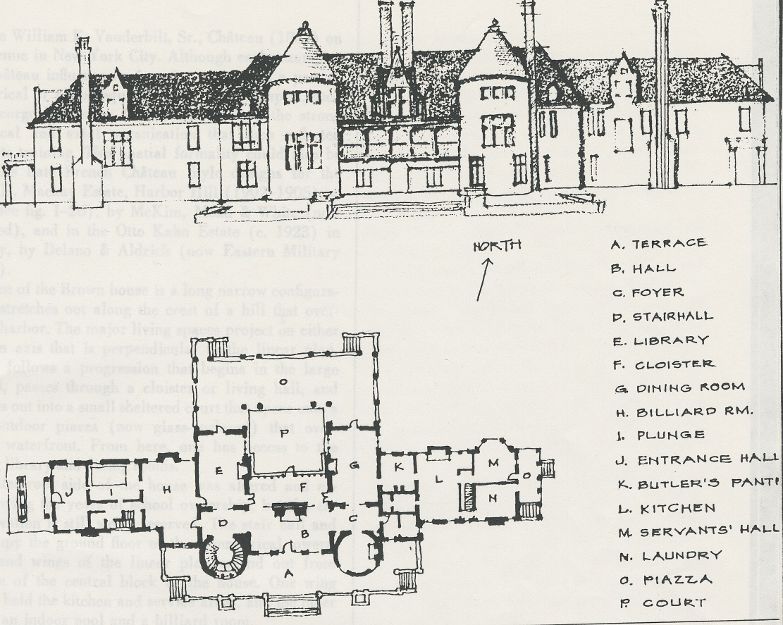

By Barbara LaMonica Assistant Archivist From Gilded Age castle, to sanitation union resort, to Merchant Marine training center, to military academy, and finally restored to its original grandeur as a luxury hotel, Oheka castle has a varied and controversial history. Completed in 1919, Oheka was built by investment banker and patron of the arts Otto Kahn. The chateau style mansion was intended as a summer home for his family while they were not in residence at their 80-room Italian Renaissance style mansion in New York City. Kahn’s previous country home, Cedar Court in Morristown, NJ was gifted to him and his wife Addie Wolfe by her father. However, after about 10 years the home burnt down, and Kahn, who had been denied membership in country clubs in Morristown because of his Jewish background, eventually decided to relocate. He bought 443 acres in Cold Spring Harbor where he intended to build a chateau style country home. Desiring to have an overview of the surrounding area, Kahn had a hill built before construction on the home began. It took two years to complete the man-made elevation which made the property the highest point on Long Island. Kahn engaged famed architects Delano and Aldrich to build the French chateau inspired home. Of utmost importance to him was that the home be fireproof, the result being that the Delano- Aldrich design in steel and concrete made it the first totally fireproof residential building.

Upon completion the 112,895 square foot castle had 127 rooms, 39 fireplaces, and employed 126 full time servants. It was the second largest home in the US, second to Vanderbilt’s Biltmore in Ashville, NC. Otto Kahn was born in Mannheim Germany in 1867. His father had eight children and had a career plan for each one. In spite of Otto’s desire to become a musician, his father placed him in a bank as a junior clerk. He eventually moved to London where he became second in command at Deutsche Bank. In 1893, he moved to the United States where he joined Kuhn, Loeb & Co. He became a partner with railroad builder E. H. Harriman in the task of restructuring the Union Pacific Railroad. Kahn gained a reputation as one of the most skillful reorganizers of railroads. He went on to restructure the Baltimore and Ohio, the Chicago and Eastern Illinois and other systems. In international finance, he negotiated for opening the Paris Bourse to American securities. A philanthropist and patron of the arts, Kahn was a stockholder and founding member of the Metropolitan Opera Company, and was a collector of paintings, tapestries, and sculptures. He authored several books on varied topics including art, history, and business. A few years after Kahn died in 1934 his wife Addie sold the castle for a mere $100,000 to the Welfare Fund of the Sanitation Workers of New York (Sanita). Oheka, renamed Sanita Lodge, was transformed into a country retreat for low paid department employees to vacation with their families. Addie, a patroness of the Women’s Trade Union League, stated she was pleased that the property could now be used to benefit so many. However, others in the area were not so pleased. The idea that “street sweepers” would use the luxurious surroundings triggered ethnic and class discriminations lurking beneath the surface. The Long Islander, a fierce opponent, ran an editorial on June 9, 1939 that read “…the finest land in Huntington is to be placed in the lowest category…the value of the parcels in the neighborhood will be correspondingly lowered.”

Because the lodge now consisted of a Horn and Hardart cafeteria, a cigar stand and a switchboard, Sanita should be considered a boarding house or hotel, not a strictly a residential building. Furthermore, the union did not get a Certificate of Occupancy. Because the union was a not-for-profit, local residents feared tax exemption would shift the tax burden onto them.

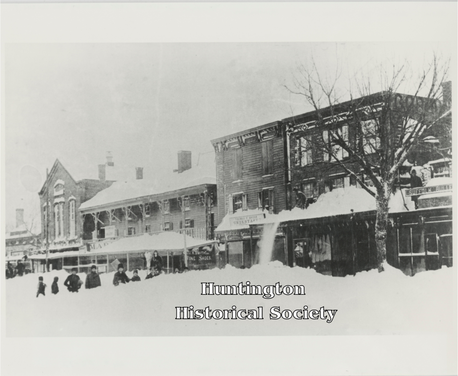

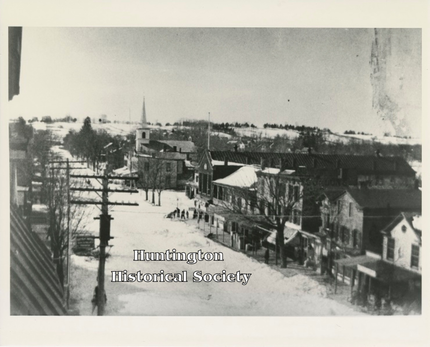

However, Sanita had many supporters among Huntington businessmen and residents. During a period of high unemployment and business depression, Sanita provided somewhat of a solution. The lodge hired local people as construction and service workers. Additionally, the lodge bought supplies from local businesses, and sanitation vacationers shopped in town. The Huntington Businessmen Association started a petition in favor of keeping Sanita open. The first petition had over 1400 signatures. By this time Mayor LaGuardia got involved and offered to act as a mediator. He set up a meeting between the town board and Sanita. He proposed that the Sanitation Union would be willing to pay partial taxes on the property. But the board held firm. It refused a certificate of occupancy and refused tax exemption. “I would not want to be as dead as this proposal” claimed LaGuardia. In the meantime, the union said it would no longer pursue legal means. “We do not want to be somewhere where we are not wanted,” Sanitation Director Carey stated. As of April 1940 the Sanita cause was defeated. Eventually the Sanitation Union, with the support of Franklin Roosevelt, did find suitable property upstate. The property reverted to the Kahn family and almost immediately was subdivided and bought by a local developer. The town approved rezoning to 1/3-1/4 acre plots for the construction of homes. In 1942 the Merchant Marine requisitioned the abandoned mansion and Oheka became a radio operator school through 1945. In 1948 Eastern Military Academy purchased it and ran a boarding school until 1979. For the next four years Oheka fell into ruin. In 1984 developer Gary Melius purchased the home and began restoration. Today, restored to its Gilded Age opulence, Oheka Castle is a luxury hotel and event venue. By Barbara LaMonica Assistant Archivist Notwithstanding the occasional snowstorm, winters have been getting warmer and wetter. In the past winters had more frequent single digit temperatures and several snowstorms a season. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported for the 2022-2023 season the average temperature was 2.7 degrees above average, and the precipitation average made it the third wettest winter on record. The east coast had one of the least snowy seasons, but plenty of rain. In addition to the famous March snowstorm of 1888, the Great Christmas Blizzard of 1947, the blizzards of Feb 2006, and January 2016 a sampling of Huntington’s previous winters as recorded in the Long Islander illustrates the contrast between past and present weather. Although greatly inconvenienced by the storms the populace often took joy in the fact that the conditions afforded great sleigh riding. Main Street in Huntington after the blizzard of 1888 1839- It snowed for three days rendering all roads impassable, but “We now have fine sleighing and our citizens both old and young are proving by actual demonstration the country sleigh rides in winter are nothing to sneeze at!” (Long Islander 12/27/1839.) 1853-A large snowstorm completely stopped the Long Island Railroad for five days. However “The beautiful sleighing has been well improved by our citizens...the streets are filled with fine teams, handsome sleds filled with gay flowing robes and jingle bells. A party of eighteen sleds from this village and Cold Spring Harbor made a visit to Hempstead on Tuesday.” (Long Islander 1/21/1853) 1865-Extremely cold weather, temperature hovers around zero with very little variation since December. The sound was frozen over “...as far as can be seen from the necks.” Long Islander 2/17/1865 1866-temperatures ranging from ten to thirteen below zero for consecutive days, and fourteen and fifteen below in New York City and Brooklyn. “...almost everyone was willing to admit that it was cold, and if they were not, their frozen ears and noses attested to it.” (Long Islander 1/12/1866) 1896-The long Islander reported an unusual snowstorm in May. Due to the raging snowstorm, a schooner was driven onto Little Reef to the east of the Eaton’s Neck Lighthouse. “The waters of the sound were lashed into a fury by the gale and four of the five men on the vessel, fearing she would go to pieces, launched the yawl boat...the boat was swamped and two of the men drowned. The fall of snow was followed by a storm of sleet afforded an unexpected opportunity for sleigh riding.” 1936- Long Islander reported that Huntington Harbor was completely covered in ice from shore to shore, the thickness approaching 16 inches. (Long Islander 2/21/1936. In light of the recent earthquake in Queens and on Roosevelt Island, a slight digression. In August 1884, an earthquake hit Long Island. According to the Long Islander, the shock was felt in Washington D.C., Canada, Ohio and the Atlantic Coast. “Crockery and glassware were shaken on tables...doorbells in several houses in our village rang violently...Some clocks were stopped... and chairs were moved with persons in them...one lady Mrs. Pettit eighty –two years of age was rolled from here bed. Several persons fainted and sick people were very much affected. ...the death of Mrs. Almed Tillot was very much hastened by the shock as she was suffering from a nervous affliction...others were greatly affected in their heads.” (Long Islander 8/15.1884) Main Street in Huntington covered with snow, year unknown

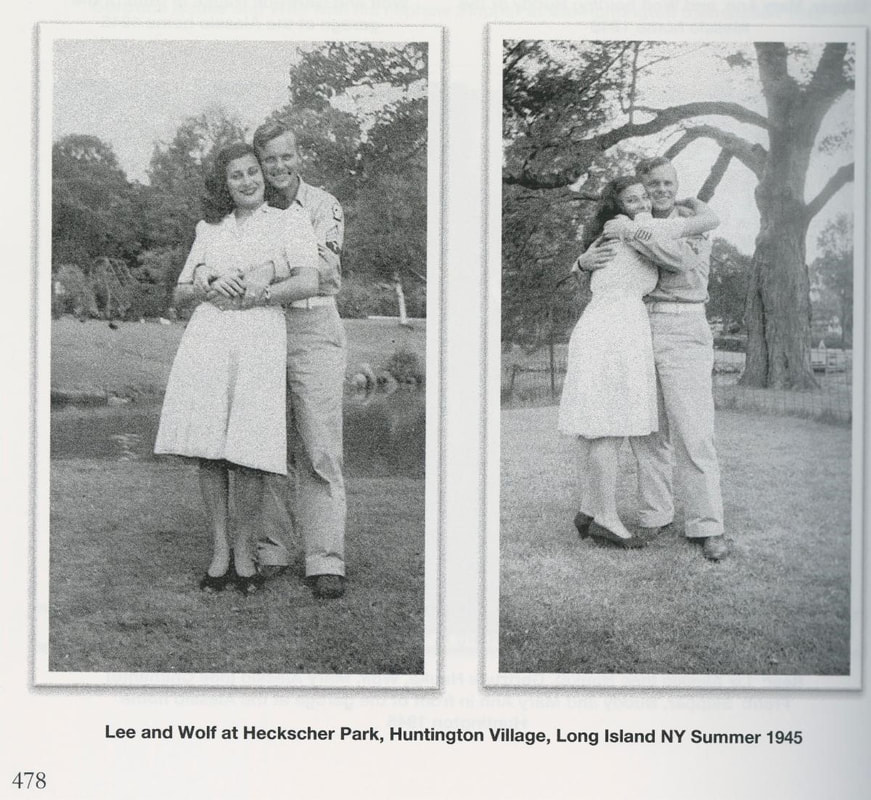

By Barbara LaMonica Assistant Archivist  Commack Cemetery If you are fascinated by cemeteries and love to spend time reading tombstone inscriptions, looking for the graves of famous people, or simply enjoying the verdant and peaceful surroundings of park-like burial grounds then you qualify as a true taphophillac (Taphophilla -ancient Greek taphos, funeral rites, burial, philia, love). Genealogists, historians, and photographers are drawn to cemeteries for various reasons. Both professional and amateur historians go to cemeteries for the information they can reveal about a town’s history. For example, family names which coincide with names of local streets indicate those families were prominent in the community. In the earliest burial sites, which were often in churchyards, the areas closest to the church, or those facing east were reserved for the more important citizens. Death rates and infant mortality can be measured. Large groupings of death dates can indicate an epidemic or other natural catastrophe. Genealogists can find previously unknown ancestors as family members were often buried next to each other or in mausoleums. Birth and death dates can be compared to written records. Because the census comes out only every ten years, tombstones may be the only record for a child who was born and died within that period. Many cemeteries have ornate sculptures and elaborate mausoleums considered artistic architecture, which attracts photographers. Older weathered tombstones have interesting textures and contrast creating pleasing images. Park like cemeteries provide lush landscapes as well as being habitats for wildlife. Burial grounds and grave markers have changed over the years. In early colonial America, burial grounds were mainly in churchyards or in the center of a village, preferably on a hill. In keeping with strict puritan tradition, grave markers were plain usually made of fieldstone or wooden planks, with only the name and date of death. Eventually sandstone and slate were used, etched with simple verse or something about the person’s life. Images of crossbones and skulls were prevalent as reminders of mortality. Later on, more positive images of winged cherubs emphasizing the afterlife became popular. As churchyards became overcrowded and real estate values rose, rural cemeteries were established on the outskirts of towns and cities. Not being associated with a particular church, many of these were public and non-denominational. This led to more landscaped cemeteries that were garden- like. With winding paths, benches, and shade trees, cemeteries were now conducive for family outings and even picnicking. Founded in 1831 Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts was the first rural cemetery in American. Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn followed shortly after in 1838. There are many historic cemeteries within the Town of Huntington for one to explore. Four in particular are within the the village area. The Old Burial Ground- Located at 228 Main Street, the Old Burial Ground was founded in the 17th century and in 1981 was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. It is the former location of an English revolutionary fort. After the American Revolution, the fort was dismantled and the burial grounds restored. There one can find graves of Revolutionary and Civil War veterans. By Barbara LaMonica Assistant Archivist When former Huntington resident Daniel Thomas Nauke discovered boxes of forgotten letters written between his parents during WWII, he brought the letters home and put them on a shelf. It took the COVID lockdown years later to prompt Daniel to finally read and organize the letters. He found they revealed not only a love story between his parents but also a story of immigrant families, a neighborhood, and life during WWII.

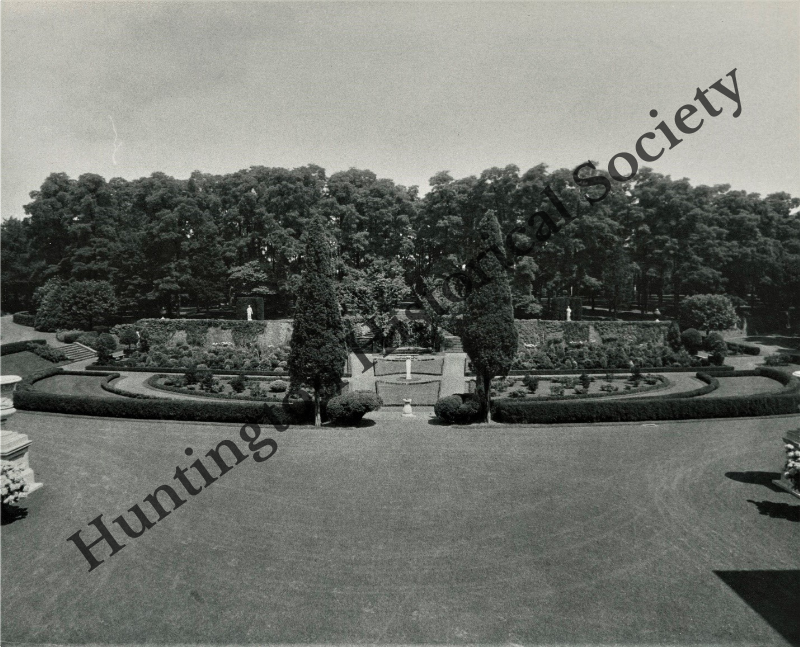

Using the letters as a springboard, Daniel began a research project involving old maps, censuses, and newspaper articles to recreate the time frame of the neighborhood and the families that lived there. The project evolved into the book Always Faithful Letters Between An American Soldier and His Hometown Sweetheart During WWII. The result of this research is a work that is not only a personal love story, but also an historical document of the times in Huntington Station. By the 1920s, the streets in Huntington Station had been laid out, building lots were being sold and homes built. Immigrants came to this area and eventually settled in the new community, creating a diverse neighborhood of Germans, Irish, Italian, and Polish families to name a few. This is where the author’s parents, Lee Alessio and Wolfgang Nauke, grew up across the street from each other on East 4th Street and Fairground Avenue. Lee was the daughter of Salvatore Alessio from Acri Italy, and Wolfgang immigrated with his parents from Dresden, Germany in 1923. Interspersed with the letters, the author provides photographs, maps, postcards, and WWII memorabilia, as well as an extensive index of families and businesses that populated the area. This book illustrates that old family documents can be more than personal memories, they can provide historical insight of interest to everyone. If you are interested in purchasing this book when it becomes available, please contact [email protected]. By Barbara LaMonicaAssistant Archivist The period from roughly 1877 to the early 20th century demarks the era known as the “Gilded Age.” The term Gilded Age was first coined by Mark Twain who, in his usual ironic fashion, used the word gilded to denote something that was shiny on the surface, but corrupt underneath. The Gilded Age coincided with a period of vast social and economic restructuring known as the Second Industrial Revolution. Urbanization and innovations in transportation, communication, production techniques and cheap immigrant labor opened up markets and allowed for the quick delivery of goods over vast distances. This growth in production created great wealth, but also great inequality and poverty, rendering the economic system inherently unstable, and culminating in the crash of 1929. The industrialists of this period - the railroad men, the oilmen, the steel men and the bankers -epitomized the lifestyle of the Gilded Age. Luxurious houses along Fifth Avenue were furnished with rich fabrics, marble, gold, carved ornate furniture imported from Europe and expensive antiques and art collections. Many mansions had ballrooms that hosted parties for hundreds of people. With an abundance of disposable wealth, families such as the Fricks, the Morgans, the Vanderbilts and the Coes built weekend or summer homes along the North Shore of Long Island, known as the Gold Coast. One such industrialist, Walter Jennings (1858-1933), built his estate in Lloyd Harbor. Jennings was the son of Standard Oil co-founder Oliver Burr Jennings, and was a first cousin to William, Percy and Geraldine Rockefeller. He was a director of Standard Oil New Jersey, president of the National Fuel Gas Company, director of the Bank of Manhattan, and trustee of the New York Trust Company, eventually to become Chase and Chemical Banks respectively. Beginning in 1895, Jennings began buying property in Cold Spring Harbor* (in buying 374 acres Jennings also acquired the Glenada Hotel, which he tore down). In 1898, he engaged architects Carrere & Hastings to design a Georgian mansion and the Olmstead Brothers to create the formal gardens. Carrere & Hastings had both apprenticed to Stanford White, and among their impressive achievements in Manhattan are the main branch of the New York Public Library on 5th Avenue, The Standard Oil Building, the Henry Clay Frick House and the Cunard Building. The Olmstead Brothers’ famous creations include Central Park, Bayard Cutting Arboretum, Forest Park and Prospect Park.

Jennings and his wife, Jean Brown Jennings, and their three children made Burrwood their summer residence. In retirement, Jennings moved permanently to Burrwood where he enthusiastically engaged in farming activities.

In a little over 50 years’ time, many of the Gold Coast Mansions were abandoned or torn down. The Great Depression, increased income taxes, rising land costs, high maintenance and personnel costs contributed to their demise as the cost of maintaining the estates became prohibitive. Some families lost their fortunes, or subsequent generations had less disposable income or simply found the style of the mansions not to their taste. Many estates were subdivided due to social and economic changes such as the movement to the suburbs of a growing middle class creating a demand for land to build single-family homes. Jennings died in 1933. His will stipulated that his wife could continue to live at Burrwood, while leaving the estate to his son. After Mrs. Jennings’ death, The Industrial Home for the Blind purchased the mansion and 32.5 acres for $90,000 in 1951. In 1952, it opened as a residence for the blind, but by the early 1980’s the maintenance and personnel costs became too expensive. Additionally, the resident population was decreasing due to more community support services enabling the disabled to remain in their homes or with family. After the remaining residents relocated to nursing homes or other housing programs, the property was sold in 1987 for 5.5 million to a New Rochelle developer who intended to restore the mansion to a single family home and subdivide the rest of the land to build 10 homes. However, the deal fell through and the mortgage holder seized the property. Another development company bought 10 lots and built houses. Unfortunately, there were no buyers willing to restore the house, and the Village of Lloyd Harbor had no landmark preservation ordinance in place that would have prevented destruction of the mansion. Burrwood was torn down in 1995. Property taxes at that time assessed at over $100,000 as well as 6.5 million dollars for restoration. If you still want to see a vestige of Burrwood’s opulence, you can take a stroll in the Elizabeth Street Garden in Manhattan’s Little Italy. Among various sculptures, you can sit under an Olmstead iron wrought gazebo from the Burrwood estate. *The property later became part of the Incorporated Village of Lloyd Harbor. By Barbara LaMonicaAssistant Archivist The Huntington Historical Society received a $39,000 grant from the New York State Program for the Conservation and Preservation of Library Research Materials Discretionary Grant Program to conserve and digitize 160 audio cassettes and 16 reel-to-reel tapes comprising the Society’s oral history collection. The goal of the audio preservation is to produce an accurate and intelligible reproduction of the source material and create accessible Mp3 files. The collection was sent to the Northeast Document Conservation Center in Massachusetts where a total of 244 hours of recordings were transferred, processed, and repaired. The interviews span the years from the 1950s to the 1980s, and depict through first person accounts, the transformation of Huntington from an early 20th century rural community through the urban renewal efforts of the 1960s-1970s. Included in this collection is a special project developed in conjunction with the Town of Huntington entitled “Reaching for a Dream.” The project documents the history and contributions of Huntington’s local ethnic communities. Sixty-five persons from the African-American, Italian, and Latino communities were interviewed between 1987 and 1988. The preservation of these oral history interviews insures that a significant part of Huntington’s history, told from the standpoint of local townspeople, will now be accessible to the public. Reaching for a Dream Oral History

By Barbara LaMonicaAssistant Archivist

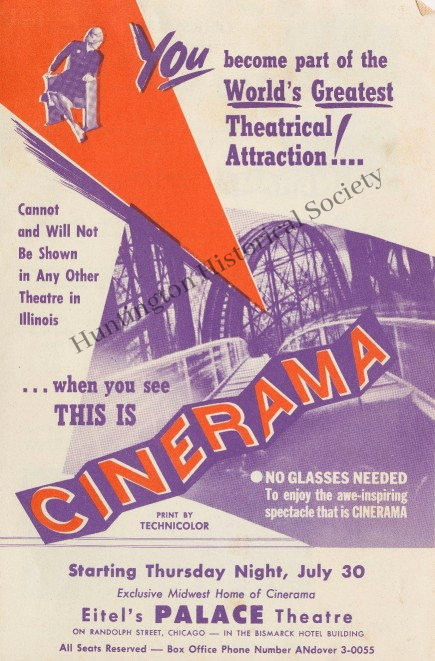

He returned to Paramount in 1929 and left in 1936 to begin work on special features for the New York World’s Fair. He created special motion pictures projected on the interior of the Perisphere, an enormous modernistic structure that served as the central theme of the fair. He built his first model for the Cinerama process but it was considered too expensive and radical at the time. During this period, he bought the Kenyon Instrument Company of Boston and relocated it to Huntington as the Kenyon Instrument Company. The new company produced nautical and aircraft instruments. During WWII, he developed the Waller Gunnery Trainer, a simulator utilizing multiple cameras projecting pictures of moving planes onto a conclave screen. This resulted in producing realistic aerial battle situations, thus showing gunners how to hit them. The U.S. Air Force, Navy and the British Admiralty used the trainer, which is credited with saving over 350,000 lives during combat.

Essentially the process Waller created called for three 35 mm cameras equipped with 27mm lenses. Each camera photographed one-third of the picture in a crisscross pattern. The film was projected from three projection booths onto a large curved screen. The process attracted Lowell Thomas who organized a corporation to further market Cinerama. Louis B. Mayer was Chairman, Thomas was Vice President and Waller was Chairman of the Board.

On September 30, 1952, This is Cinerama opened in New York City to a capacity crowd. The film opened with a breathtaking rollercoaster ride, and critics lauded the production, seeing it as an alternative to the rising popularity of television. The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm and How the West Was Won were two of the first features to be shot in Cinerama. However, it soon became obvious that the Cinerama process was too cumbersome to shoot with three cameras mounted on one crane, and the need for three projection booths with at least three projectionists added to a prohibitive cost. Most existing movie theatres could not be easily converted to accommodate the process, as the cost for this could be as high as $75,000. Eventually producers decided to shoot on 70mm film with a single camera and project onto a larger screen with a single projector. Even though the Cinerama process gradually faded out it still remains a significant contribution to cinema technology being a precursor to IMAX and Virtual Reality. By Barbara LaMonicaAssistant Archivist

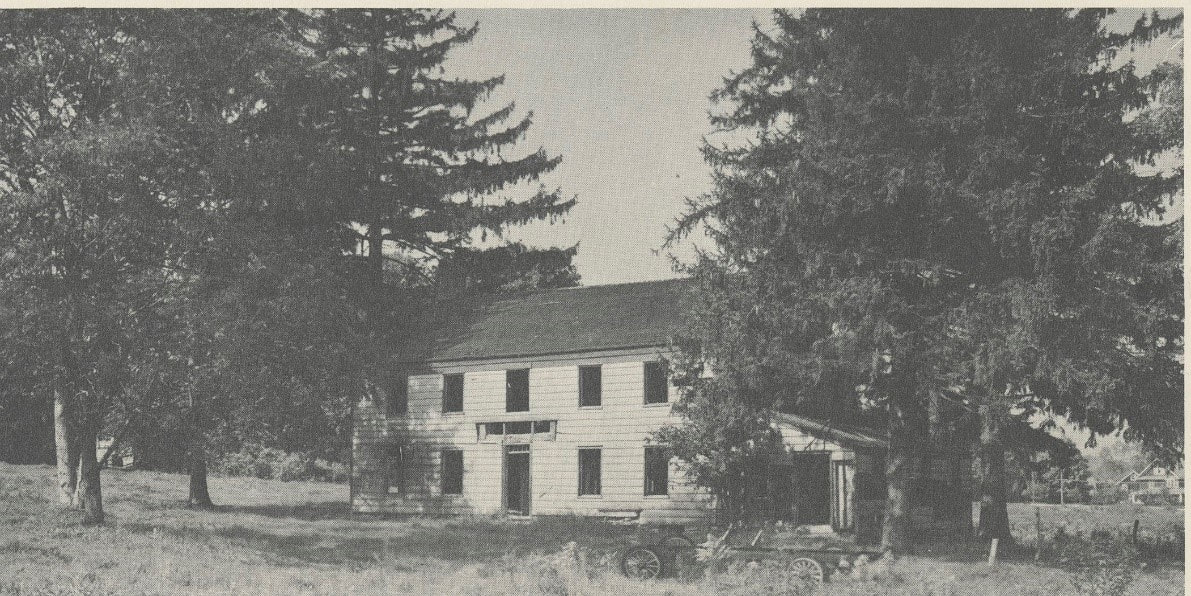

This law addressed the gap in care of the poor created by Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries, as the monasteries had been the main source of charity. The Elizabethan law established the precept of local control, meaning each village had the responsibility for its own poor. Local officials had the power to raise taxes and appoint an overseer to administer the charity funds. A later law, The Law of Settlement and Removal, empowered villages to expel persons back to their home village should they become dependent, insuring that “no vagabonds or beggars allowed. “ As early as 1687, the Province of New York passed a law mandating towns and counties take care of their own poor. Pre and post revolution New York continued to establish statutes such as binding out poor children as apprentices and servants, and the establishment of poor or work houses. Eventually children were removed from these institutions and placed in orphanages. According to Huntington Town Records, the town trustees who acted as overseers evaluated destitute residents on a case-to-case basis. Eventually separate overseers were appointed. These individuals came from prominent Huntington families. Town overseer records show in 1763 the first overseers came from the Brush, Platt, and Wood families. Over the years such personages as William Woodhull, Solomon Ketchum, John Rogers, Israel Scudder, Hiram Baylis served multiple terms. As an interesting aside, it was not until 1921 that the first woman overseer, Maude E. Henschell, was elected. A Brooklyn Times Union article dated December 29, 1921 took note of her reelection: “There previously had been grave doubts as to whether the office could be fulfilled successfully by a woman...the women and children with whom she came in contact find in her a friend ready to aid them and many of the kindness have been done by her outside of her official duties. She has ably proved that some features connected with the office can be looked after by a woman better than a man.” A proportion of funds raised by the town from taxes, licensing fees and fines were distributed to the overseers. Traditionally, destitute able-bodied residents were placed with families to do household chores or farm work in exchange for room and board. The families were expected to provide food, clothing and shelter, and medical care. Some professionals were paid by the town as records show that during the early 1800s Dr. Kissam received $35 a year to attend the poor. Children whose families could not maintain them or who were orphaned were placed as apprentices. The town also paid for younger children to be boarded with families. Widows were often placed with families as well, as an entry in the records of the Huntington Overseers of the Poor dated October 29 1736 states: “M. Wickes President of the Trustees-I desire you to Lett the Carrel here of Isaac brush have the Sum of Thirty four Shill it being the third payment for my keeping the widdow Jones in so doing you will Oblige your friend Benjamen Soper. Over time responsibility for the poor slowly evolved toward a more centralized model. By the mid-1800s with the growth in population, it was becoming obvious that the practice of placing the poor in homes was becoming unwieldly and inefficient. In 1821, It was determined that the poor should be placed in one location, and by 1824, the town purchased a farm on the the village green to house the poor. Those who refused to go would be denied any further aid. A manager was hired to work the farm with the residents. Proceeds from the farm went to support the house. Concurrently New York State passed a law requiring each county to construct a poorhouse. By 1871, a poorhouse was constructed in Yaphank and the town resolved to relocate the poor there, but Town overseers continued to provide for widows and families in their own homes. Eventually however care of the poor would be transferred from the local level to county and state. The last Overseer or Superintendent of the Poor was in 1929. In 1929, the year of the Great Depression, New York State enacted a repeal of the poor laws in order to expand responsibility for the poor from a local level to more centralized control with uniform standards throughout the state. Previous laws were deemed a hodgepodge of incoherent rules and amendments differing from town to town. Now each county would have a Superintendent of the Poor who had control over local overseers. The new state laws emphasized in home care and rehabilitation, with special concern for child welfare. The New Deal and the Social Security Act of 1935 solidified care for the poor and unemployed in Federal and State programs thus completing the transfer from town/local control to county, state and federal levels. For more detailed study see:

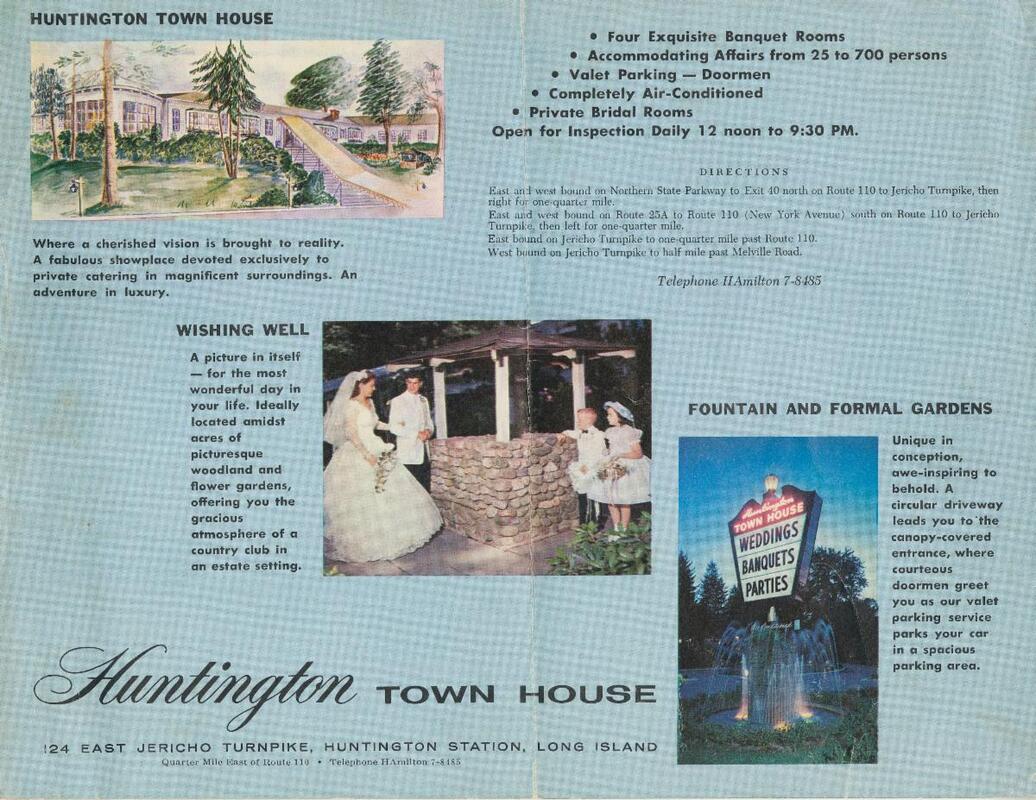

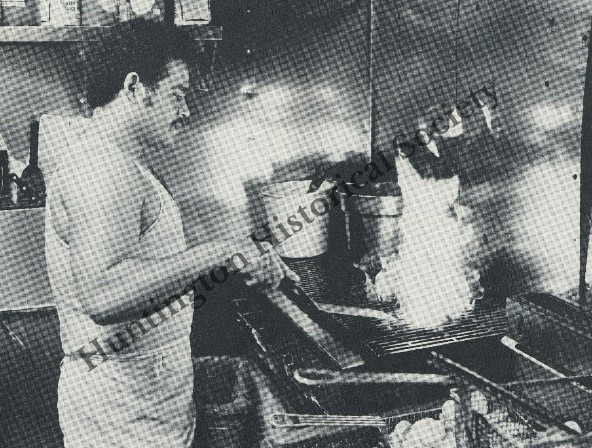

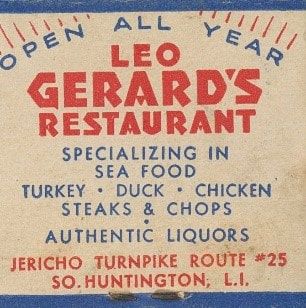

Bond, Elsie M. “New York’s Public Welfare Law”. Social Service Review, vol. 3, 1929, pp.412-21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30009380 Lindsay, Samuel McCune, “Social and Labor Legislation”. American Journal of Sociology, vol. 35, no.6. 1930 pp.967-81. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2766847 Huntington’s Legal History, Antonia S. Mattheou, Town Archivist, Town of Huntington Joanne Raia Archives. Companion publication to exhibition at the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Building, March 1-May 15, 2023. Stuhler, Linda S. “A Brief History of Government Charity in New York (1603-1900). VCU Libraries Social Welfare History Project. https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu Town of Huntington Records of the Overseers of the Poor Addendum 1729-1843. Rufus B. Langhans Huntington Town Historian, Town of Huntington 1992. By Barbara LaMonicaAssistant Archivist  For nearly 50 years, the Huntington Town House reigned as a celebrated venue for weddings, proms, bar mitzvahs, and anniversary parties. Politicians and celebrities such as the Beach Boys, Steve Levy, Hillary Clinton, and Donald Trump held events there. More importantly, the Town House engenders memories for the thousands of people whose milestone celebrations were held under its crystal chandeliers. The evolution of the Town House begins in the late nineteenth century with a restaurateur and hotelier family, the Gerards. William Gerard operated hotels in Cold Spring Harbor-the Laurelton on the west side of the harbor, and after he sold the Laurelton in 1880, he acquired the Glenda, Matchbook Covers for Gerard's a castle built in 1853 on the east side of the harbor. His son Leo, born in 1892, grew up in the hotels, and eventually followed in his father’s footsteps. Initially Leo became manager at the Huntington Yacht Club in 1927, and then in 1932 he opened Gerard’s Restaurant on 25A in Cold Spring Harbor (later to become The Moorings Restaurant). Gerard’s Restaurant became so popular that even after expanding the building he still had to turn customers away. This prompted him to look for other locations to accommodate larger crowds. In March 1937, Leo purchased the 5-acre Bruns estate on the south side of Jericho Turnpike ½ mile east of Route 110. The estate home had a large dining room that could seat over 100 people in addition to several bedrooms. Leo Gerard added a dance floor, a taproom, and a cocktail lounge.  In 1957, Gerard, ready to retire after a solidly successful run, sold the property to Thomas Manno, who in anticipation of the coming baby boom generation, turned it into a strictly catering business and christened it the Huntington Town House. Manno expanded banquet facilities to 11 rooms. Multiple kitchens equipped with machines could turn out 5,000 meatballs in one hour, and high-pressure mashed potato hoses could gush out 2,000 potato rosettes in a comparable amount of time. The property comprised 20 acres with parking spaces for 2,000 cars. Now renown as the only catering facility of its kind, the Town House attracted customers from all over the Island as well as Queens, Manhattan, the Bronx, and Westchester. Manno had plans to build a conference center with lodgings on the property, but after he passed away, his widow sold the Town House to Rhona Silver in 1997 for 7.6 million dollars. Silver was the most flamboyant and successful Town House owner. She reached icon status as the “queen of catering” presiding over a business that in addition to weddings, night after night hosted charity dinners and corporate events. It was even the site of a concert by the rapper 50 Cent. She specialized in creating spectacle and fantasy, a bride and groom arriving in the grand ballroom in a coach drawn by two white horses, or a couple landing on the lawn in a hot air balloon. She was in demand for offsite catering as well, such as catering an affair for the prime minister of Israel and being the only caterer allowed inside Mar-a-Lago. As a child, she grew up in her family’s catering business in the Bronx, and later opened a catering business in space she rented in Temple Beth El in Cedarhurst where she was known as the only Glatt Kosher caterer. Silver had plans to construct a lodging and conference center at the Town House which had preliminary approval when Manno had first proposed the idea. However, these plans never came to fruition as Silver sold the Town House to Lowes for $38.5 million in 2007. She suddenly found herself mired in several lawsuits. The real estate company sued her for commissions and her half-brother sued her claiming he owed half the Town House business. Silver then initiated her own lawsuit suing her boyfriend, Barry Newman, real estate developer, for $25.9 million claiming he forged her name on documents for the sale and ripped her off for millions leaving her destitute. Newman claims he loaned her millions over the years for the business but it really supported her lavish lifestyle. He claims the proceeds from the sale were used to pay off debtors. Who knows what really happened? Unfortunately, Silver died of a heart attack in 2017, with the law suits still unresolved. The Huntington Town House, a repository of memories for a generation, was ultimately demolished in 2011 to be replaced by Target. |

AuthorThis blog has been written by various affiliates of the Huntington Historical Society. Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

Become a Member

Donate Today!

Signup For Our Newsletter

Thanks for signing up!

© Huntington Historical Society. All rights reserved.

The Huntington Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the Town of Huntington for its steadfast support.

The Huntington Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the Town of Huntington for its steadfast support.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed