By Emily WernerHHS Curator & Collections Manager In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, many professional weavers immigrated from Germany, Scotland, Ireland, or England after lengthy apprenticeships in specialized weaving techniques, such as damask or carpet weaving. Known as “fancy weavers,” they settled in small towns along the east coast, including New York, and adapted their specialized knowledge to weaving “bed carpets” or “carpet coverlets.”

Professional weavers were almost exclusively men. Although women continued to play a vital role in supporting textile production by preparing the raw materials and finishing the cloth after it was woven, few women actually became professional weavers themselves. Many professional weavers were not only weavers, but also worked other jobs, such as farming, to support themselves throughout the year. They set up workshops at home or at another established location, where customers could bring their design preferences and homespun yarn for the textiles they were commissioning. Professional weavers made coverlets for specific customers, typically women, and wove her name and the date into the corner block or along the border of the coverlet. Occasionally weavers included other phrases as well, such as their name, a town name, or even the name of the pattern. The text was almost always woven lengthwise into the coverlet (in the warp direction). Because of the reversibility of double cloth fabric, the text is legible on one side of the coverlet and appears reversed on the other. The practice of naming and dating coverlets in this manner is thought to have originated on Long Island. Long Island coverlets were woven in a weave structure called double cloth. Double cloth coverlets are created by weaving two layers of fabric simultaneously, each layer intersecting at specific points to produce the pattern. The fabric is reversible, with one side predominantly dark and the other side predominantly light. The dark yarn was indigo-dyed wool, usually provided by the customer, while the light yarn was undyed machine-spun cotton. Because they used twice as much yarn as other types of fabrics and required great skill and technology to weave, double cloth coverlets were some of the most costly and prized textiles in nineteenth-century American homes. Visit our new exhibit, From Farm to Fabric: Early Woven Textiles of Long Island, to find out even more about these beautiful textiles! Open through September 17, 2023 at the Soldiers & Sailors Memorial Building at 228 Main Street, Huntington. This exhibit was part of a collaboration with Preservation Long Island to highlight the importance of Long Island’s early weaving practices and industry. Their exhibit, Blanket Statements: Long Island’s Early Weaving Industry, explores Long Island’s early textile industry and the broader historical events that shaped its growth during the first half of the nineteenth century. Open through October 8, 2023 at the Preservation Long Island Gallery at 161 Main Street, Cold Spring Harbor. Photo captions: Geometric double cloth coverlet, woven for Phebe Titus, December 21, 1817. Attributed to Mott Mill. Huntington Historical Society, 1987.20 / Figured and Fancy double cloth coverlet, woven for Mary H. Wood, 1839. Huntington Historical Society, 1966.7.1.

0 Comments

By Barbara LaMonicaAssistant Archivist

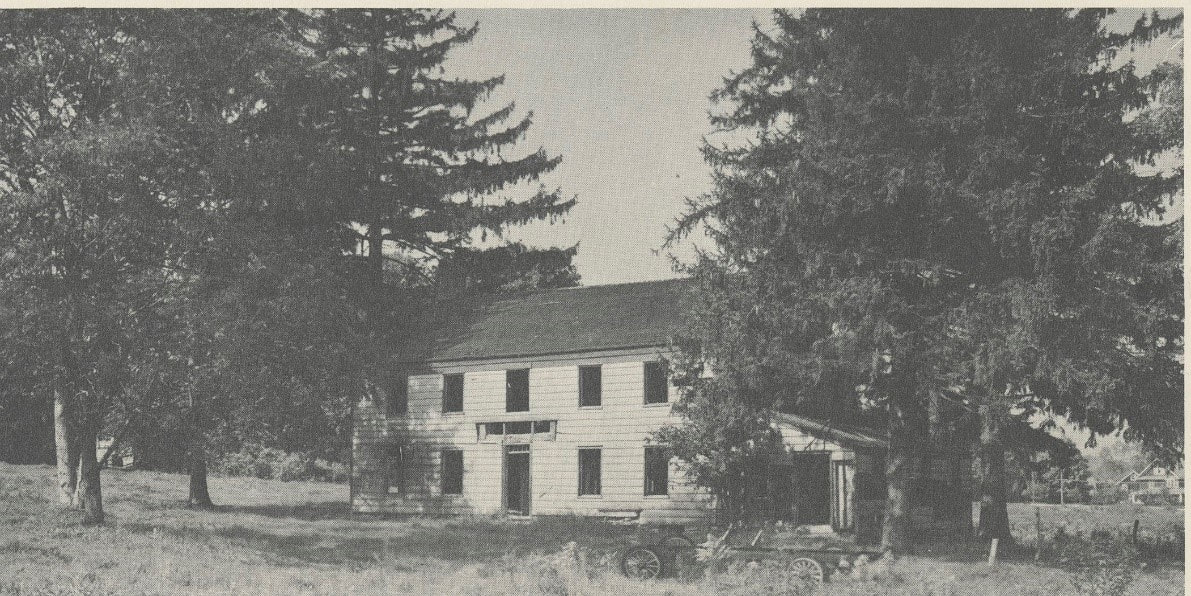

This law addressed the gap in care of the poor created by Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries, as the monasteries had been the main source of charity. The Elizabethan law established the precept of local control, meaning each village had the responsibility for its own poor. Local officials had the power to raise taxes and appoint an overseer to administer the charity funds. A later law, The Law of Settlement and Removal, empowered villages to expel persons back to their home village should they become dependent, insuring that “no vagabonds or beggars allowed. “ As early as 1687, the Province of New York passed a law mandating towns and counties take care of their own poor. Pre and post revolution New York continued to establish statutes such as binding out poor children as apprentices and servants, and the establishment of poor or work houses. Eventually children were removed from these institutions and placed in orphanages. According to Huntington Town Records, the town trustees who acted as overseers evaluated destitute residents on a case-to-case basis. Eventually separate overseers were appointed. These individuals came from prominent Huntington families. Town overseer records show in 1763 the first overseers came from the Brush, Platt, and Wood families. Over the years such personages as William Woodhull, Solomon Ketchum, John Rogers, Israel Scudder, Hiram Baylis served multiple terms. As an interesting aside, it was not until 1921 that the first woman overseer, Maude E. Henschell, was elected. A Brooklyn Times Union article dated December 29, 1921 took note of her reelection: “There previously had been grave doubts as to whether the office could be fulfilled successfully by a woman...the women and children with whom she came in contact find in her a friend ready to aid them and many of the kindness have been done by her outside of her official duties. She has ably proved that some features connected with the office can be looked after by a woman better than a man.” A proportion of funds raised by the town from taxes, licensing fees and fines were distributed to the overseers. Traditionally, destitute able-bodied residents were placed with families to do household chores or farm work in exchange for room and board. The families were expected to provide food, clothing and shelter, and medical care. Some professionals were paid by the town as records show that during the early 1800s Dr. Kissam received $35 a year to attend the poor. Children whose families could not maintain them or who were orphaned were placed as apprentices. The town also paid for younger children to be boarded with families. Widows were often placed with families as well, as an entry in the records of the Huntington Overseers of the Poor dated October 29 1736 states: “M. Wickes President of the Trustees-I desire you to Lett the Carrel here of Isaac brush have the Sum of Thirty four Shill it being the third payment for my keeping the widdow Jones in so doing you will Oblige your friend Benjamen Soper. Over time responsibility for the poor slowly evolved toward a more centralized model. By the mid-1800s with the growth in population, it was becoming obvious that the practice of placing the poor in homes was becoming unwieldly and inefficient. In 1821, It was determined that the poor should be placed in one location, and by 1824, the town purchased a farm on the the village green to house the poor. Those who refused to go would be denied any further aid. A manager was hired to work the farm with the residents. Proceeds from the farm went to support the house. Concurrently New York State passed a law requiring each county to construct a poorhouse. By 1871, a poorhouse was constructed in Yaphank and the town resolved to relocate the poor there, but Town overseers continued to provide for widows and families in their own homes. Eventually however care of the poor would be transferred from the local level to county and state. The last Overseer or Superintendent of the Poor was in 1929. In 1929, the year of the Great Depression, New York State enacted a repeal of the poor laws in order to expand responsibility for the poor from a local level to more centralized control with uniform standards throughout the state. Previous laws were deemed a hodgepodge of incoherent rules and amendments differing from town to town. Now each county would have a Superintendent of the Poor who had control over local overseers. The new state laws emphasized in home care and rehabilitation, with special concern for child welfare. The New Deal and the Social Security Act of 1935 solidified care for the poor and unemployed in Federal and State programs thus completing the transfer from town/local control to county, state and federal levels. For more detailed study see:

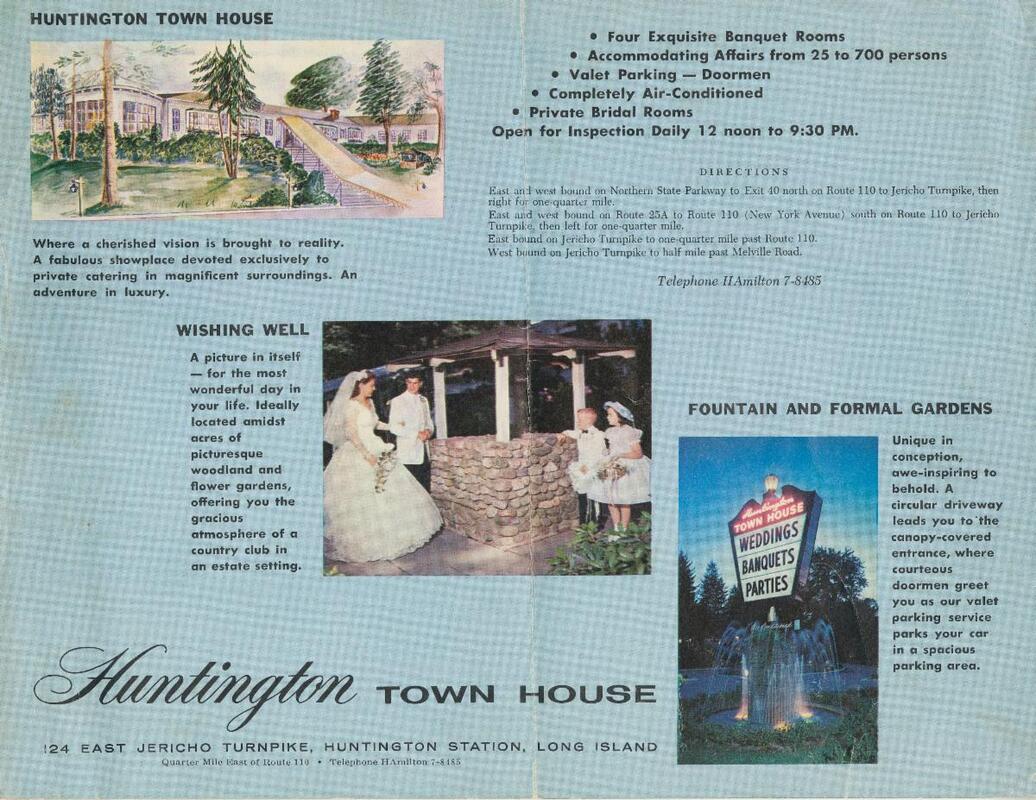

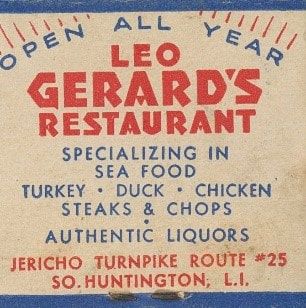

Bond, Elsie M. “New York’s Public Welfare Law”. Social Service Review, vol. 3, 1929, pp.412-21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30009380 Lindsay, Samuel McCune, “Social and Labor Legislation”. American Journal of Sociology, vol. 35, no.6. 1930 pp.967-81. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2766847 Huntington’s Legal History, Antonia S. Mattheou, Town Archivist, Town of Huntington Joanne Raia Archives. Companion publication to exhibition at the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Building, March 1-May 15, 2023. Stuhler, Linda S. “A Brief History of Government Charity in New York (1603-1900). VCU Libraries Social Welfare History Project. https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu Town of Huntington Records of the Overseers of the Poor Addendum 1729-1843. Rufus B. Langhans Huntington Town Historian, Town of Huntington 1992. By Barbara LaMonicaAssistant Archivist  For nearly 50 years, the Huntington Town House reigned as a celebrated venue for weddings, proms, bar mitzvahs, and anniversary parties. Politicians and celebrities such as the Beach Boys, Steve Levy, Hillary Clinton, and Donald Trump held events there. More importantly, the Town House engenders memories for the thousands of people whose milestone celebrations were held under its crystal chandeliers. The evolution of the Town House begins in the late nineteenth century with a restaurateur and hotelier family, the Gerards. William Gerard operated hotels in Cold Spring Harbor-the Laurelton on the west side of the harbor, and after he sold the Laurelton in 1880, he acquired the Glenda, Matchbook Covers for Gerard's a castle built in 1853 on the east side of the harbor. His son Leo, born in 1892, grew up in the hotels, and eventually followed in his father’s footsteps. Initially Leo became manager at the Huntington Yacht Club in 1927, and then in 1932 he opened Gerard’s Restaurant on 25A in Cold Spring Harbor (later to become The Moorings Restaurant). Gerard’s Restaurant became so popular that even after expanding the building he still had to turn customers away. This prompted him to look for other locations to accommodate larger crowds. In March 1937, Leo purchased the 5-acre Bruns estate on the south side of Jericho Turnpike ½ mile east of Route 110. The estate home had a large dining room that could seat over 100 people in addition to several bedrooms. Leo Gerard added a dance floor, a taproom, and a cocktail lounge.  In 1957, Gerard, ready to retire after a solidly successful run, sold the property to Thomas Manno, who in anticipation of the coming baby boom generation, turned it into a strictly catering business and christened it the Huntington Town House. Manno expanded banquet facilities to 11 rooms. Multiple kitchens equipped with machines could turn out 5,000 meatballs in one hour, and high-pressure mashed potato hoses could gush out 2,000 potato rosettes in a comparable amount of time. The property comprised 20 acres with parking spaces for 2,000 cars. Now renown as the only catering facility of its kind, the Town House attracted customers from all over the Island as well as Queens, Manhattan, the Bronx, and Westchester. Manno had plans to build a conference center with lodgings on the property, but after he passed away, his widow sold the Town House to Rhona Silver in 1997 for 7.6 million dollars. Silver was the most flamboyant and successful Town House owner. She reached icon status as the “queen of catering” presiding over a business that in addition to weddings, night after night hosted charity dinners and corporate events. It was even the site of a concert by the rapper 50 Cent. She specialized in creating spectacle and fantasy, a bride and groom arriving in the grand ballroom in a coach drawn by two white horses, or a couple landing on the lawn in a hot air balloon. She was in demand for offsite catering as well, such as catering an affair for the prime minister of Israel and being the only caterer allowed inside Mar-a-Lago. As a child, she grew up in her family’s catering business in the Bronx, and later opened a catering business in space she rented in Temple Beth El in Cedarhurst where she was known as the only Glatt Kosher caterer. Silver had plans to construct a lodging and conference center at the Town House which had preliminary approval when Manno had first proposed the idea. However, these plans never came to fruition as Silver sold the Town House to Lowes for $38.5 million in 2007. She suddenly found herself mired in several lawsuits. The real estate company sued her for commissions and her half-brother sued her claiming he owed half the Town House business. Silver then initiated her own lawsuit suing her boyfriend, Barry Newman, real estate developer, for $25.9 million claiming he forged her name on documents for the sale and ripped her off for millions leaving her destitute. Newman claims he loaned her millions over the years for the business but it really supported her lavish lifestyle. He claims the proceeds from the sale were used to pay off debtors. Who knows what really happened? Unfortunately, Silver died of a heart attack in 2017, with the law suits still unresolved. The Huntington Town House, a repository of memories for a generation, was ultimately demolished in 2011 to be replaced by Target. By Toby Kissam

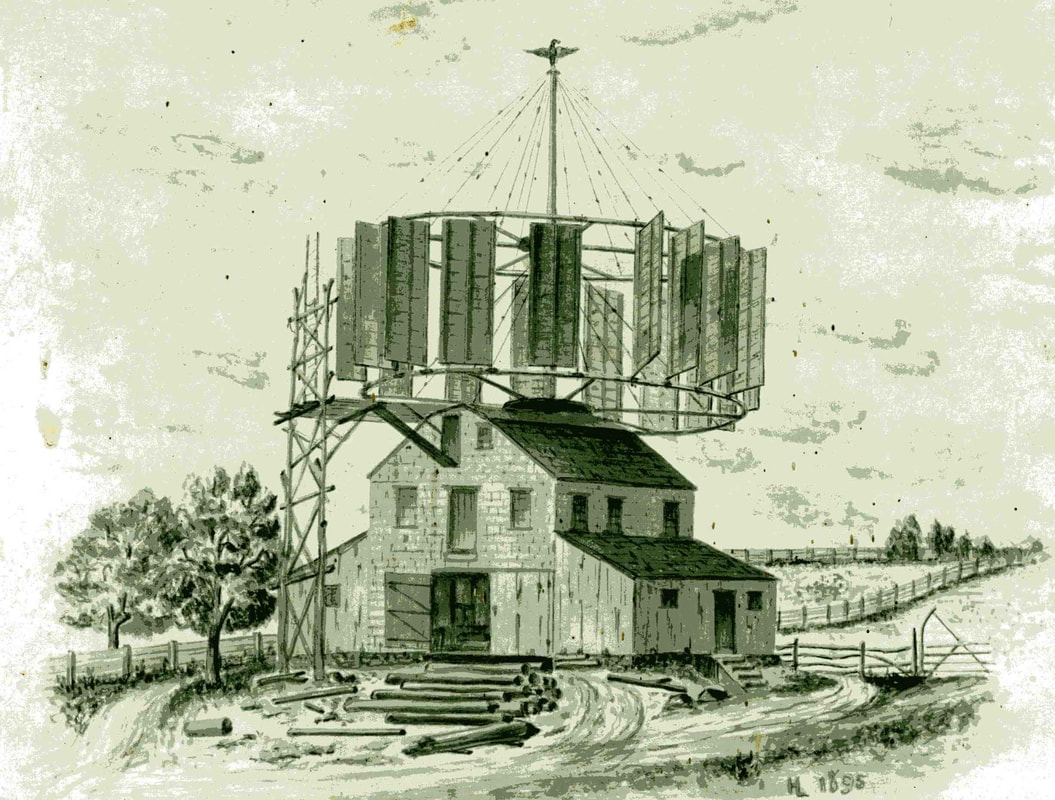

The surviving 1825 "Eagle" that stood above the "sails" on the Daniel Sammis Saw Mill. The year is 1826:

Daniel Sammis (1787-1869), a 5th generation Sammis in Huntington, erected a large and unusual saw mill, powered by wind, in 1825. It was described as “The most conspicuous building in the place.” One of his clients was Carman Smith. A circular dated December 21, 1826, and issued by the proprietor, stated the purpose for which the mill was built. Sammis designed and built this unique mill, possibly from earlier Dutch examples in New Amsterdam. Built on the ridge, north of Main Street, between West Neck Road and Wall Street, in 1846 the mill was moved closer to Main Street into what is today a municipal parking lot across from the Post Office. In 1867, a hurricane blew off the circular carousel structure that powered the mill and its wind directional, breaking one of the eagle’s wings. The building was used after as a barn until it was torn down in the early 20th century. Henry Lockwood (1838-1901), a grandson of Daniel Sammis, whose family owned the marble foundry next door and whose mother was the daughter of Daniel Sammis, recalled when he and his friends, as young boys, would climb the circular structure and “ride the wind.” Although considered dangerous, reportedly no one was seriously injured. Late in his life, Henry drew the sketch of the mill for an article in the Brooklyn Eagle. In 1923, the Lockwood House was torn down and the “Eagle,” although damaged during the 1867 hurricane, was donated to the Huntington Historical Society and is today the symbol for the Society. You can visit this almost 200-year-old artifact at the History and Decorative Arts Museum in the Soldiers & Sailors Memorial Building on Main Street. The 1895 sketch of the saw mill done by the grandson of Daniel Sammis, Henry Lockwood, for the article in the Brooklyn Eagle.

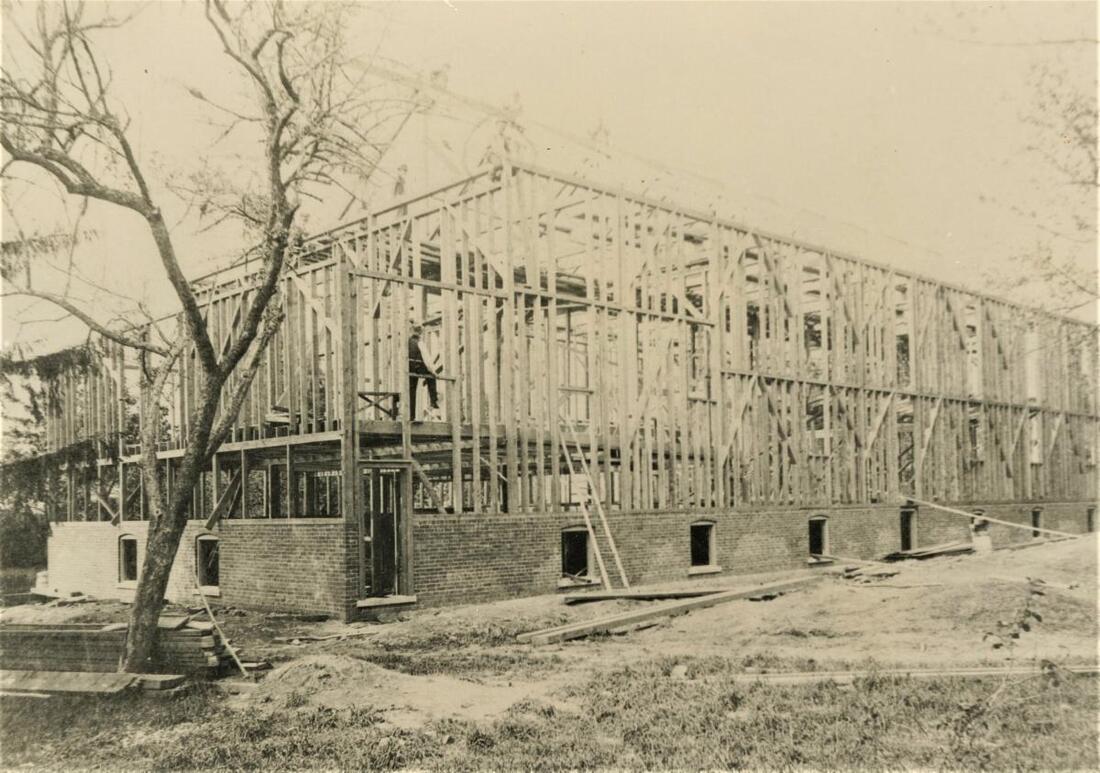

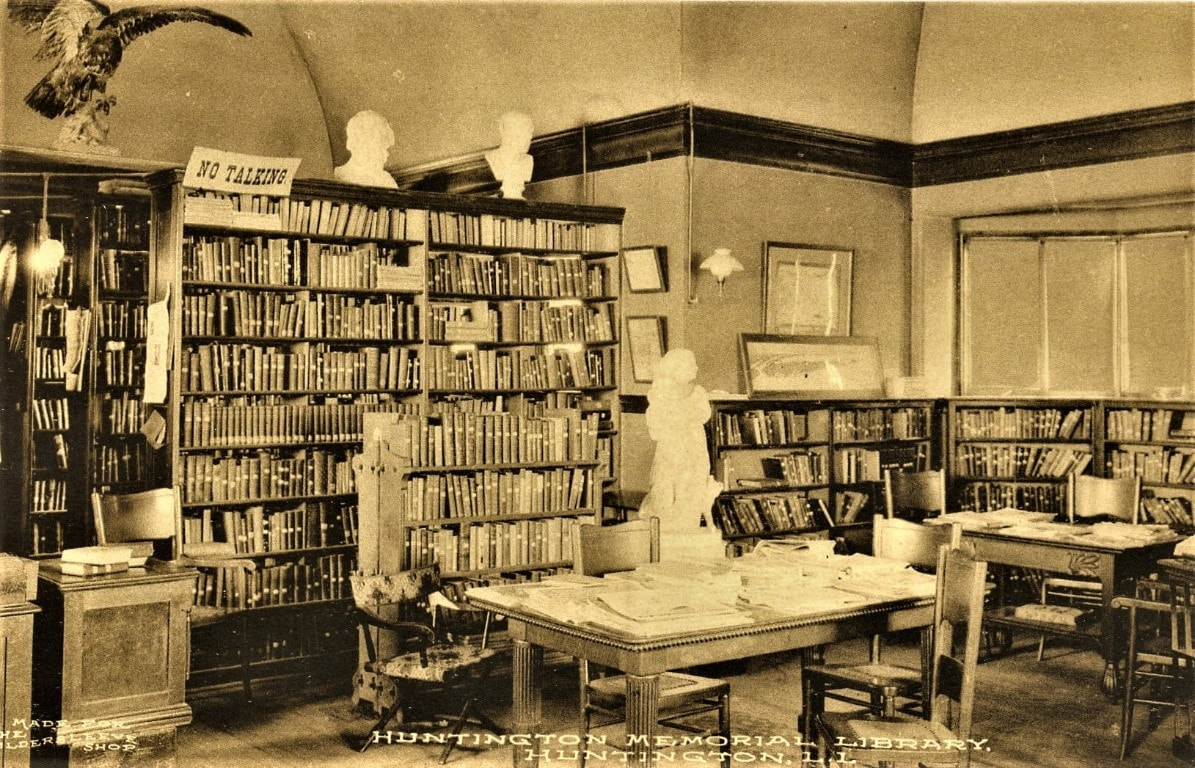

by Barbara LaMonicaAssistant Archivist Built for $9,000 in 1892 by a consortium of local businessmen, the Huntington Opera House was a nexus for local as well as outside talent, distinguished lecturers, concerts, high school graduations, poultry and horticulture shows and political rallies. However nary an opera was performed there. In the 19th century, theaters were often called opera houses because opera was seen as carrying a hint of cultural sophistication, while theater was still considered somewhat disreputable. In 1910, the Opera House burned to the ground. The fire, discovered around midnight is believed to have started in a cloakroom. The wooden structure burned with such ferocity that it was considered a miracle the rest of the block, consisting of various stores, was not also consumed. This was thanks to the efforts of the Huntington, Halesite, Fairground, Cold Spring Harbor, and Centerport fire departments. The firefighters laid half a dozen lines of hose to wet down the adjoining buildings, thus keeping the fire contained. Some buildings were saved by a fortuitous northwest wind that carried the sparks far above and away from the street. A March 18, 1910 editorial in the Long Islander advocates strongly for a new opera house as “Such a large, rapidly growing and prosperous village as Huntington cannot do long without an Opera house.” The editorial continues with recommendations for a new structure that should “be a modern, fireproof structure that will meet all the requirements of the community for twenty-five years to come by which time Huntington will be a thriving city.” As far as financing, the editorial suggests the stockholders use the insurance money, (it was insured for only $5,000), and sale from the ground to build a larger modern building on New York Avenue or Main Street. Further funding could be obtained through donations and subscriptions. Shortly thereafter, the directors of the Opera House Company met and were of the opinion that a new structure, estimated to cost $25,000, would be a losing proposition. Stockholders complained that the demands for a larger, fireproof building with upgraded fixtures and a $500 piano came from people who never put in a penny. Furthermore, stockholders only received one dividend at a rate of five percent but in the meantime have paid assessments at fifteen percent. Consequently, they resolved that a new Opera House not be constructed. March is National Reading Month! By Barbara LaMonicaAssistant Archivist Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Library The Huntington Public Library began as one of the oldest libraries in Suffolk County. The original library’s ledger book contains a copy of a covenant dated June 29, 1759 establishing a subscription, or private, library funded through membership. Rev. Ebenezer Prime, one of the original signers of the covenant, was appointed Library Keeper in charge of membership and the purchasing of books. The library opened with 39 subscribers and a collection of 71 titles, mainly comprising works on divinity and history as stipulated by the covenant. Notably missing were any works of fiction or poetry. The initial subscribers represented some of the prominent and wealthier families in the community including the Platts, Rogers, Scudders, Brushes, Woods, and Ketchams. Evidence that the library was unusual for its time is the acceptance of women as initial subscribers with “equal right with his or her co-subscribers to improve and make use of the library”. The library was the only institution at that time in the town that gave full rights to women. The library survived until 1782 when under the British occupation Rev. Prime’s home was commandeered as British headquarters, and presumably, the library was destroyed during this time. By 1801, a new group was formed to revive the library. Rev. William Schenck was elected chairman, presiding over ministers and prominent families in keeping with the general religious character of the library to date. The new library, situated on the town green had 23 members. Historical documentation is sketchy but it seems this library also dissolved. In 1817 a larger library with 57 subscribers, (many of them heirs to the original members), was formed and housed in the librarian’s home. Station Branch opened in 1929 at 1351 New York Avenue

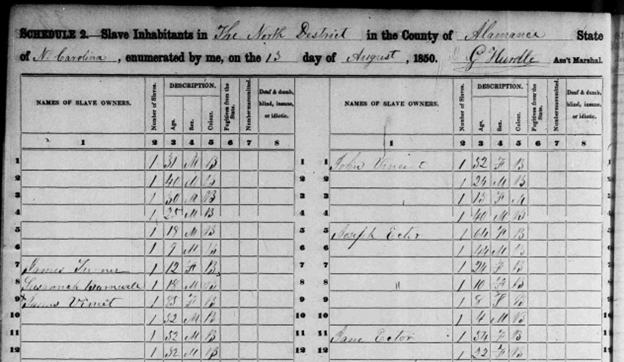

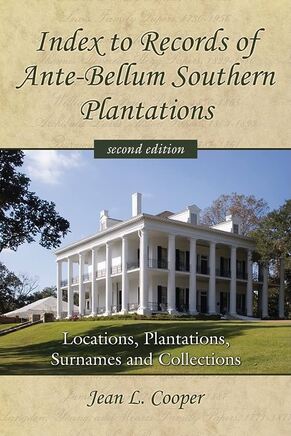

By Barbara LaMonicaAssistant Archivist Finding enslaved African-American ancestors prior to the Civil War can be very difficult. The following article, while not exhaustive, provides information on some basic records critical to this genealogical research. From 1790-1840, the names of slaves were not listed in census records since they were considered property rather than persons. Only the names of the head of household appear with the number of slaves they owned. Enslaved individuals rarely had surnames, many, but not all, took the surname of their owners. However, there are resources that may provide clues to tracking down enslaved ancestors. For the 1850 and 1860 census, the Federal government required that enslaved individuals be recorded separately in “slave schedules”. These schedules do provide more details about these persons including age, sex, color (i.e. mulatto), if they were a fugitive slave, if manumitted, and their physical and mental condition but no names. 1850 Slave Schedule - North Carolina The family papers and records of Southern plantation owners contain an abundance of information such as slave registers, personal correspondence, photographs, and business account books. Sometimes in personal and business letters, the names of slaves may be mentioned. Unfortunately, many plantation records were lost or destroyed during the Civil War. However, most of the surviving papers were often donated to libraries throughout the south. A guide to these papers “Index to Records of Ante-bellum Southern Plantations: Locations, Surnames, and Collections” lists where records can be found, usually university libraries. If the area where the ancestor lived is known one can go to this guide and see if there are existing plantation records. The link below provides further information. Click for Index to Records of Ante-bellum Southern Plantations

Eighteen-seventy is an important turning point for African-American genealogy since the 1870 census is the first one to include the names of former slaves. Therefore, after 1870, a genealogical search of records will be similar to those of European Americans; census reports, births and deaths, service records etc. Other post-Civil war records that can illuminate ancestors’ lives include: -1867 Voter Registration whereby Southern states were mandated to register all African American men over the age of 21 to vote. Since these records include place of birth and name this can be useful to trace back to where person was enslaved. -Records of United States Colored Troops in the Civil War lists the over 186,000 African Americans who served in the Union Army. -The Freedmen’s Bureau Records 1865-1874 known as the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, was established by the War Department. The Bureau supervised abandoned and confiscated property in the South and provided relief and assistance to former slaves. The bureau dispensed clothing and food, operated hospitals and schools; legalized marriages conducted during slavery, and assisted black soldiers and sailors to apply for pensions. The field office records, organized by state, contain personal correspondence from freedmen revealing their experiences in the harsh and still racially divisive society of the post- Civil War South. Here one can find former slaves’ full name, residence, and former masters’ names and plantations. In 1807, Congress outlawed the African slave trade. However, the right to buy and sell slaves and transport them from state to state remained legal. Certain requirements applied to the coastal transport of slaves. The captain of the vessel had to provide a manifest of slave cargo to customs at the port of departure and the point of arrival. This is one of the rare resources prior to 1870 where one can find the name of the enslaved person. In addition to name, the age, sex, color, and residence of owner are provided. Annapolis, Beaufort South Carolina, New Orleans, New York are among the port records with remaining manifests. Below is a link to the Freedmen’s Bureau records and links to other pertinent collections at the National Archives. Many but not all of these records are digitized. Click to link to Freedmen's Bureau records For local assistance contact the African Atlantic Genealogical Society, a member of the Genealogy Federation of Long Island. They are located in the Joysetta & Julius Pearse African American Museum of Nassau County in Hempstead Click for information By Josette LeeThe following is an excerpt from the Huntington Historical Society Quarterly from 1986. To read more from this quarterly and others, make an appointment to visit our Archives!

By Barbara LaMonicaAssistant Archivist

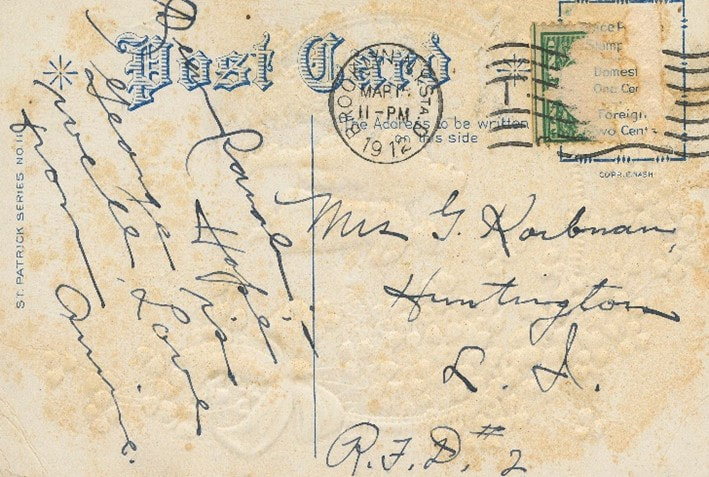

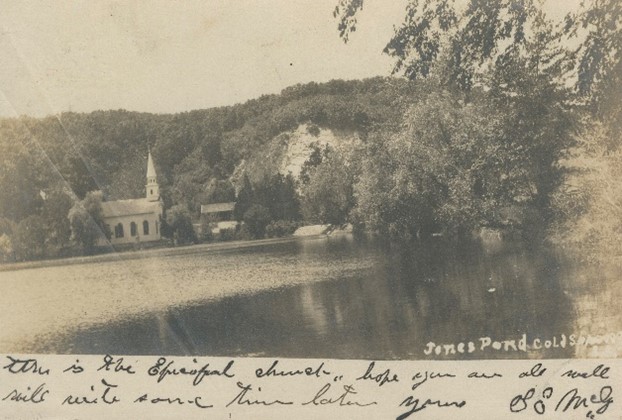

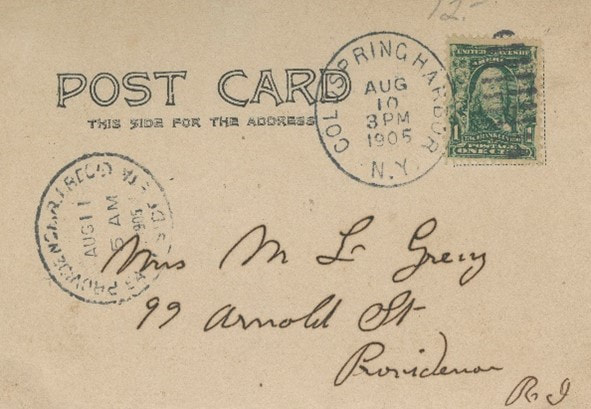

Above, St. Patrick’s Day Postcard, (circa 1907-1910), published by E.Nash, an illustrator and publisher of high quality holiday postcards. The card represents the “Divided Back Era” of early postcards. In March 1907, congress passed an act allowing privately produced postcards to have messages on the left half of the card. The next day the Postmaster-General issued Order No. 146 echoing the congressional act. Prior to 1907, the “Undivided Back Era,” messages were not allowed on the back of postcards and sometimes messages were scribbled on bottom of the image side. Below is an example of “Undivided Back Era” postcard. St. Patrick's Day in America St. Patrick, a Roman Briton born in the 4th century, was allegedly kidnapped by pirates and taken to Ireland as a slave. Little is known about his early life except that he escaped and later returned to convert Ireland to Christianity by establishing monasteries, churches, and schools. Celebrated as the patron saint of Ireland, his feast day was primarily a religious holiday, not a celebration of Irish culture. It was not until the late 19th century when a growing sense of Irish nationalism precipitated the first St. Patrick’s Day parade in Ireland. However, the very first parade in the United States was much earlier. Irish immigrants to the United States essentially changed the religious nature of the day to a secular celebration of “Irishness,” in which all could participate. Boston held its first St. Patrick’s Day parade in 1737 and New York City in 1762. However, there is now some question whether these were the earliest parades. According to a January 21, 2022, article in IrishCentral (https://www.irishcentral.com) by Frances Mulraney, the first St. Patrick’s Day parade was in St. Augustine Florida in 1601. An expenditure log unearthed in a Spanish archive includes notes about the celebration describing St. Augustine residents parading through the city celebrating the saint. Huntington’s first St. Patrick’s Day parade was much, much later. According to the Huntingtonian it was 1935, but according to Newsday it was 1930. The first parades were organized by the Irish American Social Club which met at Finnegan’s. St. Patrick Parade, 1940. Photo by Robert Stone

|

AuthorThis blog has been written by various affiliates of the Huntington Historical Society. Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

Become a Member

Donate Today!

Signup For Our Newsletter

Thanks for signing up!

© Huntington Historical Society. All rights reserved.

The Huntington Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the Town of Huntington for its steadfast support.

The Huntington Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the Town of Huntington for its steadfast support.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed