By Toby Kissam

The surviving 1825 "Eagle" that stood above the "sails" on the Daniel Sammis Saw Mill. The year is 1826:

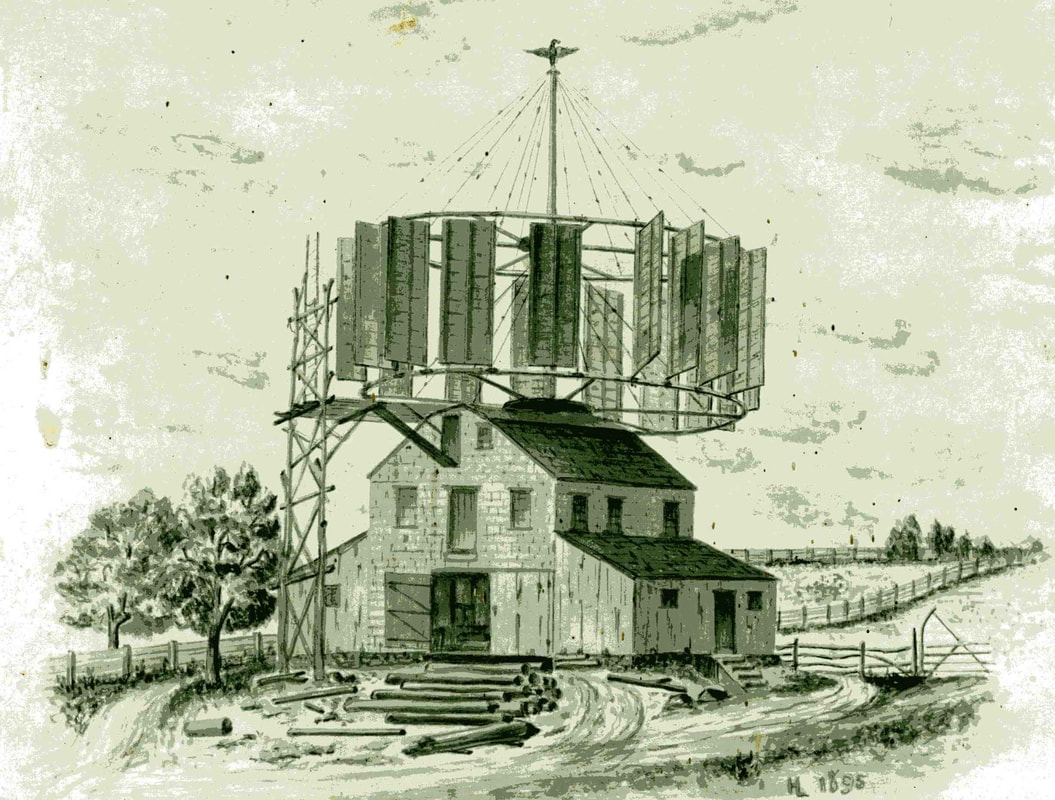

Daniel Sammis (1787-1869), a 5th generation Sammis in Huntington, erected a large and unusual saw mill, powered by wind, in 1825. It was described as “The most conspicuous building in the place.” One of his clients was Carman Smith. A circular dated December 21, 1826, and issued by the proprietor, stated the purpose for which the mill was built. Sammis designed and built this unique mill, possibly from earlier Dutch examples in New Amsterdam. Built on the ridge, north of Main Street, between West Neck Road and Wall Street, in 1846 the mill was moved closer to Main Street into what is today a municipal parking lot across from the Post Office. In 1867, a hurricane blew off the circular carousel structure that powered the mill and its wind directional, breaking one of the eagle’s wings. The building was used after as a barn until it was torn down in the early 20th century. Henry Lockwood (1838-1901), a grandson of Daniel Sammis, whose family owned the marble foundry next door and whose mother was the daughter of Daniel Sammis, recalled when he and his friends, as young boys, would climb the circular structure and “ride the wind.” Although considered dangerous, reportedly no one was seriously injured. Late in his life, Henry drew the sketch of the mill for an article in the Brooklyn Eagle. In 1923, the Lockwood House was torn down and the “Eagle,” although damaged during the 1867 hurricane, was donated to the Huntington Historical Society and is today the symbol for the Society. You can visit this almost 200-year-old artifact at the History and Decorative Arts Museum in the Soldiers & Sailors Memorial Building on Main Street. The 1895 sketch of the saw mill done by the grandson of Daniel Sammis, Henry Lockwood, for the article in the Brooklyn Eagle.

0 Comments

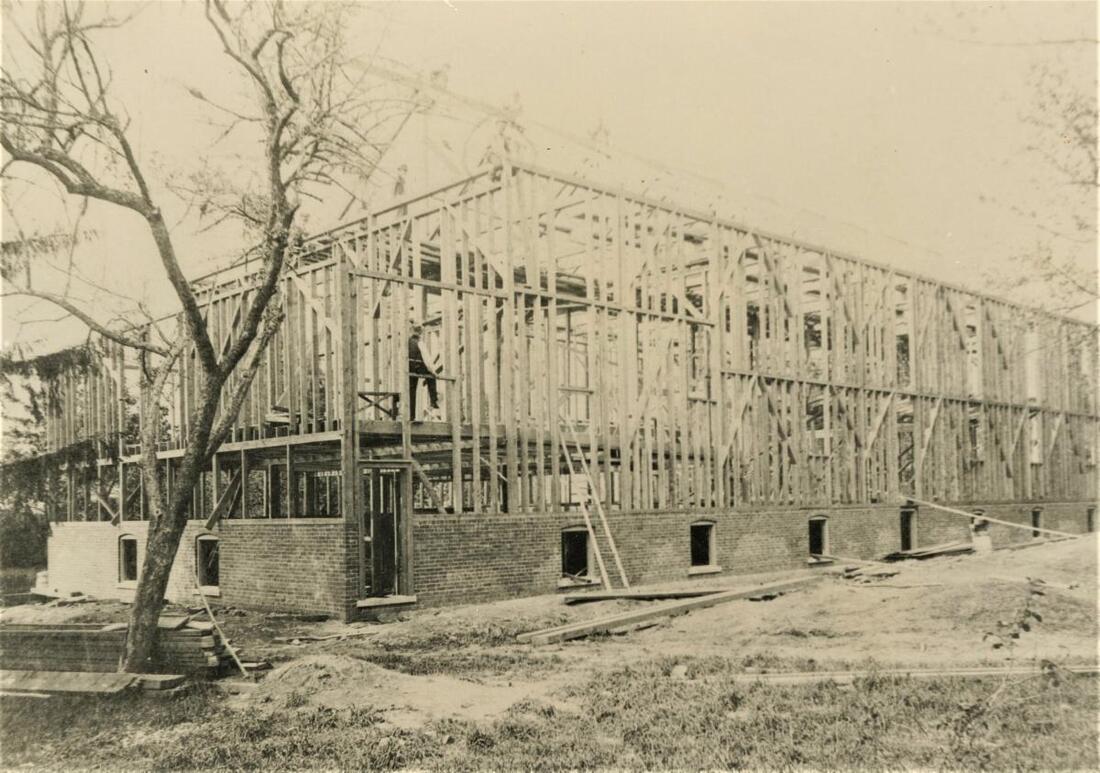

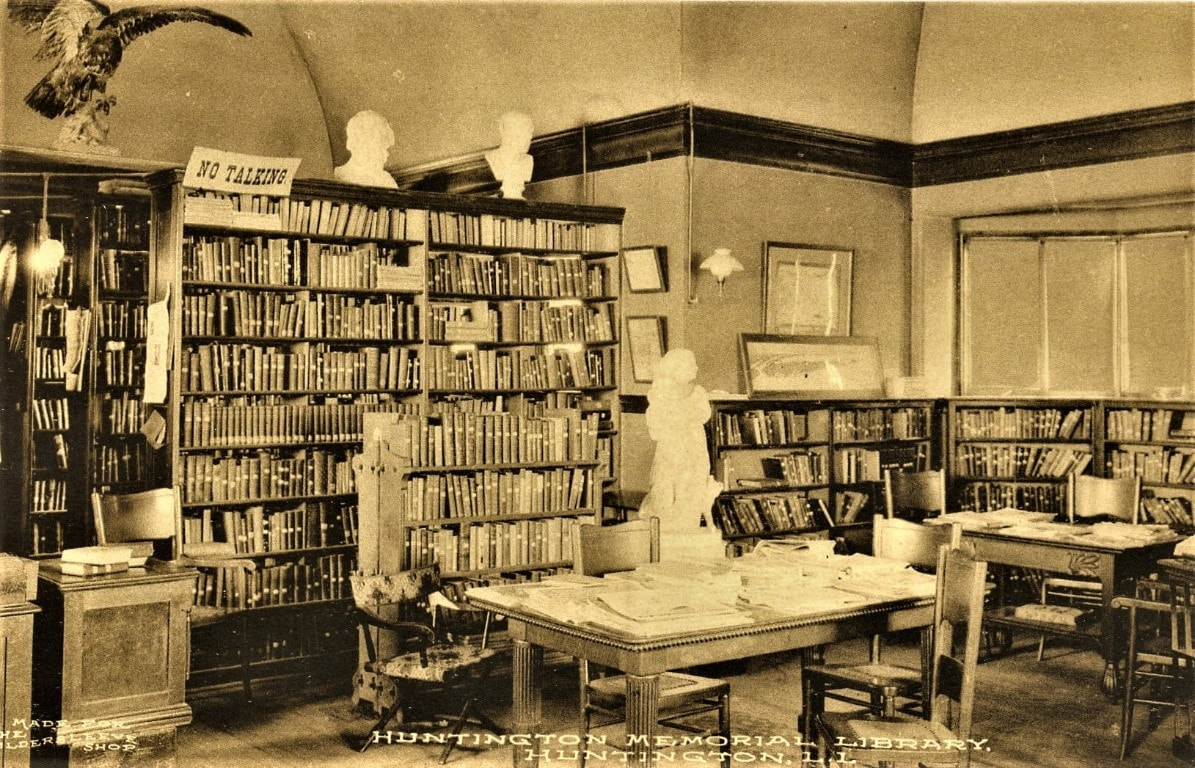

by Barbara LaMonicaAssistant Archivist Built for $9,000 in 1892 by a consortium of local businessmen, the Huntington Opera House was a nexus for local as well as outside talent, distinguished lecturers, concerts, high school graduations, poultry and horticulture shows and political rallies. However nary an opera was performed there. In the 19th century, theaters were often called opera houses because opera was seen as carrying a hint of cultural sophistication, while theater was still considered somewhat disreputable. In 1910, the Opera House burned to the ground. The fire, discovered around midnight is believed to have started in a cloakroom. The wooden structure burned with such ferocity that it was considered a miracle the rest of the block, consisting of various stores, was not also consumed. This was thanks to the efforts of the Huntington, Halesite, Fairground, Cold Spring Harbor, and Centerport fire departments. The firefighters laid half a dozen lines of hose to wet down the adjoining buildings, thus keeping the fire contained. Some buildings were saved by a fortuitous northwest wind that carried the sparks far above and away from the street. A March 18, 1910 editorial in the Long Islander advocates strongly for a new opera house as “Such a large, rapidly growing and prosperous village as Huntington cannot do long without an Opera house.” The editorial continues with recommendations for a new structure that should “be a modern, fireproof structure that will meet all the requirements of the community for twenty-five years to come by which time Huntington will be a thriving city.” As far as financing, the editorial suggests the stockholders use the insurance money, (it was insured for only $5,000), and sale from the ground to build a larger modern building on New York Avenue or Main Street. Further funding could be obtained through donations and subscriptions. Shortly thereafter, the directors of the Opera House Company met and were of the opinion that a new structure, estimated to cost $25,000, would be a losing proposition. Stockholders complained that the demands for a larger, fireproof building with upgraded fixtures and a $500 piano came from people who never put in a penny. Furthermore, stockholders only received one dividend at a rate of five percent but in the meantime have paid assessments at fifteen percent. Consequently, they resolved that a new Opera House not be constructed. March is National Reading Month! By Barbara LaMonicaAssistant Archivist Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Library The Huntington Public Library began as one of the oldest libraries in Suffolk County. The original library’s ledger book contains a copy of a covenant dated June 29, 1759 establishing a subscription, or private, library funded through membership. Rev. Ebenezer Prime, one of the original signers of the covenant, was appointed Library Keeper in charge of membership and the purchasing of books. The library opened with 39 subscribers and a collection of 71 titles, mainly comprising works on divinity and history as stipulated by the covenant. Notably missing were any works of fiction or poetry. The initial subscribers represented some of the prominent and wealthier families in the community including the Platts, Rogers, Scudders, Brushes, Woods, and Ketchams. Evidence that the library was unusual for its time is the acceptance of women as initial subscribers with “equal right with his or her co-subscribers to improve and make use of the library”. The library was the only institution at that time in the town that gave full rights to women. The library survived until 1782 when under the British occupation Rev. Prime’s home was commandeered as British headquarters, and presumably, the library was destroyed during this time. By 1801, a new group was formed to revive the library. Rev. William Schenck was elected chairman, presiding over ministers and prominent families in keeping with the general religious character of the library to date. The new library, situated on the town green had 23 members. Historical documentation is sketchy but it seems this library also dissolved. In 1817 a larger library with 57 subscribers, (many of them heirs to the original members), was formed and housed in the librarian’s home. Station Branch opened in 1929 at 1351 New York Avenue

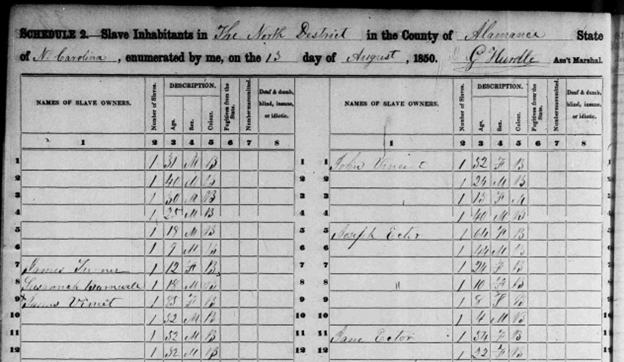

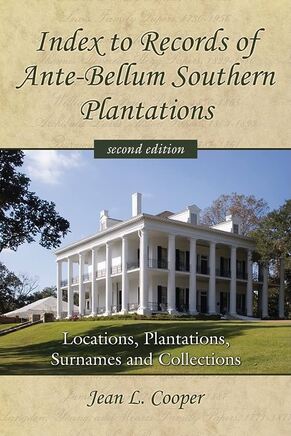

By Barbara LaMonicaAssistant Archivist Finding enslaved African-American ancestors prior to the Civil War can be very difficult. The following article, while not exhaustive, provides information on some basic records critical to this genealogical research. From 1790-1840, the names of slaves were not listed in census records since they were considered property rather than persons. Only the names of the head of household appear with the number of slaves they owned. Enslaved individuals rarely had surnames, many, but not all, took the surname of their owners. However, there are resources that may provide clues to tracking down enslaved ancestors. For the 1850 and 1860 census, the Federal government required that enslaved individuals be recorded separately in “slave schedules”. These schedules do provide more details about these persons including age, sex, color (i.e. mulatto), if they were a fugitive slave, if manumitted, and their physical and mental condition but no names. 1850 Slave Schedule - North Carolina The family papers and records of Southern plantation owners contain an abundance of information such as slave registers, personal correspondence, photographs, and business account books. Sometimes in personal and business letters, the names of slaves may be mentioned. Unfortunately, many plantation records were lost or destroyed during the Civil War. However, most of the surviving papers were often donated to libraries throughout the south. A guide to these papers “Index to Records of Ante-bellum Southern Plantations: Locations, Surnames, and Collections” lists where records can be found, usually university libraries. If the area where the ancestor lived is known one can go to this guide and see if there are existing plantation records. The link below provides further information. Click for Index to Records of Ante-bellum Southern Plantations

Eighteen-seventy is an important turning point for African-American genealogy since the 1870 census is the first one to include the names of former slaves. Therefore, after 1870, a genealogical search of records will be similar to those of European Americans; census reports, births and deaths, service records etc. Other post-Civil war records that can illuminate ancestors’ lives include: -1867 Voter Registration whereby Southern states were mandated to register all African American men over the age of 21 to vote. Since these records include place of birth and name this can be useful to trace back to where person was enslaved. -Records of United States Colored Troops in the Civil War lists the over 186,000 African Americans who served in the Union Army. -The Freedmen’s Bureau Records 1865-1874 known as the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, was established by the War Department. The Bureau supervised abandoned and confiscated property in the South and provided relief and assistance to former slaves. The bureau dispensed clothing and food, operated hospitals and schools; legalized marriages conducted during slavery, and assisted black soldiers and sailors to apply for pensions. The field office records, organized by state, contain personal correspondence from freedmen revealing their experiences in the harsh and still racially divisive society of the post- Civil War South. Here one can find former slaves’ full name, residence, and former masters’ names and plantations. In 1807, Congress outlawed the African slave trade. However, the right to buy and sell slaves and transport them from state to state remained legal. Certain requirements applied to the coastal transport of slaves. The captain of the vessel had to provide a manifest of slave cargo to customs at the port of departure and the point of arrival. This is one of the rare resources prior to 1870 where one can find the name of the enslaved person. In addition to name, the age, sex, color, and residence of owner are provided. Annapolis, Beaufort South Carolina, New Orleans, New York are among the port records with remaining manifests. Below is a link to the Freedmen’s Bureau records and links to other pertinent collections at the National Archives. Many but not all of these records are digitized. Click to link to Freedmen's Bureau records For local assistance contact the African Atlantic Genealogical Society, a member of the Genealogy Federation of Long Island. They are located in the Joysetta & Julius Pearse African American Museum of Nassau County in Hempstead Click for information By Josette LeeThe following is an excerpt from the Huntington Historical Society Quarterly from 1986. To read more from this quarterly and others, make an appointment to visit our Archives!

By Barbara LaMonicaAssistant Archivist

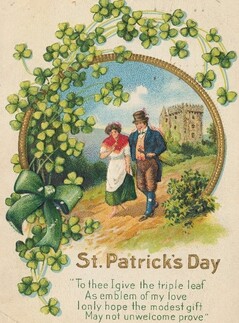

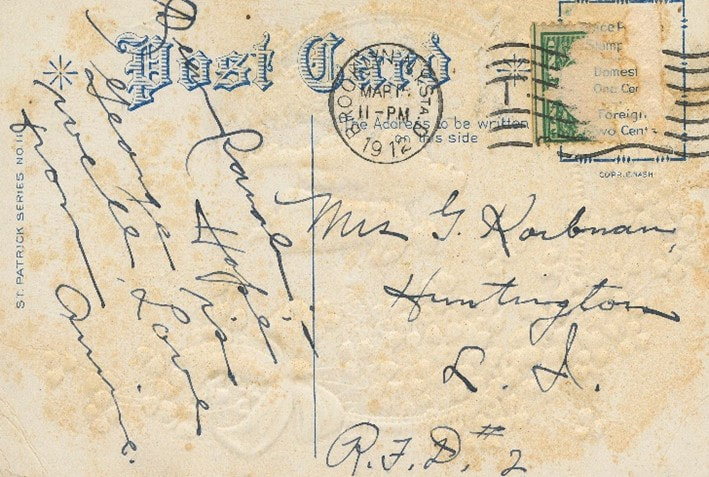

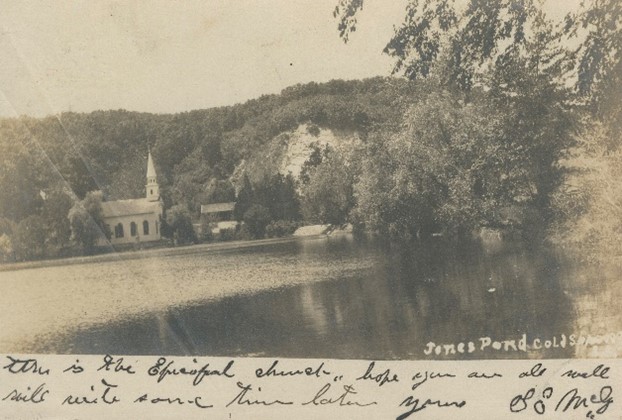

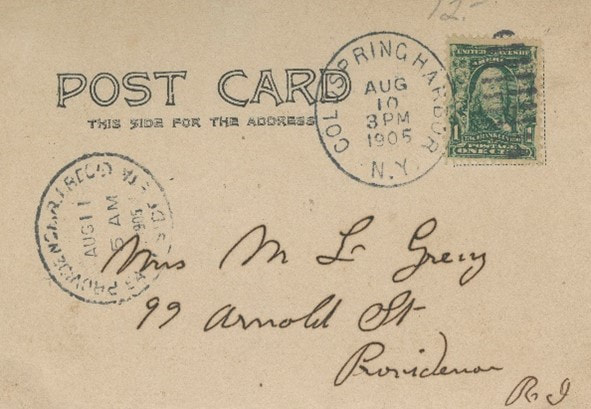

Above, St. Patrick’s Day Postcard, (circa 1907-1910), published by E.Nash, an illustrator and publisher of high quality holiday postcards. The card represents the “Divided Back Era” of early postcards. In March 1907, congress passed an act allowing privately produced postcards to have messages on the left half of the card. The next day the Postmaster-General issued Order No. 146 echoing the congressional act. Prior to 1907, the “Undivided Back Era,” messages were not allowed on the back of postcards and sometimes messages were scribbled on bottom of the image side. Below is an example of “Undivided Back Era” postcard. St. Patrick's Day in America St. Patrick, a Roman Briton born in the 4th century, was allegedly kidnapped by pirates and taken to Ireland as a slave. Little is known about his early life except that he escaped and later returned to convert Ireland to Christianity by establishing monasteries, churches, and schools. Celebrated as the patron saint of Ireland, his feast day was primarily a religious holiday, not a celebration of Irish culture. It was not until the late 19th century when a growing sense of Irish nationalism precipitated the first St. Patrick’s Day parade in Ireland. However, the very first parade in the United States was much earlier. Irish immigrants to the United States essentially changed the religious nature of the day to a secular celebration of “Irishness,” in which all could participate. Boston held its first St. Patrick’s Day parade in 1737 and New York City in 1762. However, there is now some question whether these were the earliest parades. According to a January 21, 2022, article in IrishCentral (https://www.irishcentral.com) by Frances Mulraney, the first St. Patrick’s Day parade was in St. Augustine Florida in 1601. An expenditure log unearthed in a Spanish archive includes notes about the celebration describing St. Augustine residents parading through the city celebrating the saint. Huntington’s first St. Patrick’s Day parade was much, much later. According to the Huntingtonian it was 1935, but according to Newsday it was 1930. The first parades were organized by the Irish American Social Club which met at Finnegan’s. St. Patrick Parade, 1940. Photo by Robert Stone

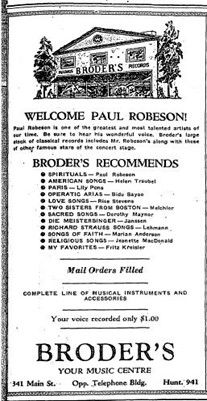

In 1946 Paul Robeson, world-renown African American baritone, actor, and social activist came to Huntington to perform a concert at Toaz Junior High School for the benefit of the Bethel A.M.E. Church’s planned Community Center and Nursery. Roberson was born in 1898 in Princeton New Jersey. His father, a Presbyterian minister, had escaped slavery as a teenager, his mother was a Quaker abolitionist of mixed ancestry. Robeson won a scholarship to Rutgers University where he won 15 varsity letters in baseball, basketball, football, and track. He was Phi Beta Kappa and graduated Valedictorian. Subsequently he graduated from Columbia Law School but later left law practice when a white secretary refused to take dictation from him. He decided to use his artistic talents to promote African-American history and culture in the theater and music. In London, where he won acclaim for his performance in Othello and Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones, Robeson found that racism was not as pronounced in Europe as in the United States. At home, it was difficult to find restaurants to serve him or hotels to house him, and his performances were often surrounded by threats of violence. Long Islander Ad, November 28, 1946 Touted as the greatest baritone in the world Robeson used his talent to interpret Black Spirituals for a world audience, using his performances to speak out against racism and injustice. He performed throughout Europe, the United States and the Soviet Union. Because of his advocacy for organized labor and peace, he became a target for J. Edgar Hoover and the House Un-American Activities Committee and was accused of being a Communist. In 1950, his passport was revoked and he could not travel for eight years. Nevertheless, during this time he published his autobiography Here I Stand, sang at Carnegie Hall and continued to support labor worldwide through transatlantic broadcasts. He retired from public life in 1963 and died at age 77.

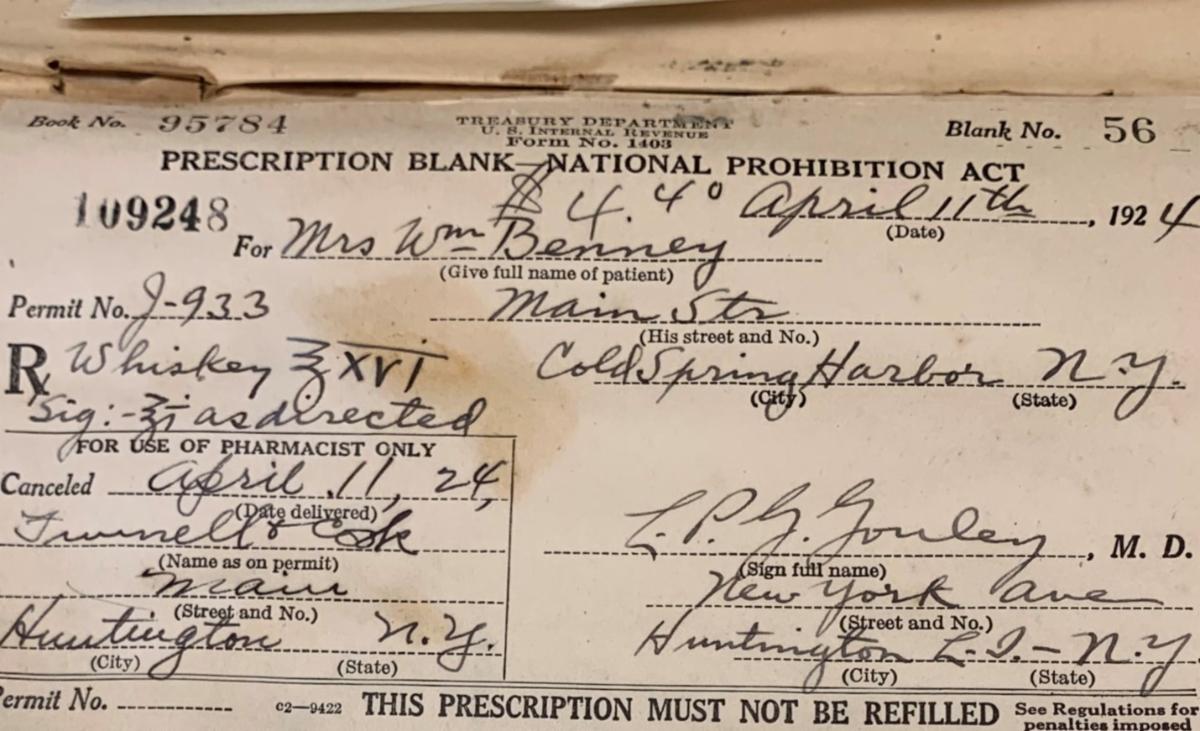

On November 29, 1946, Paul Robeson came to Huntington through the efforts of his acquaintance, Dr. C.V. Granger, a member of the Concert Committee of Huntington and a practicing physician in the town. “Since the days of Huntington and Suffolk County there has never been a concert of this type here before. One may expect men and women from every walk of life to hear this great Negro baritone”, declared Rev. Carpentier of the Bethel A.M.E. Church, (Long Islander, November 28, 1946). During the sold out concert, attended by hundreds of people, Robeson expressed his pleasure at being in Huntington and donating money to the efforts of the A.M.E. Church. In addition to selections from opera and spiritual songs, Robeson performed excerpts from Shakespeare’s Othello. It was truly an historic night for the Town of Huntington. Funnell's Pharmacy, circa 1919 January 12th is Pharmacists Recognition Day and January 19th is the anniversary of the passage of the 18th Amendment to the Constitution in 1919, or Prohibition. The relation between the two is quite interesting.

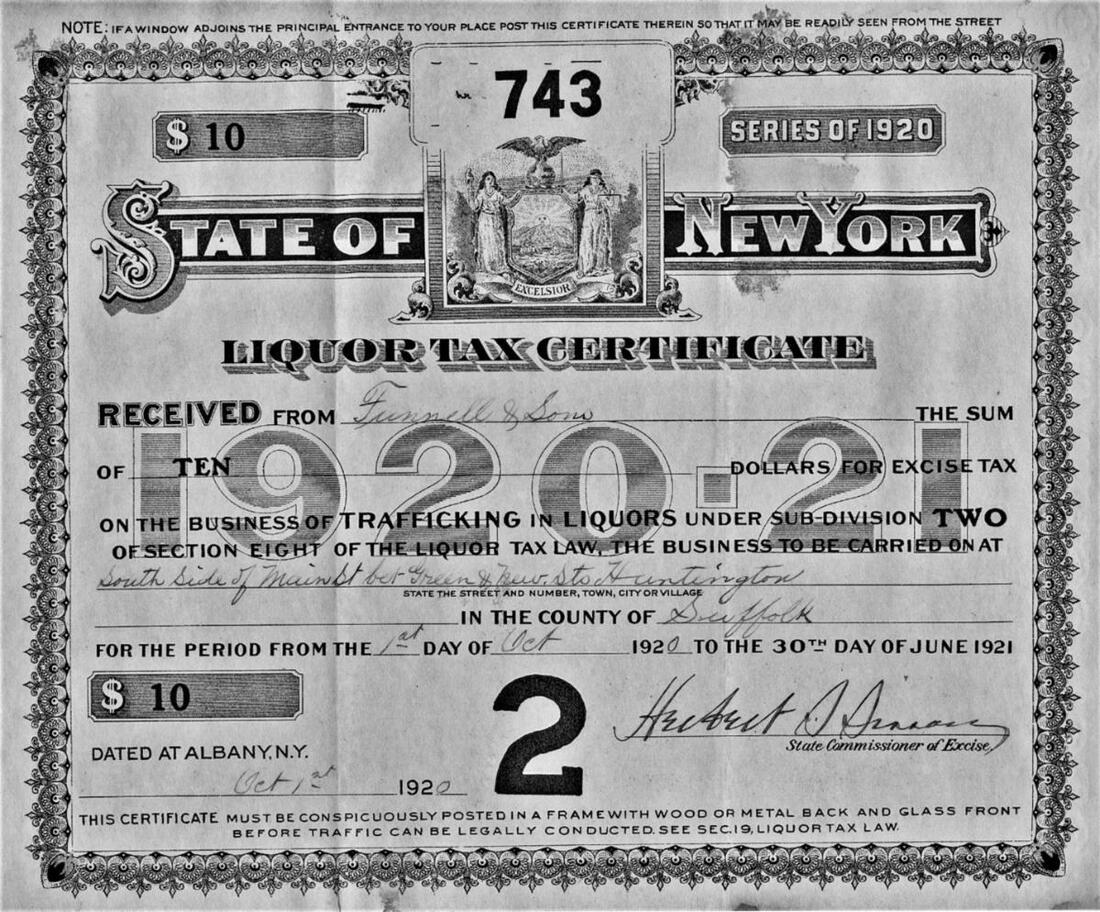

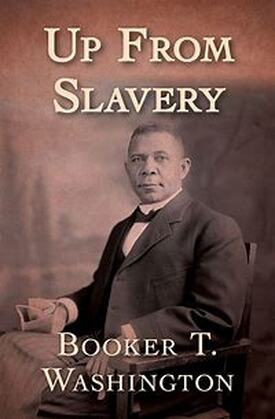

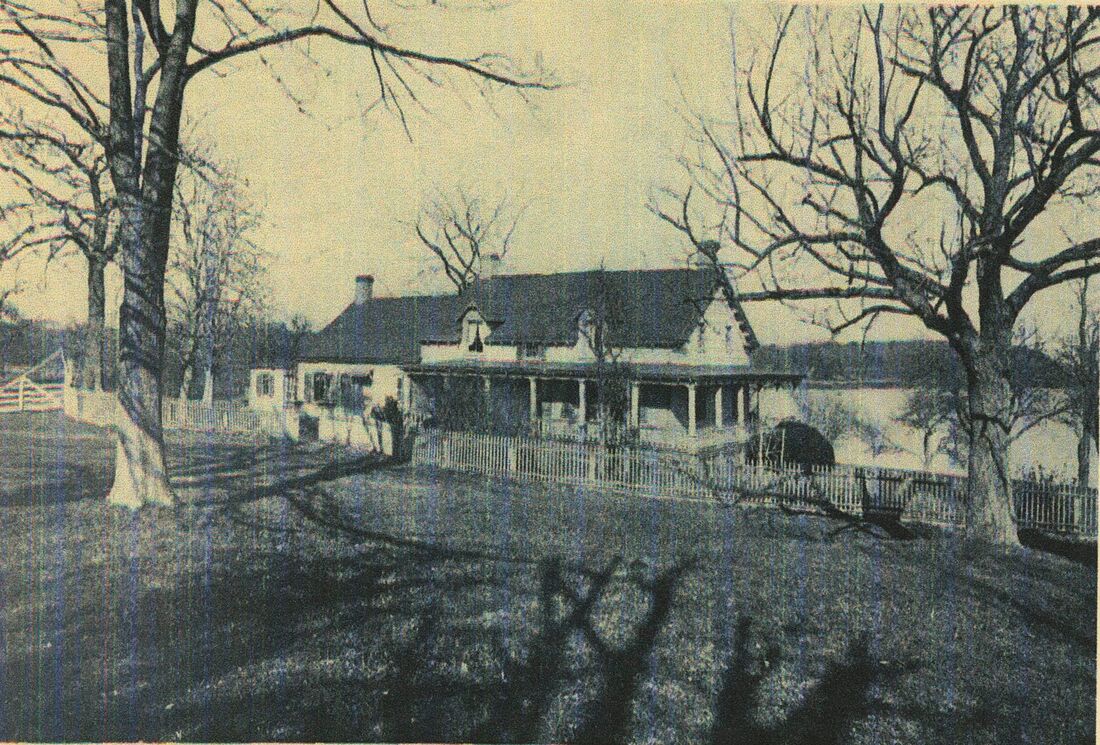

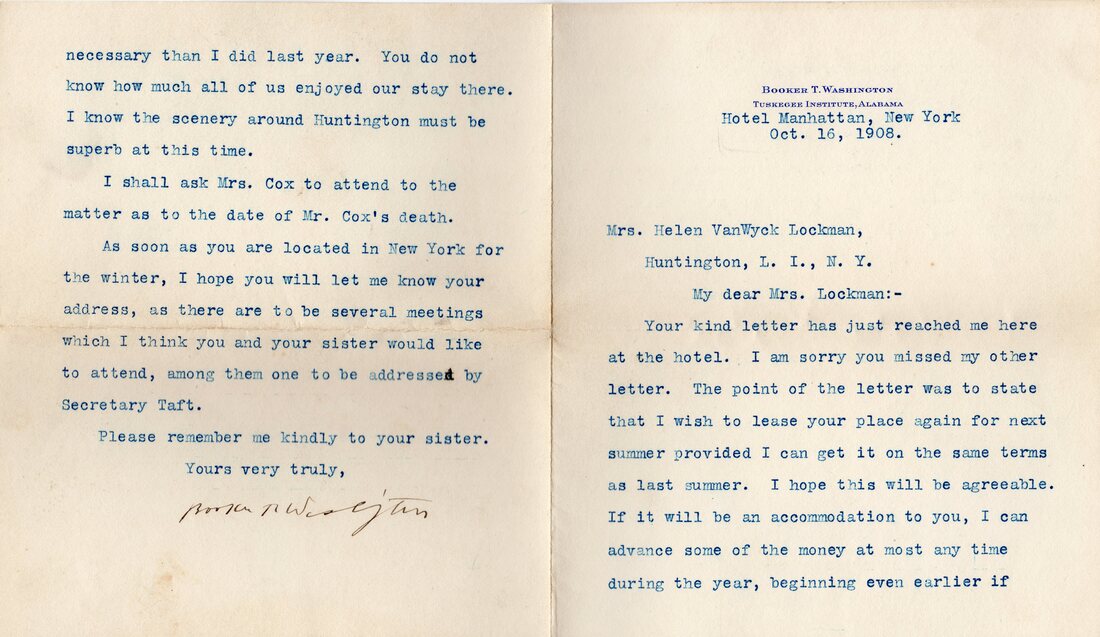

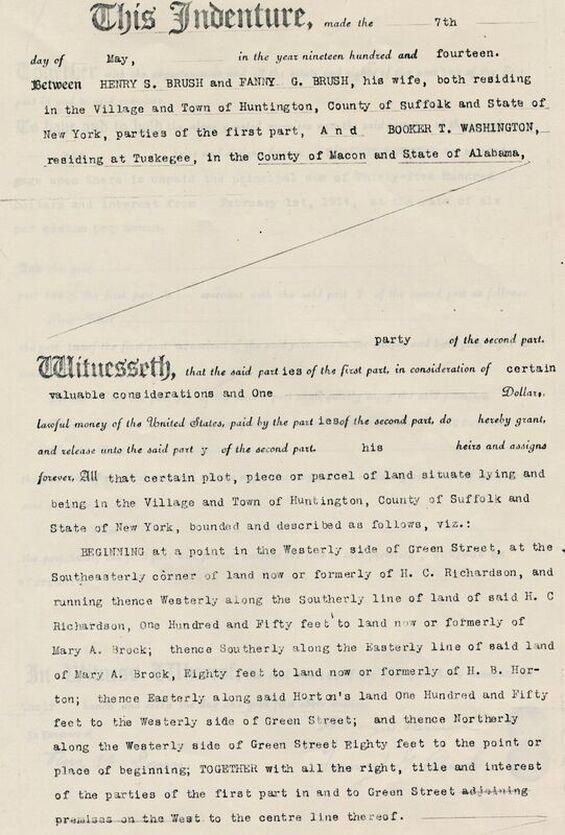

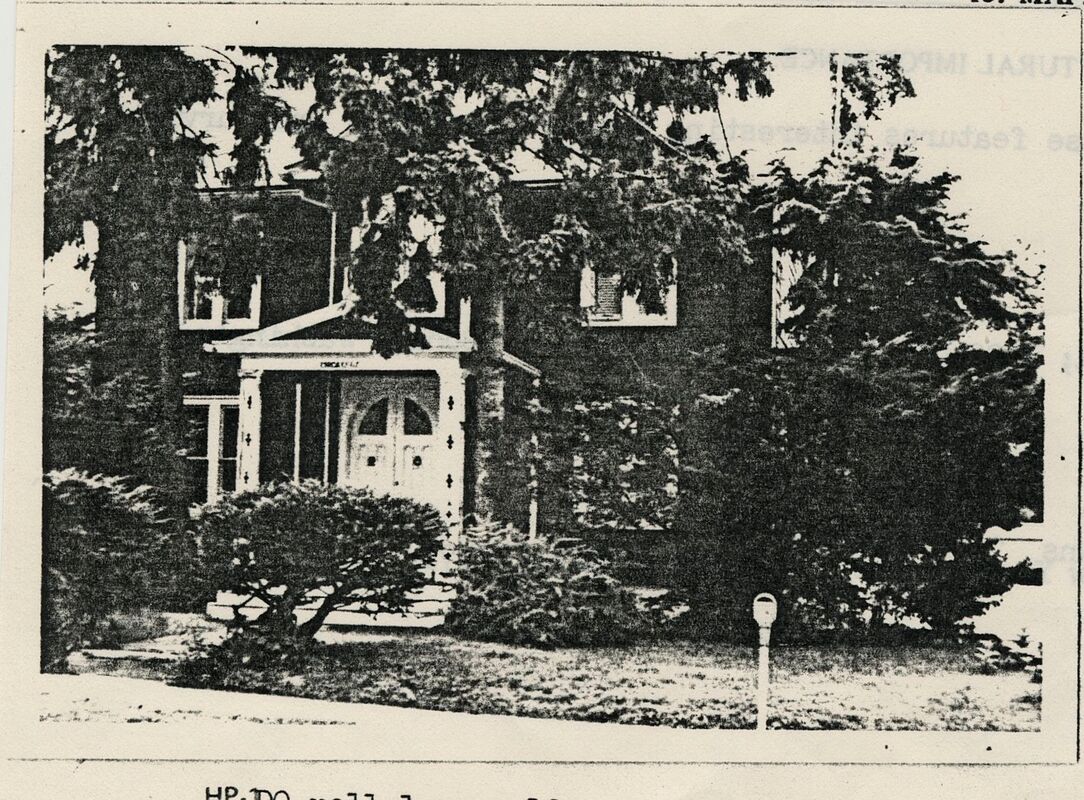

Contrary to common belief, the 18th Amendment to the Constitution did not prohibit the consumption of alcohol. If you owned a generous liquor cabinet in your home, you were permitted to drink at home or at a friend’s house. Besides storing liquor at home, you could transport it from an old residence to a new residence. The bill only made it illegal to manufacture, import, and distribute alcohol, and there were exemptions for religious, industrial, and medicinal purposes (as doctors had often prescribed alcohol as a tonic for a variety of complaints from anxiety to influenza). Since alcohol was permitted for “medicinal” purposes, doctors could proscribe and pharmacists could fill prescriptions for alcohol or tonics with alcohol content. During the prohibition period, (the law went into effect in 1920 and was repealed in 1933) the number of registered pharmacists nearly tripled in New York state as this became a popular way to obtain liquor. With a physician’s prescription, patients could legally buy a pint of hard liquor every ten days. Prohibition provided a booming business for pharmacies. For example, Walgreens grew from approximately 20 outlets in 1919 to over 500 by 1929. Below are some illustrations of Liquor Tax Certificate, and prescriptions from Funnell’s Drug Store, the first pharmacy in Huntington, founded in 1853. Funnell’s was on the south side of Main Street between New and Green Streets. Born a slave in 1856 in Virginia, Booker T. Washington rose to become a renowned spokesperson for African Americans. Washington’s belief that African Americans could advance themselves through education in the trades and industrial arts prompted him to establish the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama in 1881. Washington was well respected as an orator and author. Of his 14 books, his autobiography “Up from Slavery” (published in 1901) became the most well-known. His writings gained him national influence in education and politics and led him to become an advisor and friend to Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft. In 1901, Washington was invited to dine with Roosevelt at the White House, a radical invitation that led to much outcry from southern politicians and press. WASHINGTON IN HUNTINGTONWhen the school session ended at Tuskegee, Booker T. Washington would head north to Long Island for summer vacation and fundraising. Before purchasing a home in Fort Salonga, Washington summered at the Van Wyck Farm in Lloyd Harbor. Van Wyck Farm in Lloyd Harbor, which no longer exists In 2021, a descendent of the Lloyd Harbor Van Wyck family donated three letters from Washington that refer to his stay on the Van Wyck Farm. The letters are now part of the Society's collection and provide insight into his time there. While in Huntington, Washington gave several talks at the local Opera House, as well as a commencement speech at Northport High School. He also taught Sunday School at Bethel AME Church. Most locals know that Washington purchased a property in Fort Salonga, but it is less commonly known that he also acquired a house in Huntington Village. According to this deed dated May 7, 1914, Henry and Fanny Brush transferred property at 43 Greene Street, Huntington to Booker T. Washington. The house still stands today and is the location of Finley’s Restaurant. 43 Green Street, today Finley's Restaurant It is not known what Washington planned to do with the home as he passed away within a year of purchase.

|

AuthorThis blog has been written by various affiliates of the Huntington Historical Society. Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

Become a Member

Donate Today!

Signup For Our Newsletter

Thanks for signing up!

© Huntington Historical Society. All rights reserved.

The Huntington Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the Town of Huntington for its steadfast support.

The Huntington Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the Town of Huntington for its steadfast support.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed