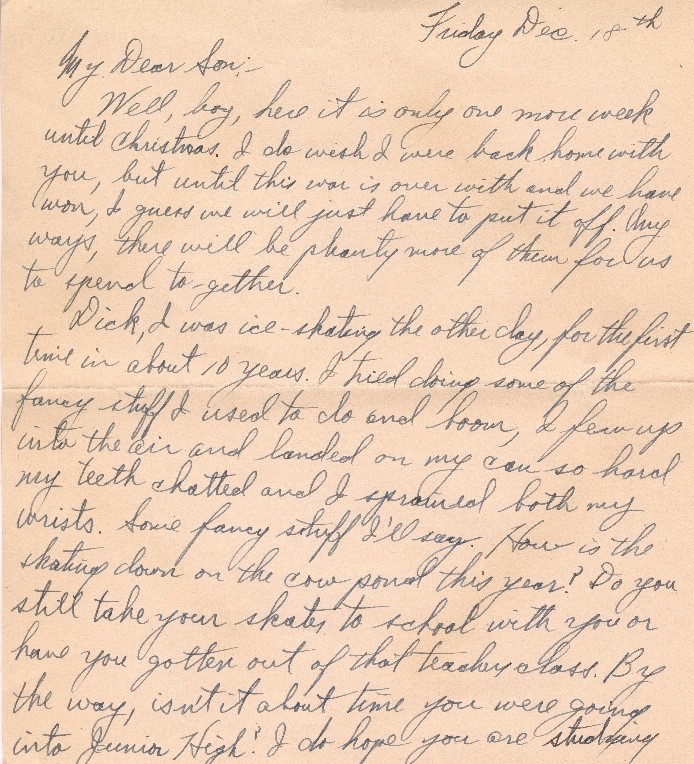

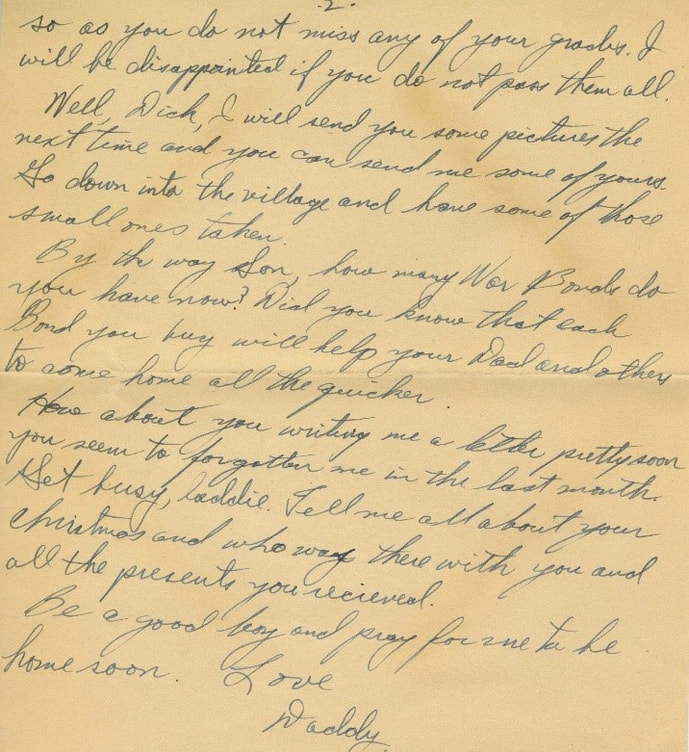

By Barbara LaMonica Assistant Archivist I remember when I was a child my mother would sit me down and insist I write thank you notes for all the holiday gifts I received from my aunts and uncles. Her reasoning was that by taking the time to write a personalized handwritten note on special stationery was a sign of respect and gratefulness. I wonder what my mother would think of today’s instantaneous emails or texts? Well she would be happy to know that letter writing is beginning to make a comeback. And it is not only older people. Millennials are the largest group to buy notecards, and Pen Pal Clubs are springing up everywhere. The LA Pen Pal club meets once a month to create their own stationery and sit down together to write letters. What exactly is the growing appeal of sending and/or receiving a letter rather than an email? One reason is that a letter is unique and tangible. To receive a letter makes the recipient feel important knowing that the sender took the time to write, choose stationery, purchase postage and mail. And the recipient is happy to receive a letter that is not a bill! Reading a letter is easier than scrolling down on a screen. Furthermore, people tend to hold onto letters for a longer period of time rather than an email which is often quickly deleted. More importantly writing, whether letters, notes, or diaries, tends to slow things down in our age of instantaneous digital communication fostering shorter and shorter attention spans. Additionally, recent research seems to verify that the physical act of handwriting has several benefits over keyboard tapping. The most important advantages are improved memory, spelling, and cognition. A 2014 study published in Psychological Science “The Pen is Mightier than the Keyboard” by P.A. Mueller and D.M. Oppenheimer compared college students who took notes on laptops vs those who used longhand. The results clearly showed that the students who had written had better retention and test scores. “The present research suggests that even when laptops are used solely to take notes, they may still be impairing learning because their use results in shallow processing.” Most importantly what is the significance of letter and journal writing for historians and archivists? In the past people wrote a great deal of letters and kept diaries. It was an integral part of life and social relations. An etiquette book from the 1890s devotes several chapters on the proper way to write letters for all occasions. “Write letters to relatives and friends very often…the longer you make them the better. The absent husband should write a letter at least once a week. Some husbands make it a rule to write a brief letter home at the close of a day.” (Hills Manual of Social and Business Forms by Thos. H. Hill, Hill Standard Book Company Chicago, 1891.pg. 105). Personal correspondences often survive for decades as keepsakes for succeeding generations. Will a substantial number of emails and texts from our age survive? How will future historians view us when most of our correspondence is digital and temporary in nature? And unlike official documents, personal writings are heartfelt expressions giving historians a perspective on the everyday life and social conventions of an era. The special collections in the Huntington Historical Society Archives contains the letters and diaries of several Huntington residents including past doctors, lawyers, homemakers and soldiers from various conflicts. Below is a letter that is part of a WWII collection written by a soldier, Chester R. Koons, to his son Richard. Unfortunately, the father was killed in 1944. The son kept the letters all his life. Below is an excerpt from a letter dated March 17th 1867 from John B. Scudder to Nettie White.

0 Comments

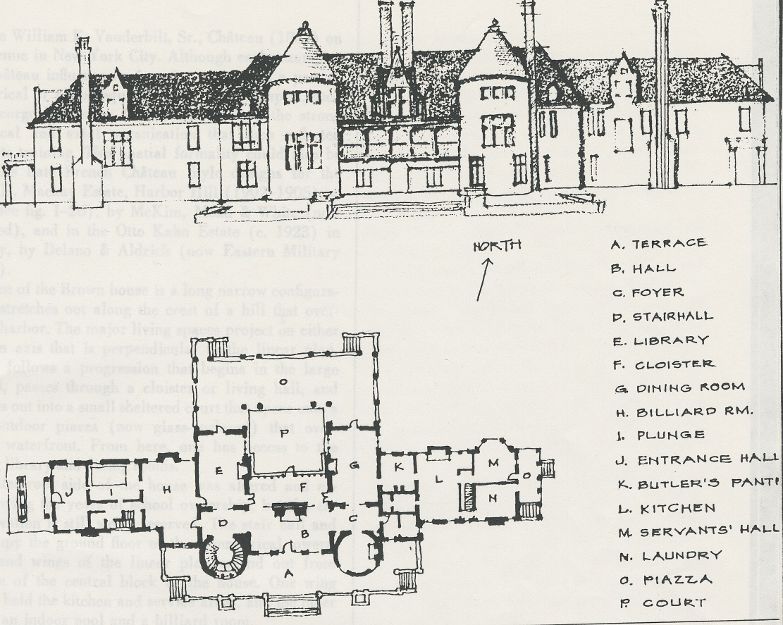

By Barbara LaMonica Assistant Archivist The George McKesson Brown Estate, aka Coindre Hall is an example of a Gold Coast mansion built around the turn of the century as a summer residence for wealthy entrepreneurs. Coindre Hall’s history is similar to that of other mansions of its time. Built during an era of great opulence, the estates eventually became untenable due to economic changes and increased taxation. Eventually the mansions and lands were sold off piece by piece by owners and descendants due to unaffordability and disinterest. Many were sold off to developers and torn down, others became public buildings or museums. Many languish as a tug of war between various community factions with differing agendas for their use. George McKesson Brown, heir to the McKesson Pharmaceutical Company fortune, purchased 135 waterfront acres facing Huntington Harbor. In approximately 1906 Brown commissioned architect Clarence Summer Luce to design a mansion inspired by chateaus he had seen while on vacation with his wife in the Loire Valley. The French Chateau style in architecture became popular in the United States around the late 19th century. This style reflected 16th century French chateaus with gabled roofs, conical towers, spires and arched entryways. Completed in 1912, the estate was known as West Neck Farm. It was essentially a self-contained manor with cows, chickens, pigs and bees as well as vegetable gardens. The out buildings, such as the garage and chauffeur’s quarters (now Unitarian Fellowship), the boat house, and the water tower were designed to reflect the style of the main mansion. At first a summer residence, West Neck Farm became a full time residence for the Browns by 1917. However, when Brown became financially strapped after losing much of his fortune after the 1929 stock market crash, he began selling off parcels of the estate’s land. In 1939 he moved into the farmhouse and sold the main house and 33 acres to the Brothers of the Sacred Heart who established a boarding school for boys. West Neck Farm was renamed Coindre Hall in honor of the founder of the religious order and the school remained open until 1971. In 1962 the former garage and chauffeur’s quarters, farmhouse and watertower was sold to the Unitarian Fellowship. In 1964 Brown died with no heirs and since then the fate of the estate has been debated.

In 1972 the Suffolk County Legislature voted to purchase the property for $750,000 with the intention of creating a harbor front park. The main mansion was leased to the Town of Huntington and continued to be used as a recreation and cultural center. In 1976 the county closed the park due to expensive upkeep. In 1981 the mansion was leased to Eagle Hill School, a school for students with learning disabilities, but by 1989 the school was struggling and had to close. Among proposals for the mansion were an expansion of Heckscher Museum, a repository for County records, a Gold Coast Museum. In 1980 the boathouse became the home of the Sagamore Rowing Club. During its tenure the rowing club put $73,000 to improve the safety of the boathouse but 70 percent of the building was eventually condemned forcing the rowing club to vacate. In 1985 the estate was listed on the National and New York State Register of Historic Places and in 1988 placed in the Suffolk County Historic Trust. It was given local landmark status by the Town of Huntington in 1990. In that same year Rep. Rick Lazio proposed the property be sold through a public referendum. In response to this the Alliance for the for the Preservation of Coindre Hall was founded with the goals of protecting, restoring and preserving the entire property. The Alliance fought off several attempt by the Legislature to sell the property. Today the mansion, which has undergone some restoration, now functions as a catering venue operated by Lessings. In 2020 the Suffolk County Legislature created an Advisory Board to oversee the rehabilitation of the property including the boathouse, the pier and the seawall. In 2023 the boathouse was put on the list of Endangered Places by Preservation Long Island. However, some residents are concerned that the park’s wetlands will be compromised by the planned renovations. The task ahead is to create a strategy that will include concerns for the natural environment as well as the preservation of an important historical legacy. By Barbara LaMonica Assistant Archivist From Gilded Age castle, to sanitation union resort, to Merchant Marine training center, to military academy, and finally restored to its original grandeur as a luxury hotel, Oheka castle has a varied and controversial history. Completed in 1919, Oheka was built by investment banker and patron of the arts Otto Kahn. The chateau style mansion was intended as a summer home for his family while they were not in residence at their 80-room Italian Renaissance style mansion in New York City. Kahn’s previous country home, Cedar Court in Morristown, NJ was gifted to him and his wife Addie Wolfe by her father. However, after about 10 years the home burnt down, and Kahn, who had been denied membership in country clubs in Morristown because of his Jewish background, eventually decided to relocate. He bought 443 acres in Cold Spring Harbor where he intended to build a chateau style country home. Desiring to have an overview of the surrounding area, Kahn had a hill built before construction on the home began. It took two years to complete the man-made elevation which made the property the highest point on Long Island. Kahn engaged famed architects Delano and Aldrich to build the French chateau inspired home. Of utmost importance to him was that the home be fireproof, the result being that the Delano- Aldrich design in steel and concrete made it the first totally fireproof residential building.

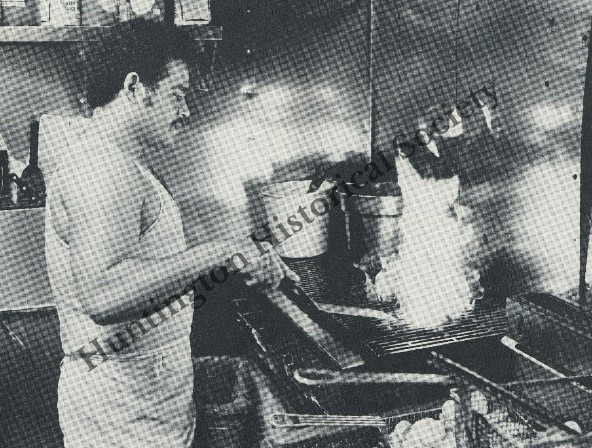

Upon completion the 112,895 square foot castle had 127 rooms, 39 fireplaces, and employed 126 full time servants. It was the second largest home in the US, second to Vanderbilt’s Biltmore in Ashville, NC. Otto Kahn was born in Mannheim Germany in 1867. His father had eight children and had a career plan for each one. In spite of Otto’s desire to become a musician, his father placed him in a bank as a junior clerk. He eventually moved to London where he became second in command at Deutsche Bank. In 1893, he moved to the United States where he joined Kuhn, Loeb & Co. He became a partner with railroad builder E. H. Harriman in the task of restructuring the Union Pacific Railroad. Kahn gained a reputation as one of the most skillful reorganizers of railroads. He went on to restructure the Baltimore and Ohio, the Chicago and Eastern Illinois and other systems. In international finance, he negotiated for opening the Paris Bourse to American securities. A philanthropist and patron of the arts, Kahn was a stockholder and founding member of the Metropolitan Opera Company, and was a collector of paintings, tapestries, and sculptures. He authored several books on varied topics including art, history, and business. A few years after Kahn died in 1934 his wife Addie sold the castle for a mere $100,000 to the Welfare Fund of the Sanitation Workers of New York (Sanita). Oheka, renamed Sanita Lodge, was transformed into a country retreat for low paid department employees to vacation with their families. Addie, a patroness of the Women’s Trade Union League, stated she was pleased that the property could now be used to benefit so many. However, others in the area were not so pleased. The idea that “street sweepers” would use the luxurious surroundings triggered ethnic and class discriminations lurking beneath the surface. The Long Islander, a fierce opponent, ran an editorial on June 9, 1939 that read “…the finest land in Huntington is to be placed in the lowest category…the value of the parcels in the neighborhood will be correspondingly lowered.”

Because the lodge now consisted of a Horn and Hardart cafeteria, a cigar stand and a switchboard, Sanita should be considered a boarding house or hotel, not a strictly a residential building. Furthermore, the union did not get a Certificate of Occupancy. Because the union was a not-for-profit, local residents feared tax exemption would shift the tax burden onto them.

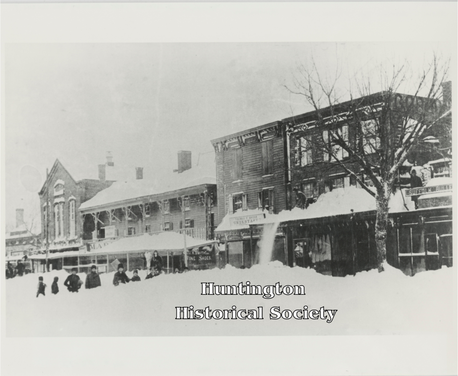

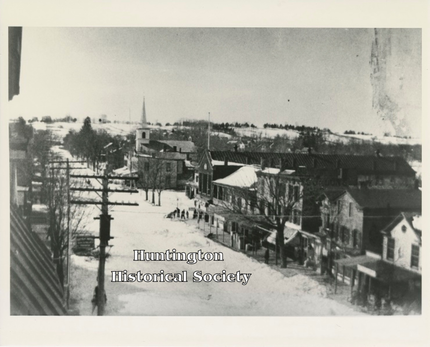

However, Sanita had many supporters among Huntington businessmen and residents. During a period of high unemployment and business depression, Sanita provided somewhat of a solution. The lodge hired local people as construction and service workers. Additionally, the lodge bought supplies from local businesses, and sanitation vacationers shopped in town. The Huntington Businessmen Association started a petition in favor of keeping Sanita open. The first petition had over 1400 signatures. By this time Mayor LaGuardia got involved and offered to act as a mediator. He set up a meeting between the town board and Sanita. He proposed that the Sanitation Union would be willing to pay partial taxes on the property. But the board held firm. It refused a certificate of occupancy and refused tax exemption. “I would not want to be as dead as this proposal” claimed LaGuardia. In the meantime, the union said it would no longer pursue legal means. “We do not want to be somewhere where we are not wanted,” Sanitation Director Carey stated. As of April 1940 the Sanita cause was defeated. Eventually the Sanitation Union, with the support of Franklin Roosevelt, did find suitable property upstate. The property reverted to the Kahn family and almost immediately was subdivided and bought by a local developer. The town approved rezoning to 1/3-1/4 acre plots for the construction of homes. In 1942 the Merchant Marine requisitioned the abandoned mansion and Oheka became a radio operator school through 1945. In 1948 Eastern Military Academy purchased it and ran a boarding school until 1979. For the next four years Oheka fell into ruin. In 1984 developer Gary Melius purchased the home and began restoration. Today, restored to its Gilded Age opulence, Oheka Castle is a luxury hotel and event venue. By Barbara LaMonica Assistant Archivist Notwithstanding the occasional snowstorm, winters have been getting warmer and wetter. In the past winters had more frequent single digit temperatures and several snowstorms a season. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported for the 2022-2023 season the average temperature was 2.7 degrees above average, and the precipitation average made it the third wettest winter on record. The east coast had one of the least snowy seasons, but plenty of rain. In addition to the famous March snowstorm of 1888, the Great Christmas Blizzard of 1947, the blizzards of Feb 2006, and January 2016 a sampling of Huntington’s previous winters as recorded in the Long Islander illustrates the contrast between past and present weather. Although greatly inconvenienced by the storms the populace often took joy in the fact that the conditions afforded great sleigh riding. Main Street in Huntington after the blizzard of 1888 1839- It snowed for three days rendering all roads impassable, but “We now have fine sleighing and our citizens both old and young are proving by actual demonstration the country sleigh rides in winter are nothing to sneeze at!” (Long Islander 12/27/1839.) 1853-A large snowstorm completely stopped the Long Island Railroad for five days. However “The beautiful sleighing has been well improved by our citizens...the streets are filled with fine teams, handsome sleds filled with gay flowing robes and jingle bells. A party of eighteen sleds from this village and Cold Spring Harbor made a visit to Hempstead on Tuesday.” (Long Islander 1/21/1853) 1865-Extremely cold weather, temperature hovers around zero with very little variation since December. The sound was frozen over “...as far as can be seen from the necks.” Long Islander 2/17/1865 1866-temperatures ranging from ten to thirteen below zero for consecutive days, and fourteen and fifteen below in New York City and Brooklyn. “...almost everyone was willing to admit that it was cold, and if they were not, their frozen ears and noses attested to it.” (Long Islander 1/12/1866) 1896-The long Islander reported an unusual snowstorm in May. Due to the raging snowstorm, a schooner was driven onto Little Reef to the east of the Eaton’s Neck Lighthouse. “The waters of the sound were lashed into a fury by the gale and four of the five men on the vessel, fearing she would go to pieces, launched the yawl boat...the boat was swamped and two of the men drowned. The fall of snow was followed by a storm of sleet afforded an unexpected opportunity for sleigh riding.” 1936- Long Islander reported that Huntington Harbor was completely covered in ice from shore to shore, the thickness approaching 16 inches. (Long Islander 2/21/1936. In light of the recent earthquake in Queens and on Roosevelt Island, a slight digression. In August 1884, an earthquake hit Long Island. According to the Long Islander, the shock was felt in Washington D.C., Canada, Ohio and the Atlantic Coast. “Crockery and glassware were shaken on tables...doorbells in several houses in our village rang violently...Some clocks were stopped... and chairs were moved with persons in them...one lady Mrs. Pettit eighty –two years of age was rolled from here bed. Several persons fainted and sick people were very much affected. ...the death of Mrs. Almed Tillot was very much hastened by the shock as she was suffering from a nervous affliction...others were greatly affected in their heads.” (Long Islander 8/15.1884) Main Street in Huntington covered with snow, year unknown

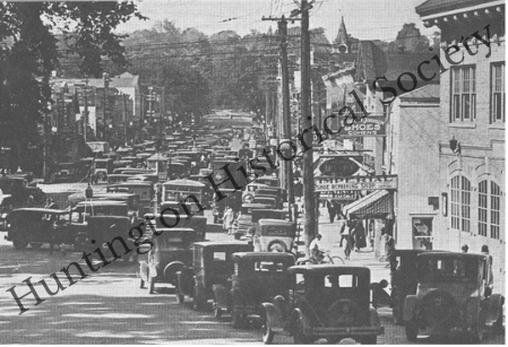

By Barbara LaMonica Assistant Archivist It might be fun to look at some articles from The Long Islander over December-January long ago. It is fun to see the topics that concerned the editors from roughly the 1840s through the 1930s. You will find that some of these issues are still around today! Hint-traffic congestion and parking for instance. Complaints about town parking In the December 3, 1920 issue, complaints were made about parking cars on the sides of New York Avenue between Main Street and Elm Street in spite of a Town Ordinance prohibiting the practice. “The congestion is so great at times that it is with great difficulty a car going in either direction can get through. It is worse since the trolley cars have been running. It is at times impossible for a person wishing to get mail to the Post Office without alighting a block away.” It was suggested that cars be parked diagonally to the curb with no parking on the east side. In addition, a yard should be put aside for the care of the cars for hours at a time at a moderate fee. Seems like congestion and parking have always been a problem! We are a healthy locality December 25, 1885. Article claiming Long Islanders in general and Huntington residents in particular are a healthy lot reaching advanced age. “...Thomas Scudder, 87 recently remodeled his house at the Harbor with the hopes of living many more years...Mr. Isaac Titus, aged 88, was one of them who did his share of farm work during the past season. His memory is very good and a chat with him concerning events of the War of 1812 is very interesting. Jonathan Jarvis is 84 and can been seen about our streets everyday taking great interest in the passing events...P.C. Jarvis his brother who sailed many a sloop between this harbor and New York is an octogenarian and his mind is clear...There are numerous others we might include in this article but we mention the above as proof of the healing locality we live in.” A few of Huntington's Spry Elders Too many escapees January 10, 1913 article reported that the number of escapees from the Suffolk County Jail was the subject of a Grand Jury investigation. Apparently, the escape of the notorious thief and confidence woman, Esther Harris, ignited the crisis. Esther entranced her jailers who allowed her all sorts of supplies and gourmet treats from the outside as well as holding bridge whist parties in her cell. She also ran a jewelry business within her confines. “...Esther who could acquire in a clandestine way an average of a thousand dollars’ worth of jewelry and silverware in a month.... Among her assets was a gold watch...which she let the wife of the jailer have for $20 throwing in a ring for the daughter for good measure." Eventually outside friends provided Esther with a car ride to the local train station before daylight. Other inmates included Peter Musso who ran a barbershop in the jail and made a tidy sum shaving outsiders, with as the article continued, no rent to pay and razors furnished by the county. As a remedial measure, the article suggested that prisoners should no longer have the keys to their own cells and corridors! “The taxpayers of Suffolk County should feel highly gratified that they built such a handsome and comfortable boarding house for their prisoners, and it is said to be so safe that it would take an experience burglar to break in-few ever care to get out.” Shop Local On December 8, 1911 The Long Islander urged Huntington residents to do their shopping local. “Nearly all the local stores have laid in large stocks of useful and ornamental Christmas goods, which you can buy just as cheap as to go to city stores...Remember that the businessman hereabouts pays his part toward supporting the village and town government. He is at your service every day in the year. Do not forget him at Christmas.” Huntington Village continued to be a bustling shopping spot. Highway Robbery

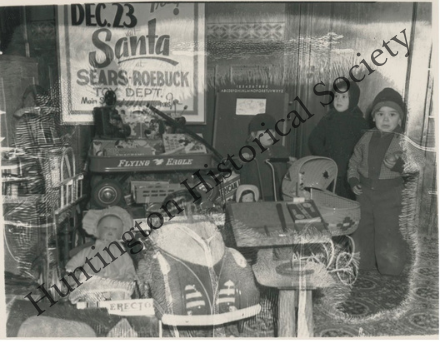

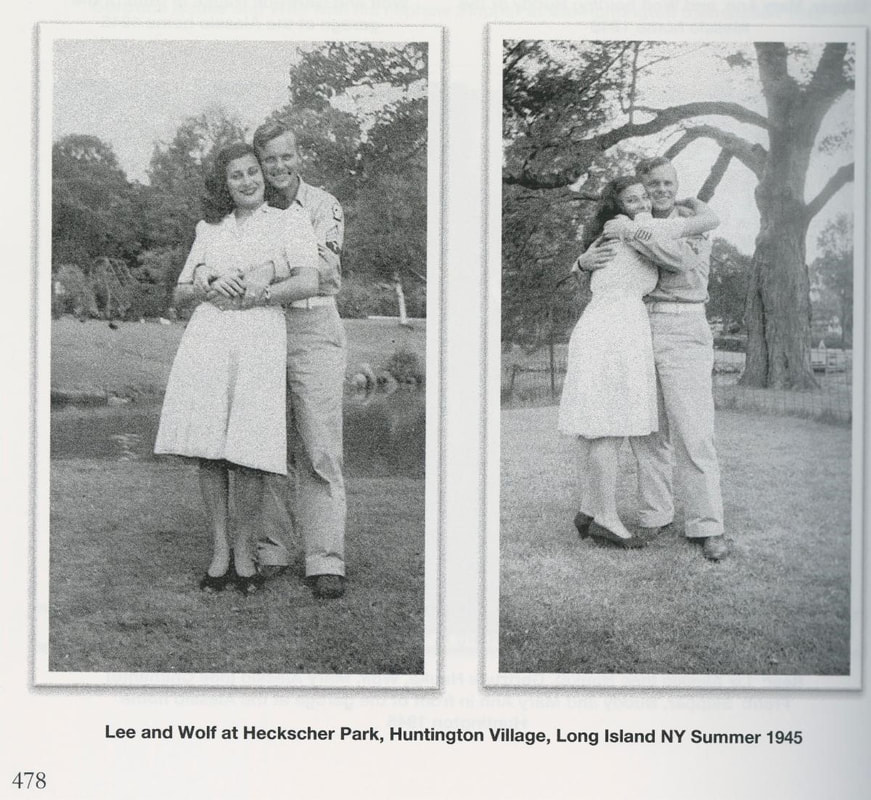

December 10, 1920. Article on a crime wave that hit busses running between Melville and Huntington Station. “The hold-up of the bus....by a couple of highway men, and the robbery of the passengers, smacks of the terrors of travel in the Far West when Ben Halliday ran stage coaches from the railroad terminals in Missouri and over the Rocky Mountains to California.” The article speculates that drivers and passengers may have to be armed unless the “carnival of crime” is stopped by an effort of all the police forces of county, state, national levels cooperate to end this crime wave. Merry Christmas December 1, 1938. There is a long tradition of holiday parades in Huntington. This article reports on plans for Christmas parade with several cartoon characters popular at the time. Thousands of children will be on hand to welcome Santa Claus and his court when they arrive from in their special auto trailer from the North Pole...Popeye, no less, will be the grand marshal of the parade and the flower- smelling, peace-loving Ferdinand the Bull will also be a member of Santa’s court, as will Mickey Mouse, Eskimo Eddie, Patrick Penguin, Polar Bear Pete and the seven dwarfs, not forgetting Dopey” By Barbara LaMonica Assistant Archivist  Commack Cemetery If you are fascinated by cemeteries and love to spend time reading tombstone inscriptions, looking for the graves of famous people, or simply enjoying the verdant and peaceful surroundings of park-like burial grounds then you qualify as a true taphophillac (Taphophilla -ancient Greek taphos, funeral rites, burial, philia, love). Genealogists, historians, and photographers are drawn to cemeteries for various reasons. Both professional and amateur historians go to cemeteries for the information they can reveal about a town’s history. For example, family names which coincide with names of local streets indicate those families were prominent in the community. In the earliest burial sites, which were often in churchyards, the areas closest to the church, or those facing east were reserved for the more important citizens. Death rates and infant mortality can be measured. Large groupings of death dates can indicate an epidemic or other natural catastrophe. Genealogists can find previously unknown ancestors as family members were often buried next to each other or in mausoleums. Birth and death dates can be compared to written records. Because the census comes out only every ten years, tombstones may be the only record for a child who was born and died within that period. Many cemeteries have ornate sculptures and elaborate mausoleums considered artistic architecture, which attracts photographers. Older weathered tombstones have interesting textures and contrast creating pleasing images. Park like cemeteries provide lush landscapes as well as being habitats for wildlife. Burial grounds and grave markers have changed over the years. In early colonial America, burial grounds were mainly in churchyards or in the center of a village, preferably on a hill. In keeping with strict puritan tradition, grave markers were plain usually made of fieldstone or wooden planks, with only the name and date of death. Eventually sandstone and slate were used, etched with simple verse or something about the person’s life. Images of crossbones and skulls were prevalent as reminders of mortality. Later on, more positive images of winged cherubs emphasizing the afterlife became popular. As churchyards became overcrowded and real estate values rose, rural cemeteries were established on the outskirts of towns and cities. Not being associated with a particular church, many of these were public and non-denominational. This led to more landscaped cemeteries that were garden- like. With winding paths, benches, and shade trees, cemeteries were now conducive for family outings and even picnicking. Founded in 1831 Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts was the first rural cemetery in American. Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn followed shortly after in 1838. There are many historic cemeteries within the Town of Huntington for one to explore. Four in particular are within the the village area. The Old Burial Ground- Located at 228 Main Street, the Old Burial Ground was founded in the 17th century and in 1981 was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. It is the former location of an English revolutionary fort. After the American Revolution, the fort was dismantled and the burial grounds restored. There one can find graves of Revolutionary and Civil War veterans. By Barbara LaMonica Assistant Archivist When former Huntington resident Daniel Thomas Nauke discovered boxes of forgotten letters written between his parents during WWII, he brought the letters home and put them on a shelf. It took the COVID lockdown years later to prompt Daniel to finally read and organize the letters. He found they revealed not only a love story between his parents but also a story of immigrant families, a neighborhood, and life during WWII.

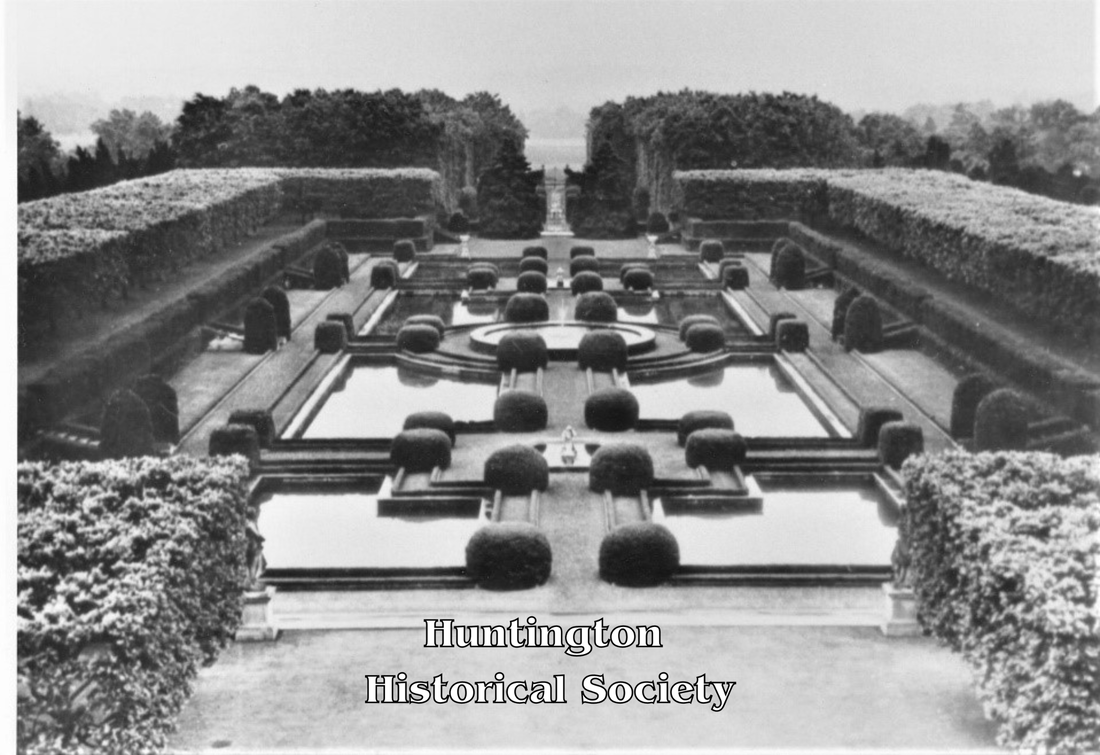

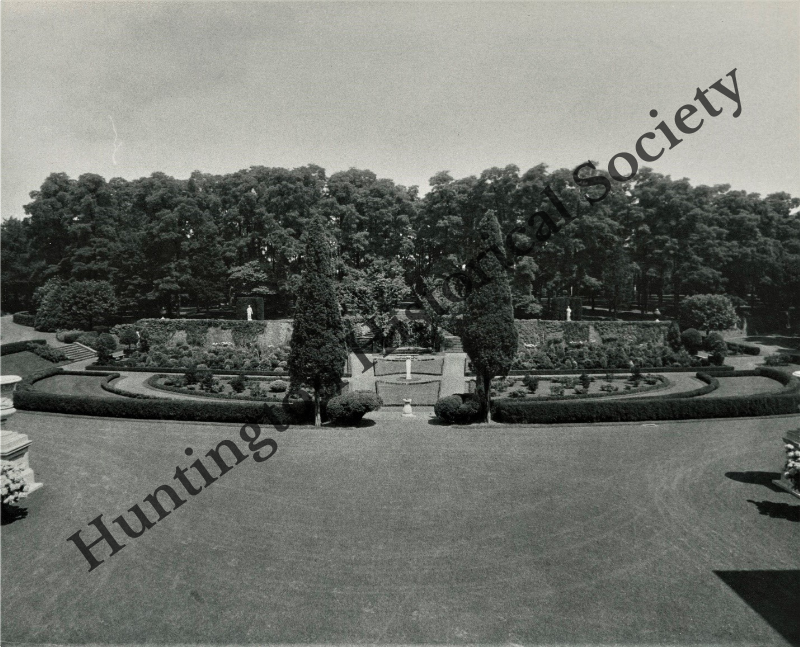

Using the letters as a springboard, Daniel began a research project involving old maps, censuses, and newspaper articles to recreate the time frame of the neighborhood and the families that lived there. The project evolved into the book Always Faithful Letters Between An American Soldier and His Hometown Sweetheart During WWII. The result of this research is a work that is not only a personal love story, but also an historical document of the times in Huntington Station. By the 1920s, the streets in Huntington Station had been laid out, building lots were being sold and homes built. Immigrants came to this area and eventually settled in the new community, creating a diverse neighborhood of Germans, Irish, Italian, and Polish families to name a few. This is where the author’s parents, Lee Alessio and Wolfgang Nauke, grew up across the street from each other on East 4th Street and Fairground Avenue. Lee was the daughter of Salvatore Alessio from Acri Italy, and Wolfgang immigrated with his parents from Dresden, Germany in 1923. Interspersed with the letters, the author provides photographs, maps, postcards, and WWII memorabilia, as well as an extensive index of families and businesses that populated the area. This book illustrates that old family documents can be more than personal memories, they can provide historical insight of interest to everyone. If you are interested in purchasing this book when it becomes available, please contact [email protected]. By Barbara LaMonicaAssistant Archivist The period from roughly 1877 to the early 20th century demarks the era known as the “Gilded Age.” The term Gilded Age was first coined by Mark Twain who, in his usual ironic fashion, used the word gilded to denote something that was shiny on the surface, but corrupt underneath. The Gilded Age coincided with a period of vast social and economic restructuring known as the Second Industrial Revolution. Urbanization and innovations in transportation, communication, production techniques and cheap immigrant labor opened up markets and allowed for the quick delivery of goods over vast distances. This growth in production created great wealth, but also great inequality and poverty, rendering the economic system inherently unstable, and culminating in the crash of 1929. The industrialists of this period - the railroad men, the oilmen, the steel men and the bankers -epitomized the lifestyle of the Gilded Age. Luxurious houses along Fifth Avenue were furnished with rich fabrics, marble, gold, carved ornate furniture imported from Europe and expensive antiques and art collections. Many mansions had ballrooms that hosted parties for hundreds of people. With an abundance of disposable wealth, families such as the Fricks, the Morgans, the Vanderbilts and the Coes built weekend or summer homes along the North Shore of Long Island, known as the Gold Coast. One such industrialist, Walter Jennings (1858-1933), built his estate in Lloyd Harbor. Jennings was the son of Standard Oil co-founder Oliver Burr Jennings, and was a first cousin to William, Percy and Geraldine Rockefeller. He was a director of Standard Oil New Jersey, president of the National Fuel Gas Company, director of the Bank of Manhattan, and trustee of the New York Trust Company, eventually to become Chase and Chemical Banks respectively. Beginning in 1895, Jennings began buying property in Cold Spring Harbor* (in buying 374 acres Jennings also acquired the Glenada Hotel, which he tore down). In 1898, he engaged architects Carrere & Hastings to design a Georgian mansion and the Olmstead Brothers to create the formal gardens. Carrere & Hastings had both apprenticed to Stanford White, and among their impressive achievements in Manhattan are the main branch of the New York Public Library on 5th Avenue, The Standard Oil Building, the Henry Clay Frick House and the Cunard Building. The Olmstead Brothers’ famous creations include Central Park, Bayard Cutting Arboretum, Forest Park and Prospect Park.

Jennings and his wife, Jean Brown Jennings, and their three children made Burrwood their summer residence. In retirement, Jennings moved permanently to Burrwood where he enthusiastically engaged in farming activities.

In a little over 50 years’ time, many of the Gold Coast Mansions were abandoned or torn down. The Great Depression, increased income taxes, rising land costs, high maintenance and personnel costs contributed to their demise as the cost of maintaining the estates became prohibitive. Some families lost their fortunes, or subsequent generations had less disposable income or simply found the style of the mansions not to their taste. Many estates were subdivided due to social and economic changes such as the movement to the suburbs of a growing middle class creating a demand for land to build single-family homes. Jennings died in 1933. His will stipulated that his wife could continue to live at Burrwood, while leaving the estate to his son. After Mrs. Jennings’ death, The Industrial Home for the Blind purchased the mansion and 32.5 acres for $90,000 in 1951. In 1952, it opened as a residence for the blind, but by the early 1980’s the maintenance and personnel costs became too expensive. Additionally, the resident population was decreasing due to more community support services enabling the disabled to remain in their homes or with family. After the remaining residents relocated to nursing homes or other housing programs, the property was sold in 1987 for 5.5 million to a New Rochelle developer who intended to restore the mansion to a single family home and subdivide the rest of the land to build 10 homes. However, the deal fell through and the mortgage holder seized the property. Another development company bought 10 lots and built houses. Unfortunately, there were no buyers willing to restore the house, and the Village of Lloyd Harbor had no landmark preservation ordinance in place that would have prevented destruction of the mansion. Burrwood was torn down in 1995. Property taxes at that time assessed at over $100,000 as well as 6.5 million dollars for restoration. If you still want to see a vestige of Burrwood’s opulence, you can take a stroll in the Elizabeth Street Garden in Manhattan’s Little Italy. Among various sculptures, you can sit under an Olmstead iron wrought gazebo from the Burrwood estate. *The property later became part of the Incorporated Village of Lloyd Harbor. By Barbara LaMonicaAssistant Archivist The Huntington Historical Society received a $39,000 grant from the New York State Program for the Conservation and Preservation of Library Research Materials Discretionary Grant Program to conserve and digitize 160 audio cassettes and 16 reel-to-reel tapes comprising the Society’s oral history collection. The goal of the audio preservation is to produce an accurate and intelligible reproduction of the source material and create accessible Mp3 files. The collection was sent to the Northeast Document Conservation Center in Massachusetts where a total of 244 hours of recordings were transferred, processed, and repaired. The interviews span the years from the 1950s to the 1980s, and depict through first person accounts, the transformation of Huntington from an early 20th century rural community through the urban renewal efforts of the 1960s-1970s. Included in this collection is a special project developed in conjunction with the Town of Huntington entitled “Reaching for a Dream.” The project documents the history and contributions of Huntington’s local ethnic communities. Sixty-five persons from the African-American, Italian, and Latino communities were interviewed between 1987 and 1988. The preservation of these oral history interviews insures that a significant part of Huntington’s history, told from the standpoint of local townspeople, will now be accessible to the public. Reaching for a Dream Oral History

By Barbara LaMonicaAssistant Archivist

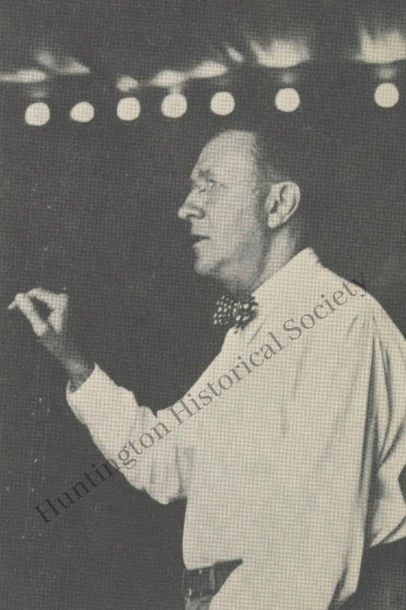

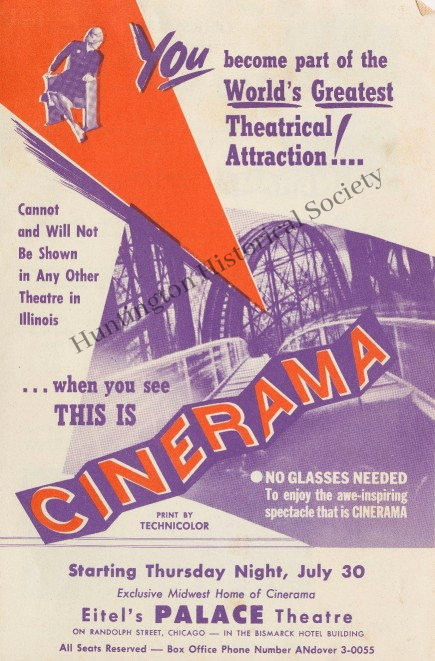

He returned to Paramount in 1929 and left in 1936 to begin work on special features for the New York World’s Fair. He created special motion pictures projected on the interior of the Perisphere, an enormous modernistic structure that served as the central theme of the fair. He built his first model for the Cinerama process but it was considered too expensive and radical at the time. During this period, he bought the Kenyon Instrument Company of Boston and relocated it to Huntington as the Kenyon Instrument Company. The new company produced nautical and aircraft instruments. During WWII, he developed the Waller Gunnery Trainer, a simulator utilizing multiple cameras projecting pictures of moving planes onto a conclave screen. This resulted in producing realistic aerial battle situations, thus showing gunners how to hit them. The U.S. Air Force, Navy and the British Admiralty used the trainer, which is credited with saving over 350,000 lives during combat.

Essentially the process Waller created called for three 35 mm cameras equipped with 27mm lenses. Each camera photographed one-third of the picture in a crisscross pattern. The film was projected from three projection booths onto a large curved screen. The process attracted Lowell Thomas who organized a corporation to further market Cinerama. Louis B. Mayer was Chairman, Thomas was Vice President and Waller was Chairman of the Board.

On September 30, 1952, This is Cinerama opened in New York City to a capacity crowd. The film opened with a breathtaking rollercoaster ride, and critics lauded the production, seeing it as an alternative to the rising popularity of television. The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm and How the West Was Won were two of the first features to be shot in Cinerama. However, it soon became obvious that the Cinerama process was too cumbersome to shoot with three cameras mounted on one crane, and the need for three projection booths with at least three projectionists added to a prohibitive cost. Most existing movie theatres could not be easily converted to accommodate the process, as the cost for this could be as high as $75,000. Eventually producers decided to shoot on 70mm film with a single camera and project onto a larger screen with a single projector. Even though the Cinerama process gradually faded out it still remains a significant contribution to cinema technology being a precursor to IMAX and Virtual Reality. |

AuthorThis blog has been written by various affiliates of the Huntington Historical Society. Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

Become a Member

Donate Today!

Signup For Our Newsletter

Thanks for signing up!

© Huntington Historical Society. All rights reserved.

The Huntington Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the Town of Huntington for its steadfast support.

The Huntington Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the Town of Huntington for its steadfast support.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed